9 Innings 9 InningsA Baseball History Reader

J. Manning, Editor

|

Issue # 2: August 22, 2006

The Effects of Expansion ... "I Beg Your Pardon" ... Polar Baseball ... The Colors of Baseball ... The Amazin' Mets ... Bill Rigney: A Baseball-Crazy Town ... Year in Review: 1901 ... Stats: Managerial Records ... Player Profile: Joe Page ... Baseball Dictionary (aboard - airmail)

|

"Whoever wants to know the heart and mind of America had better learn baseball."

-- Jacques Barzun

1st INNING

The Effects of Expansion

When expansion swelled the American League from eight teams to ten in 1961, and the National League was likewise altered a year later, the major league schedule was revised for the first time since 1904. After playing a 154-game slate for over half a century, both leagues adopted a 162-game season. Under the old schedule, every team played 22 contests against each of the other seven clubs in its loop. With two new franchises added, the number of contests teams played against their rivals was pared to 18. Expansion thereby made for a longer schedule but shorter series. Instead of ... playing four contests each time they met, teams now usually played only three per meeting. One important casualty was the traditional weekend series, which began with a night game on Friday, followed by a Ladies' Day game on Saturday and then a doubleheader on Sunday.

In 1969, a second wave of expansion, which created two new teams in both major leagues, resulted in each circuit splitting into two six-team divisions rather than balloon to an unwieldy 12-team loop. The schedule remained at 162 games, with clubs playing 18 contests against each of their five division rivals and 12 against each of the six clubs in the other division. To determine the pennant winner, it was decided that the two division champions would play a best three-of-five League Championship Series at the conclusion of the regular season. Only the World Series format was left unchanged by schedule-makers in 1969. The restructuring that was done to divide the two leagues into separate divisions resulted in several quixotic geographical arrangements .... Atlanta was placed in the National League West as was Cincinnati, while St. Louis and Chicago got spots in the East. The Chicago American League entry meanwhile was sent to the West Division ....

-- David Nemec & Peter Palmer

1001 Fascinating Baseball Facts

2nd INNING

"I Beg Your Pardon"

My first memory of listening to Herb Score was in my basement. Herb was on the radio telling me about an Indians spring training game from Tucson or Mesa or somewhere. [S]pring training games were tough on Herb. He can -- how can this be said kindly? -- become easily confused. In the spring there are different players going in and out of the game every inning ... but Herb doesn't notice because he likes to sit with his back to the field between innings, working on his tan. But I forgive Herb. He has made a million mistakes, and so have the Indians. The only difference is that Herb is good-natured about it. On the air he sounds like the nicest guy you'd ever want to meet. Then you meet Herb, and guess what? He just may be the nicest guy you've ever met. My first memory of listening to Herb Score was in my basement. Herb was on the radio telling me about an Indians spring training game from Tucson or Mesa or somewhere. [S]pring training games were tough on Herb. He can -- how can this be said kindly? -- become easily confused. In the spring there are different players going in and out of the game every inning ... but Herb doesn't notice because he likes to sit with his back to the field between innings, working on his tan. But I forgive Herb. He has made a million mistakes, and so have the Indians. The only difference is that Herb is good-natured about it. On the air he sounds like the nicest guy you'd ever want to meet. Then you meet Herb, and guess what? He just may be the nicest guy you've ever met.Herb Score has seen more Indians games than anyone, so it's no wonder he has trouble keeping things straight. Herb pitched for the Indians from 1955 to 1959. He returned to the team as a TV broadcaster in 1964, and he moved into the radio booth in 1968. That's five years playing for the Tribe and thirty more as a broadcaster.

"Herb Score has probably watched more bad baseball than anyone in the history of the game," said Joe Tait, one of his partners on radio. Maybe that's why Score's descriptions are like no others. Try some of these:

"There's a two-hopper to Kuiper who fields it on the first bounce."

"Swing and miss, called strike three."

"There's a fly ball deep to right field. Is it fair? Is it foul? It is!"

He called pitcher Efrain Valdez, "Efrem Zimbalist, Jr."

Growing up listening to Herb, then working for him for five years, Nev Chandler is a Herb Score catalog.

"One game we were playing Boston at the Stadium, and the Tribe was losing 7-4 in the bottom of the eighth," said Chandler. "The Indians had the bases loaded, two outs. Andre Thornton hit a fly ball down the left field line. It appeared to have the distance for a homer. The only question was whether it would stay in fair territory. But Boston's Jim Rice went deep into the corner, timed his leap perfectly -- I saw him catch the ball and bring it back into the park. Suddenly Herb yelled, 'And that ball is gone. A grand slam home run for Andre Thornton. That is Thornton's twenty-second home run of the year and the Indians lead, 8-7.'

"As Herb was saying this, he wasn't looking at the field. He was marking his scorebook. I saw Rice running in with the baseball. Herb was still talking about the home run. I snapped my fingers, and Herb looked up to see the Red Sox leaving the field.

"Herb said, 'I beg your pardon. Nev, what happened? Did Rice catch the ball?'

"Trying to bail Herb out, I said, 'Rice made a spectacular catch. He went up and over the wall and took the home run away. It was highway robbery.'

"Herb said, 'I thought the ball had disappeared into the seats. Well, I beg your pardon. The Indians do not take the lead. After eight innings, it is Boston 7, Cleveland 4.'

"Then we went to commercial, and Herb acted as if nothing had happened. I would have been completely flustered. But Herb just corrects himself and keeps going."

That is why Indians fans love Herb Score. He is unpretentious, making his way through games as best he can. He's just Herb being Herb, and being Herb Score sometimes means taking strange verbal sidetrips. When Albert Belle hit a home run into the upper deck in left field that supposedly went 430 feet, Score asked, "How do they know it went 430 feet? Do they measure where the ball landed? Or do they estimate where the ball would have landed if the upper deck hadn't been there? And if there had been no upper deck, then how do they know how far the ball would have gone?"

Score answered none of those age-old questions of the baseball universe. He was just wondering about it one moment, and then it was forgotten by him the next.

But not by Indians fans. One of their favorite pastimes is to tell one another what Herb said the night before. One of my favorites:

CHANDLER: "That base hit makes Cecil Cooper 19-for-42 against the Tribe this year."

SCORE: "I'm not good at math, but even I know that is over .500."

Well, it's not quite. But I'll give Herb the benefit of the doubt.

-- Terry Pluto

The Curse of Rocky Colavito

3rd INNING

Polar Baseball

On August 1, 1960, the American nuclear-powered submarine Seadragon left Portsmouth, New Hampshire, to chart a new Northwest Passage across the top of the world to the Pacific.

In the course of the historic journey, the Seadragon would become the first submarine to dive under icebergs. At one juncture, while negotiating a ticklish 850-mile passage through the Canadian archipelago, Comdr. George P. Steele consulted a 140-year-old explorer's journal. Shortly before the boat reached the North Pole, the navy briefly lost radio contact with her. On the night of August 25, 1960, the Seadragon broke through the ice at the pole and reported all was well. The crew was fine, if in need of some exercise. Skies were clear, with temperatures in the high twenties. Baseball weather. In the course of the historic journey, the Seadragon would become the first submarine to dive under icebergs. At one juncture, while negotiating a ticklish 850-mile passage through the Canadian archipelago, Comdr. George P. Steele consulted a 140-year-old explorer's journal. Shortly before the boat reached the North Pole, the navy briefly lost radio contact with her. On the night of August 25, 1960, the Seadragon broke through the ice at the pole and reported all was well. The crew was fine, if in need of some exercise. Skies were clear, with temperatures in the high twenties. Baseball weather."We have maneuvered the ship through light ice to where we can put a life raft over ... to ferry over a party to play baseball," Commander Steele radioed. "The men are wearing the warmest clothes they can get."

The 360 degrees of longitude and the International Dateline converge at the Pole. Thus the polar baseball diamond was arranged so a home run would travel "from today into tomorrow and from one side of the world to the other." A runner leaving home plate also reached first base twelve hours later. Nobody hit one into next week.

Even at the North Pole, the pastime proved to be a great equalizer: the enlisted men beat the officers, 13-10.

-- David Cataneo

Baseball Legends and Lore

4th INNING

The Colors of Baseball

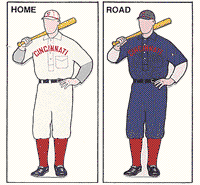

For many years baseball teams wore flannel uniforms with conservative markings -- white at home and gray on the road. But new materials and styles of the '60s -- especially public acceptance of men wearing bright colors -- returned the baseball uniform to the rainbow days of the 19th century. For many years baseball teams wore flannel uniforms with conservative markings -- white at home and gray on the road. But new materials and styles of the '60s -- especially public acceptance of men wearing bright colors -- returned the baseball uniform to the rainbow days of the 19th century.The first uniformed team, the New York Knickerbockers of 1849, wore long cricket-style pants, but the first professional team, the Cincinnati Red Stockings of 20 years later, began the tradition of wearing shorter pants and long colored stockings.

In the National League's first year, the Chicago White Stockings had a different colored hat for each player, including a red, white, and blue topping for pitcher/manager Al Spalding.

At its winter meeting of 1881, the league voted to have its clubs wear stockings of different colors: Cleveland dark blue, Providence light blue, Worcester brown, Buffalo gray, Troy green, Boston red, and Detroit yellow. Position players had to wear shirts, belts, and caps as follows: catchers scarlet, pitchers light blue, first basemen scarlet and white, second basemen orange and blue, third basemen blue and white, shortstops maroon, left fielders white, center fielders red and black, right fielders gray, and substitutes green and brown. Pants and ties were universally white and shoes were made of leather.

The plan caused too much confusion and was quickly dropped, but color remained part of the game. The Chicago White Stockings wore black uniforms and white neckties under Cap Anson in 1888 and had daily laundry service. The weekly Sporting Life complained that the pants were so tight they were "positively indecent."

In 1889 Pittsburgh wore new road uniforms consisting of black pants and shirt with an orange lace cord, an orange belt, and orange-and-black striped stockings.

The St. Louis Browns, whose nickname changed to the Cardinals when their uniforms took on more red, wore shirts with vertical stripes of brown and white, complete with matching caps.

Pre-1900 styles dictated lace shirts with collars and ties, open breast pockets, and occasionally red bandana handkerchiefs as good-luck tokens. John McGraw, manager of the Giants, was the first baseball official to order uniform shirts without collars, and he also discarded the breast pockets, which sometimes served as a resting place for a batted ball.

The Giants and Phillies started the trend of wearing white at home and dark, solid colors on the road and, in 1911, the concept of whites and grays became mandatory -- partly because it was sometimes hard to tell the home club from the visitors.

In an effort to lure fans to the ballpark, Charles Finley outfitted his Kansas City Athletics in green, gold, and white suits in the '60s and invited the scorn of the baseball world. Some of his own players expressed embarrassment at playing in "softball unforms." Others likened the suits to pajamas.

But the Finley concept of color -- which included mix-and-match combinations of caps, shirts, and pants -- caught on quickly. In 1971 the Pittsburgh Pirates introduced form-fitting double knits, complete with pullover tops, and six years later designed three sets of uniforms -- gold, black and striped -- that could be worn in nine different combinations.

-- Don Schlossberg

The Baseball Almanac

[IMAGE: Cincinnati Reds, 1902]

5th INNING

The Amazin' Mets

"I don't know what's going on," Richie Ashburn said, "but I know I've never seen it before." "It" was the expansion Mets of 1962, who managed to lose 120 games under the bemused leadership of an aged Casey Stengel. Ashburn, as it happened, hit .306 that year, but no other regular topped .275. The team's best pitcher, Roger Craig, lost 24 games. The only category in which any Met led the league was errors. The Mets gave up a staggering 948 runs, some 322 more than the Pirates, who finished fourth. The team ERA was 5.04. And they concluded the season 60-1/2 games out of first place -- that is, two months out of first. "I don't know what's going on," Richie Ashburn said, "but I know I've never seen it before." "It" was the expansion Mets of 1962, who managed to lose 120 games under the bemused leadership of an aged Casey Stengel. Ashburn, as it happened, hit .306 that year, but no other regular topped .275. The team's best pitcher, Roger Craig, lost 24 games. The only category in which any Met led the league was errors. The Mets gave up a staggering 948 runs, some 322 more than the Pirates, who finished fourth. The team ERA was 5.04. And they concluded the season 60-1/2 games out of first place -- that is, two months out of first.The paradigm of those Mets was Marvin Eugene Throneberry -- appropriately, his initials spelled "MET."

On June 17, 1962, Throneberry had his most memorable day in baseball. In the bottom half of the first inning in a game against the Cubs, he charged into third base with a triple, only to be called out on an appeal by the Cubs' Ernie Banks for not having touched first. That was when Casey Stengel, steaming out of the dugout to protest, was told by first-base coach Cookie Lavagetto that Throneberry had missed second, too.

It was in the top of the inning, though, that Marvelous Marv had established his pattern for the day. The Cubs' Don Landrum had led off the game with a walk, and then Al Jackson picked him off first. Landrum was caught in the ensuing rundown, but the call was negated when Throneberry was called for obstruction.

Finally, in the bottom of the ninth, with the Mets down 8-7, two men on and two men out. Throneberry came to the plate with the opportunity to redeem himself. Needless to say, he struck out.

At season's end, the Mets were 40-120. They had had losing streaks of 9, 11, 13, and 17 games. As he prepared to depart for his off-season recuperation, Throneberry asked, "You think the fish will come out of the water to boo me this winter?"

Leonard Shecter reported this exchange between Throneberry and Johnny Murphy, the old Yankee pitcher who negotiated salaries for the early Mets:

Throneberry: "People came to the park to holler at me, just like Mantle and Maris. I drew people to games."

Murphy: "You drove some away, too."

T: "I took a lot of abuse."

M: "You brought most of it on yourself."

T: "I played in the most games of my career, 116."

M: "But you didn't play well in any of them."

In a game against the Giants during the '62 Mets' 17-game losing streak. Roger Craig threw perilously close to Orlando Cepeda, and shortstop Elio Chacon took umbrage at a Willie Mays baserunning move. In short order, Mays took care of the tiny Chacon, and the 210-pound Cepeda disposed of Craig. The next morning, Newsday's coverage of the game began, "The Mets can't fight, either."

....After that first horrible season, the Mets announced they were calling up their three best minor league pitchers: Larry Bearnarth, who'd been 2-13 at Syracuse; Tom Belcher, 1-12 at Syracuse; and Grover Powell, 4-12 at Auburn and Syracuse.

Still the spring of 1963 dawned hopeful for the Mets, who were confident they were an improved team. Then the Cardinals beat them 8-0 an opening day at the Polo Grounds. Said Stengel, "We're still a fraud."

-- Daniel Okrent & Steve Wulf

Baseball Anecdotes

6th INNING

Bill Rigney: A Baseball-Crazy Town

[1947] I fell in love with New York. There [were] ... all the great restaurants and supper clubs, there were stores and Automats, there was music and movies and shows, there were subways and els and double-decker buses, there were newstands everywhere you looked, and Central Park was a beautiful playground .... I guess I started to feel a bit like a celebrity because I'd be walking down Broadway at night and Giants fans would call to me. The New York fans knew who you were and who they were. They were proud of their teams. That made a huge impression on a young player like me. Until I came to New York, I didn't realize fans could care so much whether a team won or lost. New York was a baseball-crazy town. There were all those newspapers and great sportswriters: Jimmy Cannon of the Post, Arthur Daley of the Times, Red Smith of the Herald Tribune, Dick Young of the Daily News. And we had the best broadcasters: The Giants' Russ Hodges, the Dodgers' Red Barber, and the Yankees' Mel Allen. [1947] I fell in love with New York. There [were] ... all the great restaurants and supper clubs, there were stores and Automats, there was music and movies and shows, there were subways and els and double-decker buses, there were newstands everywhere you looked, and Central Park was a beautiful playground .... I guess I started to feel a bit like a celebrity because I'd be walking down Broadway at night and Giants fans would call to me. The New York fans knew who you were and who they were. They were proud of their teams. That made a huge impression on a young player like me. Until I came to New York, I didn't realize fans could care so much whether a team won or lost. New York was a baseball-crazy town. There were all those newspapers and great sportswriters: Jimmy Cannon of the Post, Arthur Daley of the Times, Red Smith of the Herald Tribune, Dick Young of the Daily News. And we had the best broadcasters: The Giants' Russ Hodges, the Dodgers' Red Barber, and the Yankees' Mel Allen.[Giants owner Horace] Stoneham built a team around the home run rather than pitching and defense. He liked to watch guys who could hit the long ball. He got my roomie, first baseman Johnny Mize, and catcher Walker Cooper from the Cardinals. Cooper hit 6 homers in 3 games at one point. Outfielders Bobby Thomson, who had come up briefly in 1946, Willard Marshall, and Sid Gordon were all pull hitters with power. In 1947 we set a major league record with 221 home runs. Mize tied Pittsburgh's Ralph Kiner for the homer title with 51, Marshall was third with 36, Cooper was fourth with 35, and Thomson was fifth with 29 ... We were the only National League team with more than one player with 100 RBIs, and we had three, with Mize, Cooper, and Marshall. We'd win 10-9, not 1-0 ....

With Stoneham's emphasis on hitting, our pitching was weak .... Mel Ott would have been a better manager if he'd had better pitchers. Another problem is that he hired his friends as his coaches. Ott was a great guy and everyone loved him and wanted to play well for him. Dodgers manager Leo Durocher was talking about Otty when he said, "Nice guys finish last."

Even in my first exhibition game against the Dodgers I could tell there was a strong, strong rivalry between the Dodgers and the Giants. I could taste it, smell it. There was never a rivalry to match it. On the field, the two teams detested each other. As the Giants got better, beginning in 1947, the rivalry became even more intense. There were now three good teams in New York. The rivalry wasn't based on jealousy. It was competitive, it was fun. Much had to do with our being in the same area. There was no such thing as a fan of two teams. You liked the Giants, the Dodgers, or Yankees, and hated the other two teams. That the fans cared so much about their favorite teams fed the rivalries ....

When Jackie Robinson joined the Dodgers in 1947, there was no better player in the league. He was the toughest out and there would be no better competitor during my entire career. He was carrying the cross for the black man and was he ever the right man to do that. He had a lot of talent and a strong personality ....

There were a lot of people who didn't like baseball being integrated. Prejudice was prevalent, without a doubt ... Of course, Jackie's great ability and desire to win had to be admired ... We all kept an eye on him, watching his progress. It didn't matter if we rooted for him to make it, which many of us did, because he was going to make it in spite of everything. He was that dedicated. He was also mature, not a brash young man. People forget that he wasn't young but almost 30.

-- Bill Rigney

We Played the Game

NOTE: Read Bill Rigney: The Rookie in Issue # 1.

7th INNING

Year in Review: 1901

Seeking his third consecutive pennant with Brooklyn in 1901, manager Ned Hanlon instead was overwhelmed by a Pittsburgh team that had not been similarly decimated by AL raiders. Hanlon, before 1901, suffered the defection of Fielder Jones, Lave Cross and Joe McGinnity. Unable to replace the three stars, Brooklyn sank to third place while the Phillies advanced a notch to the second spot. Neither club, though, could pose much of a challenge to the Pirates, who would soon emerge as the first dynasty of the new century.

In 1901, Pittsburgh lost only one player of consequence to the upstart AL -- third baseman Jimmy Williams -- and pilot Fred Clarke more than replaced him with Tommy Leach. Rookie Kitty Bransfield seized the first base job, and another newcomer, Lefty Davis, took over in right field alongside Ginger Beaumont in center and Clarke in left. This combination proved lethal, giving the Pirates an outfield with a combined average above .300. Honus Wagner, meanwhile, found a new niche at shortstop after incumbent Bones Ely was permitted to take his .208 batting average to the AL. With Deacon Phillippe winning 22 games, Jack Chesbro 21, and Jesse Tannehill chipping in with 18 victories and a league-leading 2.18 ERA, the Pirates hardly missed fractious Rube Waddell, the 1900 ERA champion, who was sold to the Chicago Cubs in May. Attaining first place on June 16, Pittsburgh remained there the rest of the way but had to subdue a late threat from Philadelphia before claiming the first NL pennant in the city's history.

The AL, in its fledgling season as a major league, also had a tight race into September. Led by 33-game winner Cy Young, slugging first sacker Buck Freeman, and third baseman-manager Jimmy Collins, its three prize thefts from the NL, Boston had the inside track on the first AL major-league pennant. But a late slump by pitchers Ted Lewis and George Winter opened the door for the Chicago White Sox to cop the honor under Clark Griffith, who had been swiped prior to the season from the crosstown Cubs by Sox owner Charlie Comiskey. Comiskey had also managed the Sox to the AL flag in 1900 when the loop was still a minor league. He later opted to give up the reins to focus on the front office because he believed the dual role would be too burdensome with the AL now endeavoring to achieve major-league status. The AL, in its fledgling season as a major league, also had a tight race into September. Led by 33-game winner Cy Young, slugging first sacker Buck Freeman, and third baseman-manager Jimmy Collins, its three prize thefts from the NL, Boston had the inside track on the first AL major-league pennant. But a late slump by pitchers Ted Lewis and George Winter opened the door for the Chicago White Sox to cop the honor under Clark Griffith, who had been swiped prior to the season from the crosstown Cubs by Sox owner Charlie Comiskey. Comiskey had also managed the Sox to the AL flag in 1900 when the loop was still a minor league. He later opted to give up the reins to focus on the front office because he believed the dual role would be too burdensome with the AL now endeavoring to achieve major-league status.With the two leagues at loggerheads, a postseason clash to settle bragging rights for the 1901 season was still a pipe dream.

-- David Nemec & Saul Wisnia

Baseball: More Than 150 Years

IMAGE: Chicago White Stockings logo, 1901

8th INNING

Managerial Records

Most Years as a Manager

AL: 50, Connie Mack, Philadelphia, 1901-1950

NL: 32, John McGraw, Baltimore, 1899, New York (Giants), 1902-1932

Most Games Won as Manager

AL: 3582, Connie Mack, Philadelphia

NL: 2690, John McGraw, Baltimore and New York

Most Pennants Won as Manager

AL: 10, Casey Stengel, New York (Yankees)

NL: 10, John McGraw, New York (Giants)

Most World Series Won as Manager

AL: 7, Joe McCarthy, New York & Casey Stengel, New York

NL: 4, Walter Alston, Brooklyn/Los Angeles

Most Consecutive Pennants Won as Manager

AL: 5, Casey Stengel, New York, 1949-53

NL: 4, John McGraw, New York, 1921-24

Most Clubs Managed to Pennants

3, Bill McKechnie, Pittsburgh, St. Louis, Cincinnati

3, Dick Williams, Boston, Oakland, San Diego

First Manager to Pilot Pennant Winners in Two Leagues since 1901

Joe McCarthy, Chicago (NL), 1929, New York (AL), 1932

Only Man to Win a Pennant in His Lone Season as a Manager

George Wright, Providence (NL), 1879

Highest Career Winning Percentage as Manager

.615, Joe McCarthy, 24 seasons, 2125 wins and 1333 losses

-- David Nemec

Great Baseball Feats, Facts & Firsts

9th INNING

Player Profile: Joe Page Player Profile: Joe PageNickname: "Fireman"

Born: October 28, 1917 (Cherry Valley, PA)

ML Debut: April 19, 1944

Final Game: May 25, 1954

6'2" 205

Bats: Left Throws: Left

Joseph Francis Page, a powerful left-handed hurler out of the coal-mining region of Pennsylvania, made his Yankee debut on April 19, 1944. That season he posted a 5-1 record and secured a place on the All-Star team. Then a shoulder injury lessened his effectiveness and he drifted back and forth in mediocrity from starter to reliever. However, Bucky Harris saved Page's career in 1947 by putting him in the bullpen. A 14-8 record with seventeen saves and a 2.15 ERA in relief that season got Page a lot of attention. Those fourteen relief wins lasted as the AL record until Luis Arroyo snapped it in 1961.

Page followed up his regular-season heroics with outstanding hurling in the 1947 World Series, getting the save in game one and winning the clincher, holding the Dodgers to one hit in five scoreless innings. He was the first World Series Most Valuable Player. In 1948, Page led the league with fifty-five appearances and became an All-Star for the third time....

Under Casey [Stengel], Page saved twenty-seven games and posted a 13-8 record. He closed out the Red Sox in the next-to-last game of the season, enabling the Yankees to win the pennant. In the World Series, Page won game three and held the Dodgers scoreless in game five from the seventh inning on.

Joe Page's final Yankee season was 1950. Perhaps it was the heavy workload through the years, perhaps it was just time. But after only seven seasons as a Yankee, he was done. Joe Page still ranks in seventh place in franchise history with seventy-six saves.

-- Harvey Frommer

A Yankee Century

In mid-August [1949] Boston began a late surge that seriously threatened the Yankees' hold on first place, but because of [Casey] Stengel's uncanny foresight and his players' excellent execution, the team was somehow hanging onto the lead despite widespread injuries to key players. The pitching staff was holding up satisfactorily, and Joe Page, the controversial relief pitcher, was at the top of his form, sneering at the hitters, and throwing bullets at them ....

Joe Page was Henry Fielding's Tom Jones in a baseball uniform, a tall, handsome celebrity with jet-black hair and a toothpaste smile, a rounder who enjoyed being noticed in public, a night owl who greeted the rosy-fingered sunrise through bloodshot eyes after a lusty night's play.

For two years of his checkered career Joe Page was the most valuable pitcher in the American League, a left-handed relief specialist who would insolently saunter to the mound from the right-field bullpen, his jacket saucily slung over his shoulder partially covering the number 11 on the back of his pinstripe uniform. When he got there he took the ball from the manager and nonchalantly fired a half-dozen warm-up pitches of medium velocity. Then after the batter stepped in, Page would survey the runners dancing off the bases, sneer defiantly at the batter, and then streak exploding, rising fastballs past the usually overmatched batsman.

....Page came from the coal country of the Allegheny valley where human life was cheap. During the depths of the Depression the life of a miner wasn't worth much more than the cost of a good headstone .... In mining society the threat of death was really the way of life, something which had to be stoically accepted because its likelihood was so immediate. Few miners put money in the bank for a rainy day. Instead they took that money and lived life day by day. This was Joe Page's milieu, a lifestyle most of his teammates could never understand. They thought him to be irresponsible, out for himself, and an attention-seeker who loved public adulation whereas they wanted to be left alone .... Page's reaction to this rejection was a veneer of indifference, as he traveled his side of the tracks while they traveled theirs.

It was this veneer that also drove his managers into fits of rage when they would chastise him, only to see him shrug his shoulders. Few could understand how a man could be so excellent one year and so mediocre the next, yet seem so indifferent to his change of fortune.

Page reached the Yankees in 1944 ... [and] started the season winning five of his six starts and was named to the 1944 All-Star team by manager [Joe] McCarthy. There was a tremendous amount of pride in his local community when he was named to play in the game, being held in Pittsburgh that year. But on the day that was to be his triumphant homecoming, his father suffered a stroke, and Page, instead of playing, sped to the local hospital where his father died before he could see his son pitch in the majors ....

In 1946 McCarthy's frustrations with managing the losing wartime Yankee teams and with fighting a seemingly losing battle to reform Page finally surfaced on a plane trip from Cleveland to Detroit in May .... McCarthy slipped into the aisle seat next to Page and propped up his right leg... to lock Page in. He tapped Page firmly on the arm to get his attention. "You're going to sit and listen to what I have to say," McCarthy said.

"Sure," said Page breezily.

"What the devil's the matter with you?" McCarthy asked.

"Nothing," Page said.

"When are you gonna settle down and start pitching? How long do you think you can get away with this?" McCarthy's voice level was beginning to rise.

"Get away with what?" Page asked annoyedly. "I'm not trying to get away with anything. I'm doing the best I can. What do you want outta me?"

McCarthy began shouting, so that he was audible throughout the entire plane. The other players and the press, embarrassed, tried to act like they weren't listening and like nothing unusual was happening. "Who the hell do you think you're kidding?" McCarthy shouted, his Irish temper at the boiling point. "I'll tell you what I'm going to do. I'm going to send you back to Newark, and you can make your four hundred dollars a month for all I care."

Page, unruffled, shrugged his shoulders. "That's okay with me," he said. "You wanna send me to Newark, send me to Newark. Maybe I'll be happier there."

....But that afternoon when the plane landed in Detroit, McCarthy did not go to the ball park. He was too hypertense to manage. After a rest in his hotel room, he flew directly home to his Tonawanda, New York, farm. The next day he telephoned in his resignation as Yankee manager, a job he had held since 1931.

....Page didn't become a big winner until 1947 under the much more live-and-let-live Bucky Harris, who switched him to the bullpen. In '47 Page appeared in fifty-six games, winning fourteen and saving twenty others. He was fourth in the voting for Most Valuable Player. In the world series he saved the first and third games. In the seventh and deciding game Page entered in the top of the fourth inning, and over the final five innings he blew his fast ball past the Dodgers, allowing one hit and no runs. After the final game, the entire team toasted Joe Page and his live fast ball, including owner Larry MacPhail who earlier in the year had dispatched a female private detective to follow Page around. Columnist Ed Sullivan wrote about Page and the female detective, and before long there were stories that she had fallen in love with Page and was sending MacPhail the most glowing reports.

After Page's 1947 triumphs, he spent the entire winter celebrating, and the following year he arrived in camp thirty pounds overweight, and after crash-dieting to lose the weight, he was weak all season. He also suffered from a tired arm after Harris used him with mixed success in fifty-five games ....

When Stengel became manager in '49, Page, rested and fit, regained his 1947 form and pitched in a record sixty games, winning thirteen, saving twenty, and holding the opposition in fourteen other games without getting credited in the records. It was another incredible, magical year -- the last such season he would ever have.

In 1950 he again suffered a tired arm, pitching with mixed success, and then in 1951, in spring training, Page was on the mound when his right leg, the striding leg, slipped after his windup, and, releasing the ball off-balance, he tore the bursar muscle in his pitching arm. His career was over ....

-- Peter Golenbock

Dynasty: The New York Yankees, 1949-1964

EXTRA INNINGS

Baseball Dictionary

aboard

On base. First used: McClure's Magazine, Apr. 1907.

ace

(1) In the early days of baseball, the term used for a score, as called for in the 1845 rules of the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club. First used: 1845, New York Morning News, Oct. 21. (2) A team's best pitcher. First used: 1902, The Sporting News, Nov. 15.

Baseball lore and tradition have always laid the origin of this term to one man. In 1869, pitcher Asa Brainard won 56 out of 57 games played by the Cincinnati Red Stockings, baseball's first professional team. From then on, according to lore, any pitcher with a dazzling string of wins was called an "Asa," which later became "ace." -- Dickson Baseball Dictionary.

across the letters

A pitch passing the batter chest high.

activate

Returning a player to a team's active roster following injury or suspension.

activity

There is "activity in the bullpen" when one or more of a team's relief pitchers are warming up.

advance

What a batter does when he moves a baserunner one or more bases with a hit, ground out, fly out or sacrifice; what a baserunner does when he moves from one base to the next.

advance scout

A scout who studies the strengths and weaknesses of a team that his team will play next.

"The term was first used by Casey Stengel, according to Tony Kubek (in George F. Will's Men at Work, 1990). The practice dates to the early 1950s when the Brooklyn Dodgers began sending an advance man to the Polo Grounds or to Philadelphia to scout the teams on their way to Ebbets Field." -- Dickson Baseball Dictionary.

aggressive hitter

A batter who swings at pitches out of the strike zone.

ahead in the count

When a pitcher has more strikes than balls in the count. Can also be applied to a batter who has a count containing more balls than strikes.

airmail

To throw the ball over another player's head.

THIS MATERIAL IS REPRODUCED FOR NON-PROFIT EDUCATIONAL AND SCHOLARLY PURPOSES ONLY, WHICH COMPLIES WITH THE DOCTRINE OF FAIR USE AS EXPRESSED IN THE COPYRIGHT ACT OF 19 OCTOBER 1976, EFFECTIVE 1 JANUARY 1978 (TITLE 17 OF THE UNITED STATES CODE, PUBLIC LAW 94-553, 90 STAT. 2541.)

|