9 Innings 9 InningsA Baseball History Reader

J. Manning, Editor

|

Issue # 4: September 5, 2006

Jackie and the Bombers ... Moriarty vs. the White Sox ... The First Professional Baseball Club ... The Greatest Triple Play ... Minnie Minoso: The Negro Leagues ... Stats: Triple Crown Winners (Pitching) ... Year in Review: 1903 ... The 1903 World Series ... Player Profile: Kirby Puckett ... Baseball Dictionary (alley-American Baseball Coaches Association)

|

"Baseball is dull only to dull minds."

-- Red Smith

1st INNING

Jackie and the Bombers

On April 2, 1931, the Yankees were barnstorming north out of spring training camp when they stopped in Chattanooga, Tennessee for an exhibition game against the Southern Association's Lookouts. Chattanooga righthander Clyde Barfoot, formerly of the Cardinals and Tigers, started against the Bombers. New York outfielder Earle Combs led off with a double, and shortstop Lyn Lary followed with a run-scoring single. Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig were scheduled to follow. On April 2, 1931, the Yankees were barnstorming north out of spring training camp when they stopped in Chattanooga, Tennessee for an exhibition game against the Southern Association's Lookouts. Chattanooga righthander Clyde Barfoot, formerly of the Cardinals and Tigers, started against the Bombers. New York outfielder Earle Combs led off with a double, and shortstop Lyn Lary followed with a run-scoring single. Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig were scheduled to follow.Lookout manager Bert Niehoff strolled to the mound and signaled for a new pitcher. From the bullpen area in front of the right-field bleachers trotted a reliever: Jackie Mitchell, seventeen years old, a left-hander, and a girl.

The crowd of about four thousand cheered Mitchell as the Bambino stepped in to bat against the bambina. Ruth swung hard at the first pitch and missed. He swung harder at the second pitch and missed again. Ruth stepped out and demanded the home plate umpire examine the ball. The Babe stepped back in, watched the next pitch sail across the plate for called strike three, tossed his bat away in disgust, and stomped back to the dugout.

Gehrig followed and missed three straight pitches. Second baseman Tony Lazzeri tried to bunt Mitchell's first pitch but missed, then took four straight balls for a walk. Done for the day, Mitchell trotted off the mound to a hearty ovation.

Later accounts claimed the girl's appearance and the strikeouts were well-orchestrated publicity stunts, but folks were still impressed.

-- David Cataneo

Baseball Legends and Lore

[IMAGE: Jackie with Ruth and Gehrig]

2nd INNING

Moriarty vs. the White Sox

(May 30, 1932) In the most violent clash between an umpire and players in modern baseball history, George Moriarty duked it out with four pugnacious members of the Chicago White Sox. (May 30, 1932) In the most violent clash between an umpire and players in modern baseball history, George Moriarty duked it out with four pugnacious members of the Chicago White Sox.It was a split decision.

Tempers were frayed throughout the Memorial Day doubleheader in Cleveland as the White Sox questioned Moriarty's eyesight and ancestry much of the afternoon. It reached a feverish pitch in the bottom of the ninth inning of the second game, with the White Sox ahead 11-9.

The Indians rallied and had the winning runs on base when Milt Gaston fired a 2-2 pitch to Earl Averill. Gaston thought it was strike three but Moriarty, umpiring behind the plate, called ball three. Averill belted the next pitch for a game-winning triple.

As the ump headed for the dressing room, the White Sox heckled and cursed him. Fearing for his safety, several Indians crowded around Moriarty and urged him to hurry before trouble broke out. "Don't try to rush me, boys. I'm not afraid of what these fellows will do," said the hard-as-nails, six-foot, 200-pound arbiter.

In a runway leading to the clubhouse, Chicago catcher Charlie Berry, a former football All-American, challenged the umpire to a fight. "I'll take on the whole White Sox club!" bellowed Moriarty. "I'll fight all of you one at a time."

Gaston threw down his glove and stepped forward. "You might as well start with me." So Moriarty did. He floored the pitcher with a solid right to the jaw.

White Sox manager Lew Fonseca, Berry, and another catcher, Frank Grube, also a former college football star, then piled onto the 47-year-old umpire. As Moriarty tumbled to the floor, the White Sox pummeled him and kicked him in the head. Several Indians tried to pull them off him, but Moriarty was so tough that he still got in his licks and shouted at his rescuers, "Don't interfere!" But they did anyway.

Moriarty was taken to the hospital and treated for a broken hand (from knocking out Gaston), spike wounds to his head, and bruises to his face.

Fonseca immediately claimed that Moriarty went out of his way to invite trouble: "The tipoff is that he left the field through the players' runway toward the clubhouse instead of going into the umpire's dressing room by the usual route. He spent the afternoon begging for trouble -- and he finally got it."

American League president Will Harridge scoffed at Fonseca's weak excuse, fined all four White Sox, and suspended Gaston for 10 days.

It was the only time that Moriarty was the loser in a brawl -- and it had taken three opponents to get him down. The White Sox had forgotten what a bruiser he was. Once, during his days as a third baseman for the Detroit Tigers, he had argued with the mean, feared Ty Cobb. As they readied for fisticuffs, Moriarty handed Cobb a bat and said, "This makes it even." Then he proceeded to beat the pit out of the Georgia Peach.

-- Bruce Nash & Allan Zullo

The Baseball Hall of Shame 2

3rd INNING 3rd INNINGThe First Professional Baseball Club

Baseball has it own version of the Wright brothers. By the end of the Civil War, baseball's Wrights, Harry and George, sons of a famous British cricketer, could often be found on the Elysian Fields. In 1865, Harry left New York to take a $1,200-a-year job as an instructor at the Union Cricket Club in Cincinnati. The next year he formed the first professional baseball club, the Red Stockings, recruiting for his lineup some of the best players in the land, including his brother George, a shortstop. Here is the roster of the first professional team, together with the players' occupations and salaries:

Asa Brainard (P), insurance, $1,100 ... Doug Allison (1B), marblecutter, $800 ... Charles Gould (2B), bookkeeper, $800 ... George Wright (SS), engraver, $1,400 ... Fred Waterman (3B), insurance, $1,000 ... Andrew Leonard (LF), hatter, $800 ... Harry Wright (CF), jeweler, $1,200 ... Cal McVey (RF), piano maker, $800.

Harry Wright was a pretty good player: He once hit seven home runs in a game, and as a pitcher he supposedly threw the first changeup. But his true genius was as an organizer and a manager of men. In 1869 he put the Red Stockings on the road, traveling 11,877 miles and drawing some 200,000 spectators. The team would go on to win 91 consecutive games, a string that was frayed only by a tie with a team from Troy, N.Y., and broken in Brooklyn in June of 1870.

....Harry, borrowing an idea from the theatre, kept a "property bouquet" around, which he would present to any of his players who had performed especially well. The ceremony became so common, however, that his players started turning down his flowers.

Still and all, Harry Wright was much beloved, and as early as 1874, he was being called "the father of the game." He managed every year until 1893, when he retired to become the chief of umpires. He died at the age of sixty in 1895 and was given a huge funeral in Philadelphia. One of the floral arrangements spelled out "Safe At Home."

George Wright was the game's first great shortstop. In 1869 with the Red Stockings, he scored 339 runs in 57 games, with 49 homers and a .629 batting average. He was one of the dominant hitters in the National Association, the first professional league, but his skills began to diminish after the National League came into being in 1876. He managed only one season, in Providence in 1879, and beat his brother Harry's Boston club by five games to win the pennant. He remains the lone major league manager to have won a pennant in his only season.

In the 1890s, George Wright came away from a baseball game sneering, "Imagine, players wearing gloves. We didn't need them in our day." George, however, made a nice living by selling baseball gloves through his early sporting goods conglomerate, Wright & Ditson, until he was ninety. His last contribution to baseball was of a dubious nature, however. He was a member of the Mills Commission which credited Adner Doubleday with the invention of baseball. He should have known better, having trod the same turf as Cartwright. Unfortunately George never attended any of the commission meetings.

The game in which the Red Stockings' 91-game undefeated streak ended took place at the Capitoline grounds in Brooklyn against the Atlantics on June 14, 1870. As it turned out, it was baseball's first truly great game. While 12,000 fans tried to squeeze into a park built for 5,000, the Cincinnati club took a 2-0 lead in the first inning, justifying the pre-game odds of 5 to 1. But then a pitchers' duel between Brainard of the Red Stockings and George (The Charmer) Zettlein of the Atlantics developed, and at the end of nine innings the score was tied at 5-5 (a very low total for the era). Brooklyn considered this a moral victory. But, as the crowd spilled out onto the field and the Atlantics hugged each other, Harry Wright and the Brooklyn captain, Bob Ferguson, called upon Henry Chadwick. "The game should be resumed and continued until one team scores sufficient runs to win the game," the great man intoned.;

So the field was cleared of spectators, and the game resumed. The Red Stockings failed to score in the top of the tenth, and the Atlantics might have scored in their half of the inning but for some gamesmanship by George Wright. With runners on first and second and one out, the Atlantics batter hit a soft popup to the shortstop. Wright cupped his hands as if to catch the ball, but let it trickle through his hands to the ground. He then tossed to Waterman at third for the force, and Waterman threw to Sweasy at second for a double play. This trick later gave birth to the infield fly rule; but for the time being, the fans were furious with rage. According to one account, "George was the victim of every name on the rooter's calendar ... but through the atmospheric blue streaks, his white teeth gleamed and glistened in provoking amiability." Cincinnati scored two runs in the top of the twelfth, and as the sun began to set, so did the hopes of Brooklyn. Fans began to leave to beat the rush.

Then Charlie Smith led off for the Atlantics with a single and went to third on a wild pitch. The next batter, Joe Start, hit a long ball to right field that landed on the fringes of the crowd. When McVey attempted to pick it up, a Brooklyn fan climbed on his back. By the time he threw the fan off his back and returned the ball to the infield, Smith had scored and Start was standing at third.

The next batter was out, and then Ferguson, a right-handed hitter, surprised the Red Stockings by taking a left-handed stance. The captain wanted to avoid hitting the ball toward George Wright, and thus became the first recorded switch-hitter. He ripped the ball through the right side of the infield to tie the score, and the crowd went wild. Bothered by either the crowd or the gathering dusk, first baseman Gould bobbled a grounder, threw wide of second in an attempt to get Ferguson, and watched in despair as the Atlantics captain came all the way around to score. Brooklyn won 8-7, and Cincinnati's 91-game unbeaten streak was over.

The Atlantics had a number of players of note in their lineup against Cincinnati. "Charmer" Zettlein, an ex-sailor who had served under Admiral Farragut, was the hardest thrower of his day. Despite his nickname, Zettlein was not able to talk his way out of a case of mistaken identity during the Chicago Fire of 1871, when a mob took him for a looter and beat him severely. He still went on to win 125 games in the five years of the National Association.

Brooklyn's shortstop was the diminutive, five-foot-three Dickey Pearce. Pearce, for one thing, invented the bunt. For another, he was the first shortstop actually to position himself between second and third; until Pearce came along, shortstops inhabited the shallow outfield.

The second baseman for the Atlantics was Lipman Pike, the first great Jewish ballplayer. Pike, in fact, appeared in his first boxscore in 1858, one week after his Bar Mitzvah. He and his brother Boaz played for the Atlantics after the Civil War, but in 1866 the Philadelphia Athletics offered him $20 a week to play third base. By 1870 he was back with Brooklyn, and he played and managed another seventeen years until he retired from baseball at forty-two to go into the haberdashery business. Pike once ran a race against a standardbred horse named Charlie for $200 -- and won. The 100-yard race went off on August 27, 1873: The horse was allowed to start 25 yards behind the line, and Pike took off when the horse reached him. They were neck-and-neck for most of the race, and when Pike began to pull away, the horse broke stride and began to gallop. Pike still won by four yards.

Bob Ferguson, the captain of the Atlantics, was known as "Death to Flying Things." He was also death to eardrums. Ferguson was a forceful man who talked incessantly and was given to rages. Sam Crane, a ballplayer in the nineteenth century and a sportswriter in the twentieth, once wrote of Ferguson, "Turmoil was his middle name, and if he wasn't mixed up prominently in a scrap of some kind nearly every day, he would imagine he had not been of any use to the baseball fraternity and the community in general." Various stories have Ferguson fighting off an angry crowd with a bat and, when he was an umpire, using that same implement to break an impudent player's arm.

-- Daniel Okrent & Steve Wulf

Baseball Anecdotes

4th INNING

The Greatest Triple Play

(1909) The most sensational play ever made? Every fan will give a different answer to this question ... Ed Walsh, the Chicago White Sox pitcher, thinks it was made at Detroit two years ago.

It happened in the game in which Walsh broke the Detroit hoodoo. The Tigers had beaten Walsh every time he faced them. They regarded him as their lawful prey. The game was played in Detroit, and Mullin, who started this season with eleven straight victories for the Tigers, was slated to pitch against Walsh.

Early in the contest George Davis, the veteran shortstop of the Chicago club, secured the only hit made off Mullin and it was enough to win the game. The ball, driven down the first base line into right field, struck a fire hose lying in the grass and bounded into the bleachers for a home run. After that Mullin was invincible.

Toward the end of the game, Detroit opened with the usual rally. Rossman, Detroit's first baseman, leading off in the inning, smashed the ball against the fence for a clean triple. "Dutch" Schaefer drew a base on balls. Schmidt, next at bat, gave the hit-and-run sign and, with both runners in motion, hit a hard bounder down toward third base where Tannehill of Chicago was playing. Tannehill made a perfect scoop and threw the ball to the plate twenty feet ahead of Rossman, who seeing that he was caught, doubled back on the line, hoping to dodge the tag long enough to allow Schaefer to reach third.

Sullivan raced down the line with the ball, driving Rossman before him. Rossman slipped and fell close to third base and just as Sullivan tagged him for the first out, Schaefer slid to third. In the meantime, Schmidt, a slow runner because of an injury to his ankle, had rounded first base and was well on his way to second. Sullivan straightened up and whipped the ball to Rohe who was covering second base and calling for the throw.

As Schmidt slid, Rohe's arm came down with a thump and Schmidt made the second out. The instant Sullivan threw the ball, Schaefer was on his feet and dashing home from third base. The plate had been left unprotected; Sullivan was down near third base. Walsh, the pitcher, yelled for the ball and raced Schaefer to the rubber, closely followed by George Davis. The two runners collided in front of the plate.

Walsh was stunned and Schaefer was thrown ten feet from the plate, alighting on his shoulders. Davis, who arrived about the same time, took the throw and dropped the ball on the struggling Tiger, completing the third out and the most sensational triple play ever made in big leagues.

George Davis, who is a scientist, says that it was not a clean triple, but every man at the ball park went home talking about it in whispers. It is the melodrama of the game which counts in the penciled statement of the autocrat of the box office.

-- Charles E. Van Loan

"Baseball as the Bleachers Like It"

Baseball: A Literary Anthology

5th INNING

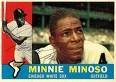

Minnie Minoso: The Negro Leagues

I was born Saturnino Orestes Minoso in 1922 in the small town of Perfico, Matanzaz, Cuba. I had two brothers and two sisters and was raised on a small ranch, where I cut sugarcane. I played baseball at the ranch from the time I was 11 or 12, managing the team and telling the older kids how to play. We would beat the city teams. I was a pitcher, played third, played center. I got the reputation for being the best player. I was "something else." When I first started playing, I had no idea that I'd be able to play anywhere but Cuba. My ambition was just to play professional ball in Cuba. That was every boy's dream on the island. I didn't know anything about the major leagues. My mother never saw me play professional ball because she died in 1941, a year or two before I quit high school and went to Havana. I played semipro ball for two years there, but since I got only pocket money, I worked as a mechanic for a Buick dealer. I'd get $60 a week. Then I played on the Marianao team in the Cuban Winter League. My father saw me play in my prime only in Cuba in winter ball.

I became one of the stars in Cuba and was signed to a contract by the New York Cubans in the Negro National League. So I came to the United States in 1946. I played third base and made the Eastern All-Star team in 1947, when the Cubans won the World Series, and in 1948, my last season in the Negro Leagues. I became one of the stars in Cuba and was signed to a contract by the New York Cubans in the Negro National League. So I came to the United States in 1946. I played third base and made the Eastern All-Star team in 1947, when the Cubans won the World Series, and in 1948, my last season in the Negro Leagues.When Jackie Robinson signed to play in the major leagues, many players in the Negro League thought they had the opportunity also. I wanted to play in the major leagues to prove that I was one of the best ballplayers. I was invited to a tryout with the St. Louis Cardinals, along with a pitcher on the Cubans, Jose Santiago from Puerto Rico. We were so much better than anyone else there. Santiago struck out all 3 batters he faced, and they had to tell me to ease up on my throws because the first baseman wasn't able to handle anything so hard. But the Cardinals didn't really want to look at us. They sent us home. Because of our treatment by the Cardinals we didn't waste our time when another team invited us to a tryout. If they wanted to look at us, they could watch us play in the Negro Leagues.

--Minnie Minoso

We Played the Game

Editor's Note: Minoso played seventeen seasons in The Show, most of them with the Chicago White Sox. He was a seven-time All-Star and three-time Gold Glove (left field). His career numbers: .298, 186, 1023.

6th INNING

Stats: Triple Crown Winners (Pitching)

Top marks in a league for won-lost record, ERA, and strikeouts.

1877 (NL) -- Tommy Bond (BSN) 40-17, 2.11, 170

1884 (NL) -- Charley Radbourne (PRO) 59-12, 1.38, 441

1884 (AA) -- Guy Hecker (LOU) 52-20, 1.80, 385

1888 (NL) -- Tim Keefe (NYG) 35-12, 1.74, 335

1889 (NL) -- John Clarkson (BSN) 49-19, 2.73, 284

1894 (NL) -- Amos Rusie (NYG) 36-13, 2.78, 195

1901 (AL) -- Cy Young (BOS) 33-10, 1.62, 158

1905 (NL) -- Christy Mathewson (NYG) 31-9, 1.28, 208

1905 (AL) -- Rube Waddell (PHA) 27-10, 1.48, 287

1908 (NL) -- Christy Mathewson (NYG) 37-11, 1.43, 259

1913 (AL) -- Walter Johnson (WSA) 36-7, 1.14, 243

1915 (AL) -- Pete Alexander (PHI) 31-10, 1.22, 241

1916 (AL) -- Pete Alexander (PHI) 33-12, 1.55, 167

1918 (NL) -- Hippo Vaughn (CHC) 22-10, 1.74, 148

1918 (AL) -- Walter Johnson (WSA) 23-13, 1.27, 162

1920 (NL) -- Pete Alexander (CHC) 27-14, 1.91, 173

1924 (NL) -- Dazzy Vance (BRO) 28-6, 2.16, 262

1924 (AL) -- Walter Johnson (WSA) 23-7, 2.72, 158

1930 (AL) -- Lefty Grove (PHA) 28-5, 2.54, 209 1930 (AL) -- Lefty Grove (PHA) 28-5, 2.54, 2091931 (AL) -- Lefty Grove (PHA) 31-4, 2.06, 175

1934 (AL) -- Lefty Grove (NYY) 26-5, 2.33, 158

1937 (AL) -- Lefty Grove (NYY) 21-11, 2.33, 194

1939 (NL) -- Bucky Walters (CIN) 27-11, 2.29, 137

1940 (AL) -- Bob Feller (CLE) 27-11, 2.61, 261

1945 (AL) -- Hal Newhouser (DET) 25-9, 1.81, 212

1963 (NL) -- Sandy Koufax (LAD) 25-5, 1.88, 306

1965 (NL) -- Sandy Koufax (LAD) 26-8, 2.04, 382

1966 (NL) -- Sandy Koufax (LAD) 27-9, 1.73, 317

1972 (NL) -- Steve Carlton (PHI) 27-10, 1.97, 310

1985 (NL) -- Dwight Gooden (NYM) 24-4, 1.53, 268

1997 (AL) -- Roger Clemens (TOR) 21-7, 2.05, 292

1998 (AL) -- Roger Clemens (TOR) 20-6, 2.65, 271

1999 (AL) -- Pedro Martinez (BOS) 23-4, 2.07, 313

2002 (NL) -- Randy Johnson (ARI) 24-5, 2.32, 334

BSN: Boston Braves LOU: Louisville Colonels PHA: Philadelphia Athletics PRO: Providence Grays

IMAGE: Lefty Grove

7th INNING

Year in Review: 1903

After a disastrous 1902 season in which it had been outdrawn by the AL by more than a half-million fans, the National League agreed to peace. Ban Johnson rejected the NL's offer to form another 12-team league, and the modern two-major league format was born.

Other points of the new National Agreement included the AL's adoption of the foul-strike rule and the NL's acceptance of an AL franchise in New York. The Agreement also set up a new National Commission consisting of league presidents Harry Pulliam and Johnson, as well as Johnson ally Garry Hermann. This arrangement guaranteed Johnson's paramount influence; he would remain the de facto lord of baseball until the gambling scandals of the late teens brought about the modern sole baseball commissionership.

Johnson gave pitcher/manager Clark Griffith the job of building a successful AL club in New York City. Partially owned by Tammany Hall figure Joseph Gordon, the club was first called the "Highlanders," as a play on the well-known British regument, Gordon's Highlanders, the team's hastily constructed park at 168th and Broadway, the highest point in Manhattan. Later, newspapermen thumbed their noses at a team nickname with British associations and began calling the team the "Yankees."

Both pennant races were laughers. Boston led the American League in runs scored and fewest runs allowed behind slugger Buck Freeman, who hit 13 home runs and drove in 104; fan favorite and runs-scored leader Patsy Dougherty; and pitchers Cy Young (28-9), Long Tom Hughes (20-7), and Bill Dinneen (21-13). They finished 14-1/2 games ahead of a Philadelphia team that featured improved pitching -- thanks to Eddie Plank, Rube Waddell, and rookie Chief Bender -- but an attack weakened by off-years from Harry Davis and Lave Cross. Nap Lajoie's one-man show in Cleveland, including a league-high .344 batting average, could push his team no higher than third place, 15 games out.

Nineteenth century great (and legendary drinker) Ed Delahanty was killed one night in 1903 when he was kicked off a train for disorderly behavior and then pursued it on foot over a bridge above Niagara Falls. He fell in and drowned. Delahanty had a lifetime .346 batting average, behind only Rogers Hornsby among righthanded hitters.

In Honus Wagner's first year as regular shortstop -- he had been playing first, third, short, and the outfield -- Pittsburgh won its third-straight pennant with a 91-49 record. The Flying Dutchman won another batting title at .355, and he and teammates Ginger Beaumont, Fred Clarke, and Tommy Leach monopolized the leader board in most other hitting categories.

Second-place New York had the NL's top pitching staff in Iron Man McGinnity (31-20) and Christy Mathewson (30-13), but John McGraw's club never got close enough to make a race of it. McGinnity lived up to his nickname by totaling 48 starts (fourth-most in modern history), 44 complete games (third-most), and 434 innings (the third-highest total).

-- David Nemec, et al.

The Baseball Chronicle

8th INNING 8th INNINGThe 1903 World Series

Boston Americans (5) v Pittsburgh Pirates (3)

October 1-13

Huntington Avenue Baseball Grounds (Boston), Exposition Park III (Pittsburgh)

Late in the 1903 season, the owners of the two first-place clubs agreed amongst themselves to play a best-of-nine, postseason world championship series. AL Boston came back to win 5-3 after being down 3-1 to the heavily favored Pirates. The star of the series was Pittsburgh's Deacon Phillippe, a great control pitcher who pitched an incredible five complete games, going 3-2 with a 2.86 ERA. The recent war between the leagues and the drama of underdog versus dynasty made the series a big success and led to the formal World Series, which started in 1905 and has continued until today.

Game 1: Pittsburgh 7, Boston 3

Game 2: Boston 9, Pittsburgh 3

Game 3: Pittsburgh 4, Boston 2

Game 4: Pittsburgh 5, Boston 4

Game 5: Boston 11, Pittsburgh 2

Game 6: Boston 6, Pittsburgh 3

Game 7: Boston 7, Pittsburgh 3

Game 8: Boston 3, Pittsburgh 0

BOSTON: Jimmy Collins (3b), Lou Criger (c), Bill Dinneen (p), Patsy Dougherty (p), Duke Farrell (ph), Hobe Ferris (2b), Buck Freeman (of), Tom Hughes (p), Candy LaChance (1b), Jack O'Brien (ph), Freddy Parent (ss), Chick Stahl (of), Cy Young (p). Mgr: Jimmy Collins

PITTSBURGH: Ginger Beaumont (of), Kitty Bransfield (1b), Fred Clarke (of), Brickyard Kennedy (p), Tommy Leach (3b), Sam Leever (p), Ed Phelps (c), Deacon Phillippe (p), Claude Ritchey (2b), Jimmy Sebring (of), Harry Smith (c), Gus Thompson (p), Bucky Veil (p), Honus Wagner (ss). Mgr: Fred Clarke

Bill Dinneen (Boston) started four games, had four complete games, two shutouts, and won three of the four.

9th INNING

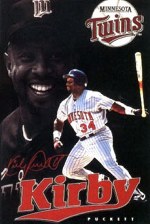

Player Profile: Kirby Puckett

Born: May 14, 1960 (Chicago, IL) Born: May 14, 1960 (Chicago, IL)ML Debut: May 8, 1984

Final Game: September 28, 1995

Bats: Right Throws: Right

5' 8" 210 lb.

Hall of Fame: 2001(Baseball Writers; 423 votes on 515 ballots; 82.14%

His smile brightened up Minneapolis and his blazing bat lit up the American League for 12 enjoyable seasons. Charisma oozed out of Kirby Puckett's Smurfian 5-foot-8 body like water out of a sponge. He brought effervescence, personality and success to a downtrodden Twins franchise while charming his way through a productive career cut short by a serious eye problem in 1996.

It was easy to love the barrel-chested, thick-necked Puckett, who signed autographs with the same enthusiasm that he drove line drives into the gap and chased down fly balls hit into his center field domain. Fans and teammates were swept away by the quick smile; opposing pitchers were swept away by the quick righthanded swing that whipped through the ball from a crouching stance. No area of the ballpark escaped the wicked drives lashed out by one of baseball's classic bad-ball hitters.

Over his 12 big-league seasons, Puckett topped .300 eight times and reached the 200-hit plateau four years in a row. He could finesse you with his deceptive speed or club you with his surprising power. The 1989 A.L. batting champion also was three-time 100-RBI run-producer from his No. 3 spot in the Twins order and the catalyst for Minnesota World Series winners in 1987 and 1991.

Puckett was at his memorable best when scaling the Metrodome's center field fence to rob hitters of home runs, a feat he pulled off with amazing regularity. Twins fans will never forget Game 6 of the 1991 World Series, when Puckett leaped above the fence in the third inning to rob Atlanta's Ron Gant and then hit a game-winning, Series-saving home run in the 11th.

Puckett, at age 35, woke up one morning before the 1996 season with blurred vision in his right eye, a condition later diagnosed as glaucoma. He never played again. The 10-time All Star Game performer finished with a .318 average and 2,304 hits -- and status alongside Harmon Killebrew as the most popular players in Minnesota history.

-- Sporting News

Heroes of the Hall

EXTRA INNINGS

Baseball Dictionary

alley

(1)The portion of the outfield between the center fielder and the left or right fielders; also known as the "power alley" or the "gap". An "alley hitter" is a batter skilled at driving the ball into the alleys. (2) The dirt path between the pitcher's mound and home plate, common in the first half of the 20th century

allow

When a pitcher gives up hits or runs.

All-American Amateur Baseball Association

Organization based in Johnstown, PA that advances, develops and regulates amateur baseball.

All-American Girls Professional League

A league that existed from 1943 to 1954, the brainchild of Chicago Cubs owner Philip Wrigley, and which consisted of as many as fifteen teams playing a hybrid of baseball and softball in such places as Rockford, Ill., Milwaukee, Wis. and Kalamazoo, Mich. The 1992 film A League of Their Own celebrated the league.

All-Star

A player voted by the fans or chosen by the manager to appear in the mid-season All-Star Game. The method of selecting All-Stars have varied over the years. Beginning in 1933 or '34, fans voted for the players using ballots printed in the Chicago Tribune; managers voted in players from 1935 to 1946; fans made the selections from 1947 to 1957; rom 1958 to 1969 players, managers and coaches did the voting; since 1970 the fans do the voting. Critics claim allowing fans to vote turns the process into a popularity contest that sometimes ignores merit. The balloting process is funded by private companies; the Gillette Safety Razor Co. paid for it between 1970 and 1986. In 1987 USA Today began picking up the tab.

All-Star break

A three-day period in mid-July coinciding with the All-Star Game in which no regular season games are played.

All-Star Game

The annual interleague game played in July between players chosen as the best at their position. The players are selected by fan balloting, while pitchers, coaches and substitutes are chosen by selective managers -- who are, these days, the managers of two teams who played in the previous World Series. The first All-Star Game was played July 6, 1933 at Chicago's Comiskey Park, and was the brainchild of Chicago Tribune sports editor Arch Ward. (In that first game, a two-run homer by Babe Ruth gave the AL a 4-2 victory.) Because of the war, an All-Star Game was not played in 1945, and the 1981 contest was postponed to August 9 because of that year's players' strike.

Amateur Softball Association of America

Headquartered in Oklahoma City, OK, the ASA consist of over 100 local associations and more than 260,000 teams involved in slow pitch, fast pitch and modified pitch programs in male, female and coed leagues with players aged 9 to 70. The association was created in 1933 to discuss a set of rules for a game scheduled to be played at Chicago's Century of Progress Exposition.

American Association

(1) This major league existed from 1882 to 1891 as a rival to the National League. It allowed Sunday games and beer sales at ballparks, charging half what the National League charged for admission. Even so, the AA floundered, and four of its teams -- Baltimore, Louisville, St. Louis and Washington were absorbed by the National League.

(2) A primarily Midwestern minor league established in 1903 as Class A through 1907, Class AA through 1945, and then Class AAA from 1946-62 and since 1969.

American Baseball Coaches Association

Organization based in Hinsdale, IL that consists of over 5,000 members and which originated the NCAA World Series.

THIS MATERIAL IS REPRODUCED FOR NON-PROFIT EDUCATIONAL AND SCHOLARLY PURPOSES ONLY, WHICH COMPLIES WITH THE DOCTRINE OF FAIR USE AS EXPRESSED IN THE COPYRIGHT ACT OF 19 OCTOBER 1976, EFFECTIVE 1 JANUARY 1978 (TITLE 17 OF THE UNITED STATES CODE, PUBLIC LAW 94-553, 90 STAT. 2541.)

|