9 Innings 9 InningsA Baseball History Reader

J. Manning, Editor

|

Issue # 19: February 1, 2008

Tinkers to Evers to Chance ... The Typology of Japanese Ballplayers ... Married to Mickey Mantle ... Destination: Louisville Slugger Museum ... Pee Wee Reese: The Kid from Kentucky ... Stats: Batting Average (Career) ...Year in Review: 1918 ... The 1918 World Series ... Player Profile: Johnny Mize ... They Played the Game: Bert Blyleven, Tom Brown, Bob Hazle, Cal Hubbard, Bert Shepard

|

"I don't want to play golf. When I hit a ball, I want someone else to go chase it."

-- Rogers Hornsby

1st INNING

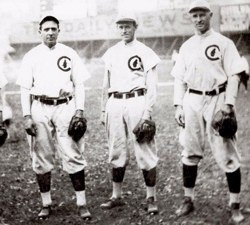

Tinker to Evers to Chance

[A] couple of things about the "poem," published in the New York Evening Mail on July 10, 1910. First of all the title is not "Tinker to Evers to Chance." Here's the verse as it originally appeared, along with its original title: [A] couple of things about the "poem," published in the New York Evening Mail on July 10, 1910. First of all the title is not "Tinker to Evers to Chance." Here's the verse as it originally appeared, along with its original title:Baseball's Sad Lexicon

These are the saddest of possible words,

"Tinker-to-Evers-to Chance."

Trio of Bear Cubs fleeter than birds,

Tinker to Evers to Chance.

Ruthlessly pricking our gonfalon bubble,

Making a Giant hit into a double,

Words that are weighty with nothing but Trouble.

"Tinker-to-Evers-to-Chance."

--Franklin P. Adams.

For Frank Adams it was a "sad lexicon" because he was a fan of the New York Giants. In fact, Adams wrote the verse because he was in such a hurry to get to the ballpark. As he later remembered, "I wrote the poem because I wanted to get to the game, and the foreman of the composing room ... said I needed eight lines to fill."

What exactly is a "gonfalon"? According to my dictionary, it's "a banner suspended from a crosspiece," so apparently Adams was saying that Tinker and pals were hurting the Giants' pennant chances with their double-play antics.

It's been fashionable in recent years to question the double-play skills of Tinker and Evers ... To be sure, it's quite possible, perhaps even likely, [Tinker and Evers] (and Chance, too) might not be in the Hall of Fame if not for the poem. Their career stats simply are not typical of Hall of Fame players, even middle infielders. It's also true ... that from 1906 through 1911 the Cubs never led the National League in double plays. Individually, Evers never led N.L. second basemen in double plays, and Tinker topped N.L. shortstops in double plays only once .... Writing negatively of their Hall of Fame qualifications in 1999, USA Today's Tom Weir noted, "Despite the poetry, the three ranked as the National League's best double-play combo only once."

Well, there's more to playing the infield than raw numbers of double plays. The Cubs featured an outstanding pitching staff ... that permitted relatively few baserunners. In turn, that limited the number of double-play opportunities available to the Cub infielders.

So is there an easy way to evaluate the Cubs' double-play abilities given the statistics at our disposal? Yes, there is. Bill James has come up with a system to measure what he calls expected double plays for a team, based on (essentially) the number of runners the opposition has on first base and the estimated number of ground balls hit by the opposition....

.... Yes, the Cubs only tied for third in total double plays [from 1906 to 1910], which is nothing special in an eight-team league. But ... [they] turned 50 more double plays than expected, easily the most in the National League. So while Tinker and Evers never really dominated the National League in a single season, nobody could match their consistency .... [I]t also seems safe to say that they were probably the best of their era and an important factor in the Cubs' amazing run.

It's too bad that they couldn't have enjoyed each other a little more. It seems that Joe Tinker and Johnny Evers, paragons of keystone teamwork, once went upwards of two years without speaking to each other. In 1936, New York World-Telegram columnist Joe Williams got to talking with Evers about the old-time Cubs, and Williams asked if all the stories about the feud were true.

"That's right," admitted Mr. Evers. "We didn't even say hello for at least two years. We went through two World Series without a single word. And I'll tell you why .... [O]ne day -- it was early in 1907 -- he threw me a hardball. It wasn't any further than from here to there .... It was a real hardball. Like a catcher throwing to second. And the ball broke my finger .... I yelled at him, 'You so and so!' He laughed. That's the last word we had for -- well, I just don't know how long."

Other sources have reported that the feud actually began in 1905, when there was a mix-up over a cab the two were supposed to share. By all accounts, though, Evers was an incredibly high-strung fellow.

.... Frank Chance got so sick of listening to his irascible second baseman that he considered shifting Evers to the outfield. These days, I suppose you'd call Evers an extreme type-A personality, and he didn't really get along with anybody, which is probably why everyone called him "The Crab." Evers missed most of the 1911 season after suffering a nervous breakdown. Nevertheless, he succeeded Chance as player-manager in 1913, leading a disgusted Tinker to demand a trade. After the season, Evers himself was traded to the Boston Braves, for whom he played a major role in their miraculous, World Series-winning 1914 campaign ....

As for Frank Adams, he reportedly thought his famous lines "weren't much good."

-- Rob Neyer & Eddie Epstein

Baseball Dynasties

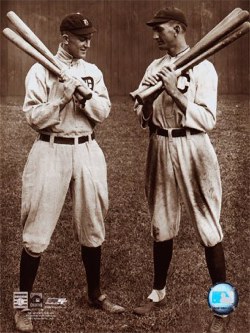

IMAGE: (L-R) Joe Tinker, Johnny Evers and Frank Chance

2nd INNING

The Typology of Japanese Ballplayers

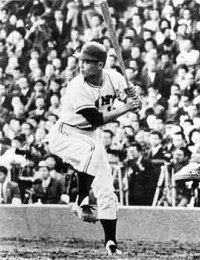

In the end, the Red Sox apparently decided to spend more than $100 million to get the Japanese pitcher Daisuke Matsuzaka in a Boston uniform for the next six seasons, a daring financial outlay for an athlete who has never thrown a pitch in the major leagues or sampled the mildly insane rivalry between the Red Sox and Yankees.

For intrigued baseball fans in the United States, Matsuzaka's relevant statistics are no-brainers: 26 years old, 6 feet, 187 pounds and a 108-60 record with a 2.95 earned run average in eight seasons with the Seibu Lions.

But what many fans, the Red Sox front office and even Matsuzaka's determined agent, Scott Boras, may not realize is that in the eyes of the Japanese, Matsuzaka's most revealing statistic might be his blood type, which is Type O. By Japanese standards, that makes Matsuzaka a warrior and thus someone quite capable of striking out Alex Rodriguez, or perhaps Derek Jeter, with the bases loaded next summer.

In Japan, using blood type to predict a person's character ... is akin to the equally unscientific use of astrological signs by Americans to predict behavior, only more popular ....

Japanese popular culture has been saturated by blood typology for decades. Dating services use it to make matches. Employers use it to evaluate job applicants. Blood-type products -- everything from soft drinks to chewing gum to condoms -- have been found all over Japan.

....A person can have one of four blood types, A, B, AB or O, and while the most common blood type in Japan is Type A, many of the more prominent Japanese players are like Matsuzaka, Type O. That group includes Hideki Matsui of the Yankees, Kazuo Matsui of the Colorado Rockies ... and Tadahito Iguchi of the Chicago White Sox.

Sadaharu Oh, the great Japanese home run hitter? He is type O, too, as is Kei Igawa, the 27-year-old Hanshin Tiger left-hander who has until Dec. 28 to sign with the Yankees. Sadaharu Oh, the great Japanese home run hitter? He is type O, too, as is Kei Igawa, the 27-year-old Hanshin Tiger left-hander who has until Dec. 28 to sign with the Yankees.In Japan, people with Type O are commonly referred to as warriors because they are said to be self-confident, outgoing, goal-oriented and passionate. According to Masahiko Nomi, a Japanese journalist who helped popularize blood typology with a best-selling book in 1971, people with Type O make the best bankers, politicians and -- if you are not yet convinced -- professional baseball players.

But there are exceptions to any categorization, and in this instance one of them would appear to be Ichiro Suzuki of the Mariners, who has become one of the great hitters in major league baseball since joining ... Seattle in 2001. Suzuki is Type B.

"That makes sense in a way," said Jennifer Robertson, a professor of anthropology at the University of Michigan who specializes in Japanese culture and history. Robertson added that people with Type B, known as hunters, are said to be highly independent and creative.

And creative would be a good adjective to describe Suzuki at the plate, where he sprays the ball to all fields and sometimes seems to hit the ball to an exact spot. Suzuki set the major league record for hits in a season with 262 in 2004.

....In a sense, all this will play out when Matsuzaka faces Hideki Matsui for the first time next season. In Boston and New York, it will be Red Sox pitcher versus Yankee hitter, right-hander versus left-hander, high-priced Japanese athlete versus high-priced Japanese athlete. In Japan, it will be all that and more. May the best Type O prevail.

-- David Picker

December 14, 2006

New York Times

IMAGE: Sadaharu Oh, Japan's home run king

3rd INNING

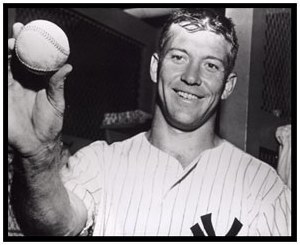

Married to Mickey Mantle

I met Mickey Mantle for the first time after a high school football game in Commerce, Oklahoma, in 1949. He didn't say a word. I guess that's why I remembered him afterwards. I thought it was so odd.

Right then (in my mind, anyway), I was more a celebrity than he was, for I was drum majorette of the Picher High School band and a soloist at the First Baptist Church of Picher, and I'd sung at nearby army camps. Mickey had been graduated from Commerce High School that spring and was working as an electrician in the local lead and zinc mines, where his father was a ground boss.

I had never heard of Mickey, although Picher is only three miles from Commerce, and he had been playing baseball around those parts since he was five years old, from peewee leagues to pro ball. He'd even been signed by the New York Yankees at the time of his graduation. But I, like most of the other folks then in Ohlahoma, was strictly a football fan. I knew so little about baseball that, on one of our early dates, I asked Mickey how many time-outs they could have during an inning....

It was hard for me to understand, when we first started going together, why he said so firmly that we couldn't get married until he had made good with the Yankees. But all his life ... my husband has been trained for just one thing -- to play baseball. I'll never forget last year, when he got home on Christmas Eve from ther tour he had made with Bob Hope of army camps in Alaska. He saw all the presents I had put out for the children and said: "I can't remember ever having any toys but baseballs and bats."

Both Mickey's dad and his grandfather were crazy about baseball and I guess they decided when Mickey was born that he was going to be a major leaguer .... They taught Mickey to be a switch hitter, his grandpa throwing to him right-handed, and his dad left-handed. When he was just a little fellow, they would have him out in the back yard afternoons taking batting practice until it got dark. Of course, this is largely why he is where he is today, and Mickey is fully aware of the debt he owes them both. Grandpa died in 1935; I never knew him. But I got to know his dad during Mickey's first year with the Yankees.

I had just graduated from high school and was working in the bank at Picher during the summer .... Then Mickey got into a slump. The Yankees sent him back to Kansas City, which just about broke his heart. Mickey admitted he even cried when he heard the news. Kansas City was about 150 miles from Commerce, but Dad and Mother Mantle drove over there often to see Mickey play and keep up his morale. They sometimes took me along, too.

When Mickey made good in Kansas City and the Yankees recalled him, Dad Mantle was even more thrilled than Mickey. He got a group together to go to see Mickey play in the World Series in New York .... But in the second game, Mickey, who was playing right field, tripped on one of the drains in the outfield and tore all the ligaments in his right knee. They had to carry him off the field on a stretcher. I can imagine how Dad Mantle must have felt. He hurried to the clubhouse and went down to Lenox Hill Hospital with Mickey. But as Dad Mantle tried to help Mickey out of the cab, poor Dad collapsed .... The doctors at Lenox Hill ... found out he was in the last stages of cancer, and told Mickey his father couldn't live more than six months.... When Mickey made good in Kansas City and the Yankees recalled him, Dad Mantle was even more thrilled than Mickey. He got a group together to go to see Mickey play in the World Series in New York .... But in the second game, Mickey, who was playing right field, tripped on one of the drains in the outfield and tore all the ligaments in his right knee. They had to carry him off the field on a stretcher. I can imagine how Dad Mantle must have felt. He hurried to the clubhouse and went down to Lenox Hill Hospital with Mickey. But as Dad Mantle tried to help Mickey out of the cab, poor Dad collapsed .... The doctors at Lenox Hill ... found out he was in the last stages of cancer, and told Mickey his father couldn't live more than six months....Dad Mantle came home shortly after the Series was over, but Mickey had to stay in the hospital about a month. When he got home, he asked me to marry him as soon as possible .... Mickey was under tremendous pressure. He wanted to make good both for himself and for his dad. He also had financial reasons. He had been voted a full share of the World Series money and had used it to pay the mortgage on the family house. But he was now the sole support of two families and he was aware of his responsibilities. Dad Mantle died in May. There was a night game with the Indians and Mickey played because he knew his father would have wanted it. Then he went home to the funeral.

....Mickey and I were very young that first year, very inexperienced, and both of us were spoiled. I was lonesome and homesick .... I also had my first experience with baseball fans. Mickey used to come home from the park followed by a string of boys and girls. Sometimes their kidding wasn't so good-natured, especially if he'd had a bad day. If he didn't stop to sign autographs, they threw ink at him. Several good shirts and jackets were ruined, and we couldn't afford that. His Fan Club, girls around 14 years old, used to settle for hanging around me if they couldn't find Mickey. When I did my daily marketing, I was followed down the street and into the stores by a group of little girls wearing jackets with "Mickey Mantle" on their backs.

....So far as I'm concerned, I would settle for Mickey's quitting when he finishes ten years of baseball in the majors, which will be after the 1960 season. But if Mickey's legs hold out, I don't think he will stop that soon. There is nothing else he was ever trained for, and nothing he loves to do as much.

--Merlyn Mantle (as told to Christy Munro)

"The Mickey Mantle I Know" (1957)

The Best of Baseball Digest

4th INNING

Destinations: Louisville Slugger Museum

The 120-foot bat that stands at the front of the museum suggests something special. And few visitors are disappointed. The legacy of Hillerich & Bradsby dates back to 1884, when the company started making Louisville Slugger bats in its family woodworking shop. The legend goes like this: The owner's son, Bud Hillerich, attended a local baseball game and, noticing that local star Pete Browning was in a hitting slump, brought him to the shop to have a new bat made. With his new weapon, Browning clubbed three hits the next day, and soon word spread of the effective new bat manufactured by Hillerich & Bradsby. Today, visitors to the factory and museum in downtown Louisville watch bats being made and experience a baseball history museum that is rivaled only by Cooperstown. Everyone, from Honus Wagner and Ty Cobb to Babe Ruth, have sworn by the famous bats made from Pennsylvania white ash. The 120-foot bat that stands at the front of the museum suggests something special. And few visitors are disappointed. The legacy of Hillerich & Bradsby dates back to 1884, when the company started making Louisville Slugger bats in its family woodworking shop. The legend goes like this: The owner's son, Bud Hillerich, attended a local baseball game and, noticing that local star Pete Browning was in a hitting slump, brought him to the shop to have a new bat made. With his new weapon, Browning clubbed three hits the next day, and soon word spread of the effective new bat manufactured by Hillerich & Bradsby. Today, visitors to the factory and museum in downtown Louisville watch bats being made and experience a baseball history museum that is rivaled only by Cooperstown. Everyone, from Honus Wagner and Ty Cobb to Babe Ruth, have sworn by the famous bats made from Pennsylvania white ash.The Hillerich name is still prominent in the business; the Bradsbys have been gone since the late 1930s. The company has always been located in Louisville, except for a few years when it moved across the Ohio River to Indiana. The company produces 2,000 wooden bats per workday, using high-speed lathes. Some go to young players, but 60-70 percent of all major league players have contracts with Hillerich & Bradsby. The bats crafted for professionals match precise computer specifications for each player. The company also makes golf clubs, hockey sticks and aluminum bats at other facilities, but wooden baseball bats are made exclusively at the Louisville plant.

Tours end at the gift shop, appropriately named "A League of Your Own." Every person who takes a tour also receives a miniature Louisville Slugger as a souvenir. The Louisville Slugger Museum, which entertains 300,000 visitors a year, is open Monday through Saturday.

Location: 800 West Main Street, Louisville, KY

-- Chris Epting

Roadside Baseball

5th INNING

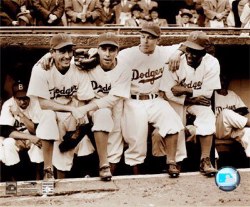

Pee Wee Reese: The Kid from Kentucky

I was born on a farm between two small towns called Bradingberg and Ekron, about fifty miles from Louisville .... But I loved off the farm at age seven. It was 1925, and at the time farming was difficult. We grew tobacco, some corn, just something to survive on. We were very poor, five children, trying to make a living on not too good of a farm.

When we moved to Louisville, my dad did odd jobs .... Course, my dad had no education. Of the children, I was the only one graduated from high school. There was not a lot of education in my family. It was the early '30s, the Depression years .... We all worked. I worked selling box lunches, and I delivered papers .... When I got out of high school in 1936, jobs were tough to get, and I worked in a furniture company and Mengel Box Company, making twenty-five cents an hour, and you worked ten hours a day, which added up to $2.50. And then I went to work for the telephone company, and I got a big raise to $18 a week. I was an apprentice cable splicer.

When I finally decided to go and play ball in 1938, the man who got me the job at the telephone company said to me, "Pee Wee, I think you're making a big mistake by quitting your job and going away to play baseball" ....

I had only played five games my senior year in high school. I was not large enough. Hell, when I graduated, I was about five foot four and weighed 120 pounds. I played ball for my church team, the New Covenant Presbyterian Church, and we won the city championship in 1937, and we won a trip to the 1937 World Series. A man by the name of Captain Neal, who was the general manager of the Louisville Colonels, which was a Double-A ball team, evidently noticed me, and he asked me if I wanted to play professional ball.

And I was fortunate it wasn't a good club. It was independently owned, so consequently we didn't have too many good players, so I got to stay with the team and play. So sometimes it helps to be in the right place at the right time.

I played for this 1938 club, and the next year the team was purchased by Donie Bush and Frank McKinney, and we had a working agreement with the Boston Red Sox. In '39 they brought up players from the Red Sox, so we ended up that year with a pretty good ballclub. In fact, we ended up winning the Little World Series.

And at this point I thought I was going directly to the Red Sox. No question. Bobby Doerr, the Red Sox second baseman, told me he was looking forward to it. Joe Cronin was the manager and the shortstop and getting older, and Bobby figured I would be there.

Supposedly Bush and McKinney bought the Colonels just so they could acquire my contract .... But evidently Mr. Cronin thought he could play a few more years, and he talked them out of buying me, and Bush and McKinney sold me to the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1939 for $75,000.

I was very disappointed. It was July, and I was going to the all-star game in Kansas City, the American Association all-stars against the Kansas City Royals, who were leading the league at that point, and I was on the train, and one of the Louisville writers told me that I had been sold to Brooklyn ....

I didn't go with the Dodgers until spring training of 1940. We were training in Clearwater, and I weighed all of 155 pounds soaking wet. Looking like I was sixteen, I guess. When I got there, I didn't know any of the fellas on the team, and I was scared to death. But within a few days, Dolph Camilli, Harry Lavagetto, and Pete Coscarart, which was the whole infield, made me feel at home. Wherever they went, they took me with them. Why did they do it? Beats the hell out of me. I was just a scared kid from Kentucky, and these guys had been up in the majors for a while .... I didn't go with the Dodgers until spring training of 1940. We were training in Clearwater, and I weighed all of 155 pounds soaking wet. Looking like I was sixteen, I guess. When I got there, I didn't know any of the fellas on the team, and I was scared to death. But within a few days, Dolph Camilli, Harry Lavagetto, and Pete Coscarart, which was the whole infield, made me feel at home. Wherever they went, they took me with them. Why did they do it? Beats the hell out of me. I was just a scared kid from Kentucky, and these guys had been up in the majors for a while ....When I got there, Leo [Durocher] at this time was thirty-five or so, and he was managing, and he probably wanted someone to take his place. But I got hit in the head by Jake Mooty of the Cubs, and I was in the hospital for eighteen days .... And then after I came back, in August I slid into second base and broke a bone in my ankle, so I was out for the rest of the year. So I only played eighty-four games my first year.

When I opened the 1941 season with a brace on my ankle, it got me to wondering, because it was a tough year. We won the pennant, and I guess I contributed something, but I didn't have too good a year. I was having problems at bat and in the field, and it got to where I didn't feel too easy in the games. But naturally, I would never ask out of the lineup, though Lee MacPhail was pressuring Leo to take me out, and he did for one game. But Leo hadn't played in a while, and it was tough on him. Leo had a little trouble with a fly ball, going back over his head, and he decided he better put me back in the lineup.

-- Peter Golenbock

Bums: An Oral History of the Brooklyn Dodgers

IMAGE: (L-R), Spider Jorgenson, Pee Wee Reese, Ed Stankey, Jackie Robinson

6th INNING

Stats: Batting Average (Career)

1. Ty Cobb .366 ... 2. Rogers Hornsby .358 ... 3. Joe Jackson .356 ... 4. Ed Delahanty .346 ... 5. Tris Speaker .345 ... 6. Ted Williams .344 ... 7. Billy Hamilton .344 ... 8. Dan Brouthers .342 ... 9. Babe Ruth .342 ... 10. Harry Heilmann .342 ... 11. Pete Browning .341 ... 12. Willie Keeler .341 ... 13. Bill Terry .341 ... 14. George Sisler .340 ... 15. Lou Gehrig .340 ... 16. Jesse Burkett .338 ... 17. Nap Lajoie .338 ... 18. Tony Gwynn .337 ... 19. Riggs Stephenson .336 ... 20. Al Simmons .334 ... 21. John McGraw .334 ... 22. Paul Waner .333 ... 23. Eddie Collins .333 ... 24. Wade Boggs .333 ... 25. Mike Donlin .333 ... 26. Stan Musial .331 ... 27. Sam Thompson .331 ... 28. Heinie Manush .330 ... 29. Cap Anson .329 ... 30. Rod Carew .328 ... 31. Honus Wagner .327 ... 32. Tip O'Neill .326 ... 33. Bob Fothergill .325 ... 34. Jimmie Foxx .325 ... 35. Earle Combs .325 ... 36. Joe DiMaggio .325 ... 37. Babe Herman .324 ... 38. Hugh Duffy .325 ... 39. Joe Medwick .324 ... 40. Edd Roush .323 ... 41. Sam Rice .322 ... 42. Ross Youngs .322 ... 43. Kiki Cuyler .321 ... 44. Charlie Gehringer .320 ... 45. Chuck Klein .320 ... 46. Pie Traynor .320 ... 47. Mickey Cochrane .320 ... 48. Ken Williams .319 ... 49. Kirby Puckett .318 ... 50. Earl Averill .318 ... 51. Arky Vaughan .318 1. Ty Cobb .366 ... 2. Rogers Hornsby .358 ... 3. Joe Jackson .356 ... 4. Ed Delahanty .346 ... 5. Tris Speaker .345 ... 6. Ted Williams .344 ... 7. Billy Hamilton .344 ... 8. Dan Brouthers .342 ... 9. Babe Ruth .342 ... 10. Harry Heilmann .342 ... 11. Pete Browning .341 ... 12. Willie Keeler .341 ... 13. Bill Terry .341 ... 14. George Sisler .340 ... 15. Lou Gehrig .340 ... 16. Jesse Burkett .338 ... 17. Nap Lajoie .338 ... 18. Tony Gwynn .337 ... 19. Riggs Stephenson .336 ... 20. Al Simmons .334 ... 21. John McGraw .334 ... 22. Paul Waner .333 ... 23. Eddie Collins .333 ... 24. Wade Boggs .333 ... 25. Mike Donlin .333 ... 26. Stan Musial .331 ... 27. Sam Thompson .331 ... 28. Heinie Manush .330 ... 29. Cap Anson .329 ... 30. Rod Carew .328 ... 31. Honus Wagner .327 ... 32. Tip O'Neill .326 ... 33. Bob Fothergill .325 ... 34. Jimmie Foxx .325 ... 35. Earle Combs .325 ... 36. Joe DiMaggio .325 ... 37. Babe Herman .324 ... 38. Hugh Duffy .325 ... 39. Joe Medwick .324 ... 40. Edd Roush .323 ... 41. Sam Rice .322 ... 42. Ross Youngs .322 ... 43. Kiki Cuyler .321 ... 44. Charlie Gehringer .320 ... 45. Chuck Klein .320 ... 46. Pie Traynor .320 ... 47. Mickey Cochrane .320 ... 48. Ken Williams .319 ... 49. Kirby Puckett .318 ... 50. Earl Averill .318 ... 51. Arky Vaughan .318IMAGE: Ty Cobb and Joe Jackson

7th INNING

Year in Review: 1918

[With the United States at war and baseball deemed a nonessential occupation, the government gave baseball players until September 1 to enlist, get a war-related job, or be reclassified with a lower draft number. The cutoff date was extended to September 15 for the two teams headed for the World Series -- ed.]

The aborted 1918 season had no orderly ending, and the Cubs and Red Sox wound up in a tarnished World Series.

NL---Since the Cubs had been pulling away from the Giants since June and were 10-1/2 games ahead when play ended after Labor Day, there was nothing tarnished about their fifth pennant in 13 years. They had bought [Pete] Alexander from the Phillies, but he was drafted three games into the season. [Hippo] Vaughn, Claude Hendrix, and Lefty Tyler ... were their top pitchers, [Fred] Merkle their first baseman, Fred Mitchell their manager ....

Cincinnati was third, lots of hitting, no pitching, and [Hal] Chase acting up again. [Christy] Mathewson couldn't stand him, since by now his betting, fixing, and corrupting others was so blatant. On August 9, with the hearty approval of his players, Mathewson suspended Chase. Before the month was out, Matty was in the army, where he would be seriously wounded (by gas) in France later in the year ....

AL---The Red Sox were in first place by 2-1/2 games over Cleveland and four over Washington when play stopped, but since they'd been leading from April on, their pennant was legitimate enough. The new owner, Frazee, had made Jack Barry playing-manager in 1917, but Barry was in the army so Ed Barrow managed. Barrow had a rich baseball background and had been president of the International League during the Federal League War, essentially a front-office man with little field experience but astute judgment. He didn't see why [Babe] Ruth couldn't play the outfield on days he didn't pitch, so the Babe's pitching record was only 13-7 (with a 2.22 ERA), but 59 games in the outfield and 13 at first base provided him with 317 times at bat, plus 57 walks. He hit .300, with 26 doubles, 11 triples, and 11 homers. That tied him for the home-run lead with Tilly Walker, now in Philadelphia, who had almost 100 more at bats. Meanwhile, [Carl] Mays was 21-13, a suddenly effective Sam Jones 16-5, and Joe Bush, bought from the A's, 15-15. The Red Sox had no pitching problems.

The Yankees, in their first year under [Miller] Huggins, came in a respectable fourth. The White Sox, with half their team in war work or service, fell to sixth. [George] Sisler, with fifth-place St. Louis, hit .341, second only to Cobb's .382, but led the league with 45 stolen bases (to Cobb's 34) ....

....The curtailed schedule, unplanned, meant that, among other things, players would lose four to six weeks of expected pay, or nearly 20 percent of a year's total. In addition, they learned that, without their having been consulted or informed, the World Series prize-money formula had been changed, so that teams finishing second, third, and fourth could get some prize money, too. Furthermore, anticipating less interest, the owners decided to charge regular ticket prices instead of the customary higher ones, lowering the player pool total (60 percent of the receipts of the first four games), and the players had already pledged 10 percent of their share to the Red Cross. The Commission estimated that the winner-loser shares would be $2,000 and $1,400. The three preceding years they had averaged $3,800 and $2,600.

Leonard Koppett

Koppett's Concise History of Major League Baseball

NL: Chicago, 84-45 ... New York, 71-53 ... Cincinnati, 68-60 ... Pittsburgh, 65-60 ... Brooklyn, 57-69 ... Philadelphia, 55-68 ... Boston, 53-71 ... St. Louis, 51-78

AL: Boston, 75-51 ... Cleveland, 73-54 ... Washington, 72-56 ... New York, 60-63 ... St. Louis, 58-64 ... Chicago, 57-67 ... Detroit, 55-71 ... Philadelphia, 52-76

8th INNING

The 1918 World Series

Boston Red Sox (4) v Chicago Cubs (2)

September 5-11

Comiskey Park (Chicago), Fenway Park (Boston)

Game 1: Boston 1, Chicago 0

Game 2: Chicago 3, Boston 1

Game 3: Boston 2, Chicago 1

Game 4: Boston 3, Chicago 2

Game 5: Chicago 3, Boston 0

Game 6: Boston 2, Chicago 1

BOSTON: Sam Agnew (c), Joe Bush (p), Jean Dubuc (ph), Harry Hooper (of), Sam Jones (p), Carl Mays (p), Stuffy McInnis (1b), Hack Miller (ph), Babe Ruth (p, of), Wally Schang (of), Everett Scott (ss), Dave Shean (2b), Amos Strunk (of), Fred Thomas (3b), George Whiteman (of). Mgr: Ed Barrow

CHICAGO: Turner Barber (ph), Charlie Deal (3b), Phil Douglas (p), Max Flack (of), Claude Hendrix (p), Charlie Hollocher (ss), Bill Killefer (c), Les Mann (of), Bill McCabe (ph), Fred Merkle (1b), Bob O'Farrell (c), Dode Paskert (of), Charlie Pick (2b), Lefty Tyler (p), Hippo Vaughn (p), Chuck Wortman (2b), Rollie Zeider (3b). Mgr: Fred Mitchell

Red Faber and Hippo Vaughn both tied Christy Mathewson's 1911 World Series record of 27.0 innings pitched. Lefty Tyler set a World Series record by issuing eleven walks -- a record tied by Lefty Gomez in 1936 and Allie Reynolds in 1951.

[T]he players began the Series in Chicago, September 5. Ruth faced Vaughn. The Red Sox scored in the fourth ... and that was enough. Ruth won 1-0. Then Bush faced Tyler. The Cubs had a three-run second, with Tyler delivering a two-run single, and Tyler won 3-1. Then Boston won 2-1, with Mays and Vaughn (on one day's rest) allowing seven hits each.

The attendance, at low prices, had been 19,000, 20,000, and 27,000. The Commission announced that the player shares would be cut to $1,200 and $800. On the train back to Boston, the players got together and formed a four-man committee to talk to the Commission. They met the morning of the fourth game, September 9. The players said either postpone the plan for sharing with other first-division teams until after the wart, or give us the originally promised shares .... The Commission pleaded poverty ... and claimed that only the leagues themselves could change rules. Interpreting that as stalling, the players decided to play no more games.

At game time, there were 22,000 people in Fenway Park but no players on the field. American League president Ban Johnson, apparently drunk, appealed to them. With Johnson clearly in no condition to talk seriously, the players decided to go ahead, for the sake of the public and their own feeling for the game, exacting only a promise of no retribution for the brief but undeniable strike action.

Starting an hour late (which mattered, since there were no lights), Ruth faced Tyler. In the fourth, Ruth knocked in two runs with a triple. In the eighth, his scoreless streak ended at 29 innings plus .... But Boston made it 3-2 in its half. In the ninth, Ruth needed Bush's help to nail it down.

Chicago won the next day 3-0, on Vaughn's five-hitter against Jones. The sixth game followed the same pattern: a three-hitter by Mays, beating Tyler 2-1 on two unearned runs.

The Red Sox had been in five World Series -- 1903, 1912, 1915, 1916, 1918 -- and had won them all ....

(Leonard Koppett, Koppett's Concise History of Major League Baseball)

9th INNING

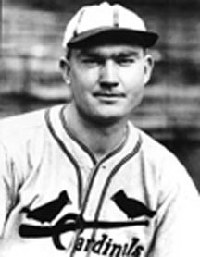

Player Profile: Johnny Mize Player Profile: Johnny MizeFull name: John Robert Mize

Nickname: The Big Cat

Born: January 7, 1913 (Demorest, GA.)

ML Debut: April 16, 1936

Final Game: September 26, 1953

Bats: Left Throws: Right

6' 2" 215

Hall of Fame: 1981 (Veterans Committee)

During Johnny Mize's eleven-season career with the St. Louis Cardinals and the New York Giants, he was THE slugger in the National League, leading in home runs in 1939, '40, '47, and '48, and in RBIs in 1940, '42, and '47. In 1939 he hit 28 home runs to win the home-run title, and in 1940 Mize set a Cardinal team record for home runs with 43. That year Mize might have had a chance to break Babe Ruth's season record of 60 home runs, but a temporary wire mesh fence was erected above the low right-field wall, and many of the 31 doubles and 13 triples he hit banged off the screen instead of going into the stands for home runs. In 1942 his 137 RBIs led the league, and after he spent three years in the Navy, he hit 51 home runs for the Giants in 1947, becoming only the second left-handed batter in baseball history to hit more than 50 home runs in a season. That year his 138 runs batted in also led the league. He hit 40 home runs to lead the league in 1948, and his 125 RBIs made it the eighth season that he batted in over 100 runs.

Mize was 36 years old when the Yankees bought him from the Giants toward the end of the 1949 season. Mize played first base for manager Stengel and during his five-year Yankee stay, he became Stengel's number one pinch hitter, leading the league in pinch hits in 1951, '52, and '53.

When Mize finally retired at the end of the '53 season, he had hit more home runs than any other active player. His 359 career home runs placed him sixth on the all-time home-run list behind an exclusive group of Hall-of-Famers: Babe Ruth (714), Jimmy Fox (534), Mel Ott (511), Lou Gehrig (493), and Joe DiMaggio, two ahead at 361. Behind Mize were two more Hall-of-Famers, Ted Williams, at 337 the only active player close to him, and Hank Greenberg (331).

He was 40 years old when he retired, a member of the exclusive 2000-hit club, and one of three men in the history of the game to have hit a home run in each of the American League and National League parks in which he played....

The Yankees were fortunate to acquire Mize in August of '49. He had led the National League in homers for the past two years and had been named to the All-Star team in '49, but the Giants had hired a new manager, Leo Durocher, in mid-'48, and Durocher preferred players with speed and finesse who could steal bases and hit-and-run, and he began to bench some of the older, less mobile veterans including Mize. In midsummer of 1949 the Yankees were playing the Giants in the annual Major's Trophy game for charity, and Stengel, knowing that Mize was not playing regularly, approached him before the game. "How you doing?" Stengel asked the big first-baseman. "I'm not playing much," Mize responded. "Over here you'd be playing," Stengel said. Stengel then urged George Weiss to acquire him. Mize had a .324 lifetime batting average, he had been a league All-Star for nine years, and he would be a perfect batsman to challenge Yankee Stadium's short right-field porch. For the Yankees there were also disturbing rumors that the Red Sox were trying to get him.

....When Mize came to the Yankees, he and Stengel got along famously. For many years Mize had been a one-man destruction gang against Stengel's Dodger and Brave teams, and Casey highly respected Mize's knowledge of the mechanics of hitting. When he wasn't starting, Mize would sit on the bench next to Stengel and act as the unofficial batting coach, making suggestions and annoying some players who didn't particularly desire his criticism ....

--Peter Golenbock

Dynasty: The New York Yankees, 1949-1964

"Mize's nickname was the 'Big Cat,' but he couldn't move at all around first base. However, he could hit. He had a great eye and a beautiful compact swing. He hit .337 in 1946, but injuries kept his homer total down to 22. Then in 1947 he hit those 51 homers and led the league with 137 runs and 138 RBIs. What a year! He was a cigar smoker. The first thing he'd do every morning on the road was light a cigar .... He'd get up and walk to the window and lift the shade and look out and find a flag. He'd figure out from the direction that flag was blowing the direction of the wind at the ballpark. If the wind would be blowing out, Mize would lie back in bed and puff that cigar and say, 'Roomie, I'm going to hit one or two today.' And he would."

-- Bill Rigney

We Played the Game

"Another thing Stengel ... liked to do was acquire a veteran to help down the stretch. In 1949 we purchased Johnny Mize, the former home run champion with the Cardinals and Giants. He had a bunch of key hits for us in September. He did so well that the Yankees would make it a practice to pick up veterans for stretch drives in future years."

-- Billy Johnson

We Played the Game

Your arm is gone, your legs likewise

But not your eyes,, Mize, not your eyes

--Dan Parker, New York Daily Mirror (1950)

EXTRA INNINGS

They Played the Game

Bert Blyleven

(1970-90, 1992)

Pitcher who at the age of 30 had started season openers for four major league clubs. Blyleven was the opening-day starter for the Texas Rangers in 1977, for the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1979 and 1980 and, five days past his 30th birthday, for the Cleveland Indians in 1981. [In 1986 Blyleven set a major league record by allowing 50 home runs. The following year he served up 46 -- ed.]

BORN: April 6, 1951 (Zeist, Holland) 287-250, 3.31

All-Star 1973, 1985

Tom Brown

(1963)

The only man to play major league baseball and also appear in football's Super Bowl. Brown, from the University of Maryland, was a first baseman-outfielder who played in 61 games for Washington in 1963 and batted .147 with one home run. He then played with Green Bay of the National Football League from 1964 through 1968, starting at safety for the Packers in Super Bowls I and II, and finished his NFL career with the Washington Redskins in 1969.

BORN: December 12, 1940 (Laureldale, PA) .147, 1, 4

Bob Hazle

(1955, 1957-58)

Called up from Class AAA Wichita (where he was batting only .279), Hazle earned the nickname "Hurricane" by hitting .403 in 41 games for Milwaukee in 1957 and helping the Braves to the National League pennant. The outfielder's only other big-league experience consisted of six games in 1955 and 63 games in 1958.

BORN: December 9, 1930 (Laurens, SC) .310, 9, 37

Cal Hubbard

The only man inducted into both the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, NY, and the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton, Ohio. Hubbard was a standout lineman for nine seasons (1927-33, 1935-36) in the National Football League, an American League umpire for 16 years (1936-51) and then a supervisor of umpires.

BORN: October 31, 1900 (Keytesville, MO)

Bert Shepard

(1945)

Pitcher whose big-league career consisted of one appearance -- and that came after amputation of his right leg below the knee (as a result of injuries suffered when his plane was shot down during World War II). Pitching on an artificial leg against the Boston Red Sox in the second game of an August 4, 1945 doubleheader at Washington's Griffith Stadium, Shepard worked 5-1/3 innings of relief for the Senators and allowed only three hits and one run. He walked one batter and struck out two as the Red Sox prevailed, 15-4.

BORN: June 28, 1920 (Dana, IN)

-- The Sporting News

Baseball: A Doubleheader Collection of Facts, Feats & Firsts

THIS MATERIAL IS REPRODUCED FOR NON-PROFIT EDUCATIONAL AND SCHOLARLY PURPOSES ONLY, WHICH COMPLIES WITH THE DOCTRINE OF FAIR USE AS EXPRESSED IN THE COPYRIGHT ACT OF 19 OCTOBER 1976, EFFECTIVE 1 JANUARY 1978 (TITLE 17 OF THE UNITED STATES CODE, PUBLIC LAW 94-553, 90 STAT. 2541.)

|