9 Innings 9 InningsA Baseball History Reader

J. Manning, Editor

|

Issue # 17: December 5, 2006

The Mets in the Sixties ... The Baseball Hotel ... A Baseball Game in 1901 ... Minor League Stars ... Vic Power: From Puerto Rico to Yankee Stadium (Part 2) ... Stats: Games ... Year in Review: 1916 ... The 1916 World Series ... Player Profile: Casey Stengel ... They Played the Game

|

"I never feel more at home than at a ballgame."

-- Robert Frost

1st INNING

The Mets in the Sixties

[T]he Mets were created as a compromise solution to the Continental League's threatened incursion into the majors.... The franchise's first moves included adopting the blue (Dodgers) and orange (Giants) colors of its local predecessors .... [P]rincipal owner Joan Payson and club chairman M. Donald Grant [chose] ... George Weiss, the 66-year-old architect of the great Yankee teams of the late 1940s and 1950s, who had been forced into retirement in the Bronx [for general manager].... [T]he Mets were created as a compromise solution to the Continental League's threatened incursion into the majors.... The franchise's first moves included adopting the blue (Dodgers) and orange (Giants) colors of its local predecessors .... [P]rincipal owner Joan Payson and club chairman M. Donald Grant [chose] ... George Weiss, the 66-year-old architect of the great Yankee teams of the late 1940s and 1950s, who had been forced into retirement in the Bronx [for general manager]....Stengel, who had also been forcibly retired by the Yankees, signed on with the team as manager, but that turned out to be only one of his roles. Confronted with expansion players who were to constitute one of the worst teams in baseball history, Stengel...worked the press and television (and, through them, the fans) tirelessly to represent his charges as New York's biggest entertainment attraction. From February to October for almost four years, hardly a day went by without the sports pages reporting some bizarre (or bizarrely stated) observation from the Old Professor on the sorry state of his team. The public relations performance worked to endear the incompetent Mets to many of the same fans who, only a few years before, would have sulked if their Dodgers or Giants had failed to win the pennant....

Going for familiar names in the expansion draft and subsequent trades, the Mets filled their roster with aged stars like Gil Hodges, Richie Ashburn, Gus Bell, and Gene Woodling. Also found appealing were players with an Ebbets Field pedigree -- Hodges, Charlie Neal, Don Zimmer, Roger Craig, and Clem Labine. What it all added up to was a record-shattering [1962] season of 40 wins and 120 losses that included nine straight losses to open the season, an 11-game losing streak between August 9 and August 21, and a 17-game losing skein between May 21 and June 6....

Despite the concentration of ex-Dodgers like Hodges and declining stars like Ashburn, the New Breed ended up devoting most of its attention to other players -- perceived as more appropriate symbols for the various flaws in the human condition the Mets brought to mind. Among them were Rod Kanehl, who could play all the infield and outfield positions, but none of them well; Choo Choo Coleman, a catcher whose main skill was chasing down passed balls; Elio Chacon, a shortstop whose lack of English extended to "I've got it" and led him into almost daily collisions with oncharging outfielders; and Al Jackson, a pitcher of genuine talent who ... in the words of Stengel, had to be relieved on occasion before 'he committed suicide on the mound.' Most of all there was Marv Throneberry, a first baseman whose feats of missing popups, ground balls, and bases became the most enduring emblem of the early Mets.

The groaning laughter from the grandstands and the media failed to impress Weiss, accustomed to collecting pennants and World Series trophies from his days with the Yankees. Already irritated [that] the team had to play its first two years in the deteriorating cavern that was the Polo Grounds, he imported and exported dozens of players in the vain attempt to match the play of at least fellow-expansion Houston .... A dour man, Weiss was also slow to realize the promotional value of the sheets and placards carried to the Polo Grounds by fans bent on proclaiming their sentiments about the team; only after his confiscation policy was blasted in the press did he rescind the order and give impetus to the banners that were the become a cardinal feature of the ballpark.

In their first four seasons the Mets never lost fewer than 109 games and never ended a season closer to first place than 40 games. The "instant recognition" philosophy of players continued with the purchase of all-but-done stars like Duke Snider, Yogi Berra, and Warren Spahn. Another 1963 import was Jimmy Piersall, the Fear Strikes Out center fielder who marked his 100th home run by trotting around the bases backward and who was then quickly traded because, according to Stengel, there wasn't room for two clowns on the team. For those seeking signs of an eventual improvement in the play of the club, the main source of hope was second baseman Ron Hunt and first baseman Ed Kranepool. Hunt, whose specialty was getting hit by pitched balls, finished second only to Pete Rose in the voting for the 1963 Rookie of the Year; a year later, he became the first Met elected to a starting berth in the All-Star Game .... Although he never reached 60 RBIs and closed with a lifetime batting average of .261, Kranepool spent his entire 18-year career with the Mets.

The most immediate results of the team's move from the glum Polo Grounds to Shea Stadium in 1964 was a dramatic hike in attendance. After two seasons of barely missing and barely topping the one-million mark, the team reeled off annual attendance totals of 1.7, 1.7, 1.9, 1.5, and 1.7 million in its first five years in the new Queens facility.

What the fans mainly got for their money were memorable games that the Mets, for all their David-versus-Goliath valor, still ended up losing. In 1964, for instance, the team observed Memorial Day by battling the Giants in a record-breaking 10-hour doubleheader that featured a 24-inning nightcap during which the Mets pulled off a triple play, San Francisco's Willie Mays was forced to play shortstop, and Gaylord Perry pitched 10 shutout innings thanks to his first big league use of a spitball. Three weeks later, on Father's Day, 27 Mets trooped to the plate and then back to the bench again as Philadelphia's Jim Bunning tossed a perfect game against them.

The out-with-the-old-in-with-the-new attitude spurred by the team's shift to Shea Stadium came close to costing Stengel his position as manager for the 1965 season. After still another cellar finish, the press stepped up its quotes from the usual anonymous players accusing him of falling asleep on the bench during games and no longer even being able to identify his personnel .... Stengel's ties to the team were unraveled, then severed altogether, by two accidents during the 1965 season. In the first one, on May 10, the 74-year-old manager fractured his wrist in a fall at West Point, where the Mets had gone to play an exhibition game. The injury forced him to turn over the club, at least temporarily, to coach Wes Westrum. Then, in late July, during a banquet held to honor the former stars who would appear the following day at an old-timers' game, another fall fractured his hip ....[W]ith explicit blessings from Stengel and despite previous indications that [Yogi] Berra would be tapped as a successor, coach Wes Westrum was given a contract as the new manager. It was under Westrum in 1966 that the team avoided 100 losses for the first time and even got out of the cellar past the Cubs.

Because of the improved showing, 1967 was the first season in which the hopes of the New Breed did not appear completely unrealistic. They did, however, prove groundless when the team slipped back to last place with 101 losses. The responsibility for the reversal was equally shared among the players, the manager, the front office, and the ownership -- and with important ramifications for the team that was to excite the nation only a couple of years later.

On the field, the 1967 team's only effective offense came from the leg-sore Tommy Davis, who batted .302 with 16 homers and 73 RBIs after being obtained in a trade with the Dodgers for Hunt. On the bench, Westrum managed with a defensiveness that observers attributed to his fears he would be replaced any day by the far more popular Berra. Up in the general manager's office, [Bing] Devine, who had ... [replaced] Weiss before the start of the season, behaved as though his only priority was to put a personal imprint on the team; at one time or another during the season, 27 different pitchers and 27 different position players wore the Mets uniform ....

The first to crack was Westrum who, with less than two weeks to go in the season, asked for a contract renewal, got turned down, and resigned on the spot. Grant immediately ... [ordered] Devine to get the one and only man he wanted as the next manager -- the then-skipper of the Washington Senators, original Met [Gil] Hodges....

In raw numbers, the 1968 accomplishments of the Mets were modest. At the end of the season, they found themselves out of the cellar and 12 games better off than in 1967, but they were still 16 games below a break-even mark. On the plus side, however, was the near-emergence of a nucleus of young players who were to make the team competitive for years to come. These included catcher Jerry Grote, shortstop Bud Harrelson, outfielder Cleon Jones, and pitchers Jerry Koosman (19 wins in 1968), Nolan Ryan, and Jim McAndrew. Most of all, there was the righthander who was to become known as The Franchise, Tom Seaver.

Seaver came to the Mets through the sheerest luck -- via a special lottery drawing held by the commissioner's office after his earlier signing by the Braves had been ruled as being in violation of the amateur drafting rules. As soon as the Mets were awarded first negotiation rights ... the team signed the Fresno native to a $50,000 bonus contract and installed him in the rotation as the number two starter behind Jack Fisher in May of 1967. Seaver responded with the most wins (16) ever by a Mets pitcher and surprised nobody by being voted NL Rookie of the Year. In 1968, he won another 16 games and struck out more than 200 batters for the first of nine consecutive seasons .... Seaver became the franchise's first Hall of Famer ....

.... [I]n May, the Mets ... obtained power-hitting first baseman Donn Clendenon from Montreal in exchange for four minor league prospects. Even with Clendenon's bat and Hodges' clear determination to make the clownish Mets of Stengel a thing of the remote past, there was little reason to think the club would mark its first year of divisional play by marching on to a World Series championship .... As it turned out, almost all the ... players had career or near-career years; the shortstop Harrelson emerged as one of the league's deftest fielders, catcher Grote shone as a defensive backstop at least the equal of Cincinnati's Johnny Bench, left fielder Jones batted .340, and center fielder Tommie Agee overcame a horrendous season in 1968 to lead the club offensively with 26 homers and 76 RBIs. But both on and off the mound, it was the pitchers -- and primarily Seaver -- who proved to be the key .... [T]he righthander [had] the first of his three Cy Young Award seasons, posting a 25-7 record and an ERA of 2.21.

The drive to the East Division title remained highly improbable as late as the second week of August, when the team was still behind the first-place Cubs by 9.5 games. By winning 38 of its next 49 games, however, the club ended up with its own eight-game lead over Chicago and built the legend of the Miracle Mets. Down the stretch, omen seekers were more than satisfied by one game against the Cubs in which a black cat strolled out of the stands at Shea Stadium and scampered over to vex Chicago manager Leo Durocher, and by another game in which St. Louis ace Steve Carlton struck out a record 19 batters -- but still lost to the Mets on two home runs by right fielder Ron Swoboda. Another turning point, according to many of the Mets themselves, was a midseason game in which Hodges called time to take a long stroll out to left field and order Jones to accompany him back to the dugout for being less than energetic in his defensive play.

In their first taste of postseason competition, the Mets resorted to hitting rather than pitching to sweep the Braves in the League Championship Series. In the World Series against heavily favored Baltimore, they fell back on pitching, the timely slugging of Clendenon and second baseman Al Weis, and the spectacular outfield defense of Agee and Swoboda to win four out of five against the Orioles. New York was the first expansion team to take a world championship, and would continue to stand alone in that category until the Kansas City Royals defeated the Cardinals 16 years later.

-- Donald Dewey & Nicholas Acocella

Total Ballclubs

2nd INNING

The Baseball Hotel

By the winter of 1988, the eight-story building in Boston's Kenmore Square, on the corner of Kenmore Street and Commonwealth Avenue, housed a bank, offices, and apartments for the elderly. In an earlier incarantion, 490 Commonwealth Avenue was the Hotel Kenmore, the hub of Boston baseball.

Opened in spring 1926, the elegantly appointed hostelry eventually became headquarters for all fourteen teams that came to visit the Red Sox and Braves. It became known as the "Baseball Hotel" and catered to the special needs of the boys of summer. "Baseball players are wonderful guests," assistant manager Everett Kerr said in the summer of 1952. "But they can be superstitious. And they're moody."

Hired help was required to know the game thoroughly. Front-desk clerks had to be able to recognize and accommodate, say, Connie Mack if he showed up without a reservation. Bellhops and coffee-shop waitresses had to know who was in a slump in order to tiptoe around them. The staff was encouraged to listen to ball games over the radio as they worked.

After night games, the kitchen stayed open until 2:00 A.M. so the boys could grab a bite to eat before bed. Extra-long beds were supplied to taller players, such as Hank Greenberg and Ralph Kiner. Bathrooms were equipped with showerheads just like the ones in the ballpark clubhouses.

The place was rich with baseball lore. In the grille, Giants manager Leo Durocher had a lucky booth, the one he occupied while listening to the Dodgers lose a crucial game en route to the 1951 one-game playoff. When the Indians beat the Red Sox in the 1948 playoff, Cleveland owner Bill Veeck threw a party at the Kenmore that legend says lasted two days. Brooklyn shortstop Pee Wee Reese spent hours on Commonwealth Avenue feeding sugar cubes to the mounted policeman's horse. At one sitting in the dining room, Cardinals slugger Stan Musial consumed six lobsters. The place was rich with baseball lore. In the grille, Giants manager Leo Durocher had a lucky booth, the one he occupied while listening to the Dodgers lose a crucial game en route to the 1951 one-game playoff. When the Indians beat the Red Sox in the 1948 playoff, Cleveland owner Bill Veeck threw a party at the Kenmore that legend says lasted two days. Brooklyn shortstop Pee Wee Reese spent hours on Commonwealth Avenue feeding sugar cubes to the mounted policeman's horse. At one sitting in the dining room, Cardinals slugger Stan Musial consumed six lobsters.Joe McCarthy quit as Yankees manager, Bill Dickey was fired as Yankees manager, and shortstop Rabbit Maranville retired from the Braves at the Kenmore. In the lobby in the spring of 1947, Detroit catcher Birdie Tebbetts was traded to the Red Sox for catcher Hal Wagner. House detectives were routinely stationed outside the room of a player known to fall asleep while smoking cigars. In the spring of 1943, Casey Stengel walked out of the Kenmore at 2:00 A.M. and was hit by a cab.

When the Braves left Boston for Milwaukee before the 1953 season, the Kenmore's baseball business was halved. In the spring of 1965, the hotel was closed and the building was sold. From the rooftop boxes at Fenway Park in 1991, fans can look up from the ball game, see the old hotel's mansard roof and dormer windows, and wonder about the old ballplayers who used to throw them open in the morning, breathe in deep, and look forward to a coffee-shop breakfast and a ball game.

-- David Cataneo

Baseball Legends and Lore

3rd INNING

A Baseball Game in 1901

[What follows is the account of a baseball game between the Brooklyn Dodgers and Boston Braves as published in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle on Wednesday, 1 May 1901...]

One of those ideal games of base ball, which keeps the cranks up to the top notch of enthusiasm, was played at Washington Park yesterday, the Brooklyns winning out a sensational victory by the close score of 2 to 1 ....

It was a pitchers battle from start to finish, with honors about equally divided between Donovan and Willis, although the Brooklyn star allowed fewer hits than the tall, slim young man who had dished up a remarkable assortment of curves for Boston during a number of years.

The visitors got one run off Donovan in the first, and as the game progressed ... that single run assumed huge proportions.

Not until the sixth did the locals get a man as far as second base. In fact, not until then did the Brooklyns have even the slightest chance to score. In that inning three men were left on the bases, and the hopes of tieing [sic] were apparently dashed to earth for good.

But the strain told on the Bostons ... and in the seventh a couple of errors in succession by Long, added to Daly's splendid base running and a timely single from the bat of Lefty Davis brought in the run that placed the teams on even terms. But the strain told on the Bostons ... and in the seventh a couple of errors in succession by Long, added to Daly's splendid base running and a timely single from the bat of Lefty Davis brought in the run that placed the teams on even terms.The ninth saw the tables turned drastically .... Dahlen, who had been robbed of two good hits by the phenomenal fielding of Billy Hamilton early in the struggle, opened the inning with a two-bagger to left, went to third on a well-timed sacrifice by McGuire and scored the winning run when Donovan smashed out a hot drive that caromed safely off Willis' almost invisible anatomy.

There was an afterpiece to the game that added zest to the show .... The Boston players had kicked hard on several occasions against decisions by Umpire Colgan, particularly in the ninth, when he called Lowe out at second on a steal, and they made several unpleasant remarks as the official wended his way into the grand stand.

Several of the bleacherites began the demonstration by jumping into the field and calling the umpire "robber," and the visiting players took the cue.

"Home umpire, home umpire!" shouted Captain Long as he walked across the field, intimating that Colgan favored the Brooklyns.

"You ain't got sand enough to stand up and take your medicine," chimed in Billy Hamilton, who had had frequent arguments with Colgan over strikes.

The umpire paid no attention ... but kept on his way and soon disappeared into the dressing room. And the Boston players walked off apparently satisfied ....

And yet Colgan was impartial in his distribution of bad decisions, for he gave the home team as rough a deal as he administered to the visitors .... Donovan was surely safe at first in the sixth, he beating out a hit to Long which the latter fumbled. Had Colgan seen the play properly the game would have been won then and there, for Keeler eventually reached first on Tenney's fumble, Sheckard hit safely to right and Kelley got a free pass which, with McCreery's fly to Hamilton, would have brought in at least two runs.

Donovan was very much in the game. He not only brought in the winning run with a timely hit, but worked himself into fame by pitching remarkable ball. Only five hits were made off his delivery, which was up to McGinnity's form of last year, while he placed six strikeouts to his credit, three of them in one inning.

....Dahlen was again in evidence with six good plays .... McGuire caught well, beside nailing two ambitious base runners, and Keeler and McCreery divided the honors in the outfield. Kelley also gave a splendid exhibition at first.

For Boston, Hamilton easily walked away with the star achievements of the day. He very nearly equaled McCreery's record on Monday, making seven put-outs. Two of them, both off Dahlen, were remarkable .... [One] was a clean line drive straight toward the center field fence. Billy had to run full tilt at right angles and grabbed the ball on the jump. Against any other fielder the hit would have been good for a homer.

-- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle

May 1, 1901

Brooklyn Dodgers mentioned: Deacon McGuire c, Joe Kelley 1b, Tom Daly 2b, Bill Dahlen ss, Willie Keeler of, Jimmy Sheckard of, Tom McCreery of, "Wild" Bill Donovan p

Boston Braves mentioned: Fred Tenney 1b, Bobby Lowe 3b, Billy Hamilton of, Herman Long ss, Vic Willis p

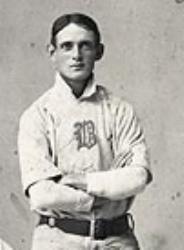

IMAGE: Boston's Herman Long

4th INNING

Minor Leagues Stars

Minor-league audiences have witnessed some phenomenal performances over the years. In 1954, Joe Bauman, a first baseman with Roswell, hit 72 home runs to establish a minor-league baseball record that still stands. Tony Lazzeri, who would eventually star at second base for the New York Yankees, drove in 222 runs for San Francisco of the Pacific Coast League in 1925 (his team played 197 games that year). In 1922, pitcher Joe Boehler won 38 games for Tulsa of the Western League. In 1951, Willie Mays compiled an astounding .477 batting average over 35 games for the Minneapolis Millers. Mays was promptly summoned by his parent club, the New York Giants, and never spent another day in the minors.

Minor-league slugger Joe Bauman

Some players' lifetime totals are equally staggering. Hector Espino, a slugging first baseman, hit a minor-league career record 484 home runs, primarily for teams in the Mexican League. Bill Thomas won 383 games while pitching for various teams and leagues. Right-hander Frank Shellenback holds the Pacific Coast League career wins record with 295. Because he relied primarily on a spitball, Shellenback's major-league prospects were shattered when the major-league owners banned that slippery pitch. Ox Eckhardt spent parts of 13 seasons with various minor-league clubs; he retired with the highest career batting average in minor-league history -- a dazzling .367.

Buzz Arlett won 108 games in his first six minor-league seasons (1918-23). He won 29 games while pitching for Oakland in the Pacific Coast League in 1920. He also enjoyed two 25-win seasons. However, after hurting his arm, he switched to the outfield and hit 432 career homers. In 1931, the 32-year-old Arlett earned a spot on the Philadelphia Phillies of the National League. In his only major-league season, he hit .313 with 18 home runs and 72 runs batted in. Despite this fine showing, the Phillies released him after the season and no other major-league team picked him up. (Apparently, Arlett was considered a dreadful fielder, though many minor-league historians claim he was an adequate glove man.) And special note should be taken of left-hander George Brunet. Between the majors and minors, he pitched in professional ball for 33 years (1953-1985). In his final season, Brunet compiled a miniscule 1.94 earned run average in the heavy-hitting Mexican League; he was 48 years old.

The minors have also showcased their share of legendary teams. The best of these may be the 1937 Newark Bears, a New York yankee affiliate that featured such future major-league stars as second baseman Joe Gordon (an eventual American League MVP), outfielder Charlie "King Kong" Keller, first baseman George McQuinn, and pitcher Atley Donald. This group won the International League pennant by 25-1/2 games with a 109-41 record.

Joe Morgan with Richard Lally

Baseball for Dummies

5th INNING

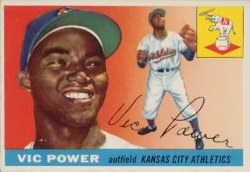

Vic Power: From Puerto Rico to Yankee Stadium (Part 2)

After the good year I had in Syracuse in 1951, I should have been brought up by the Yankees. But instead they sent me to the Kansas City Blues in the American Association. I had a great year in 1952. I batted .331 with 40 doubles, 17 triples, 16 home runs, and 109 RBIs .... After the good year I had in Syracuse in 1951, I should have been brought up by the Yankees. But instead they sent me to the Kansas City Blues in the American Association. I had a great year in 1952. I batted .331 with 40 doubles, 17 triples, 16 home runs, and 109 RBIs .... After my great season at Kansas City in 1952, I hoped that the Yankees would finally bring me up. But they decided to keep me in Kansas City for another year .... I lost two prime years in my major league career because the Yankees were reluctant to make me their first black player. In the winter, Jackie Robinson went on television in New York and criticized the Yankees for not bringing up a black player. They brought up my white teammates, including Bob Cerv and Andy Carey, but not me. I think they were waiting for my skin to turn white. Blacks and Puerto Ricans picketed Yankee Stadium so they would bring me up, and the Yankees got mad at me. They kept making excuses. They'd say I didn't prove I could hit major league pitching. But they wouldn't even invite me to spring training so I could face big league pitchers. Meanwhile they were saying how they wanted a "decent" black to be their first ....

Maybe the Yankees didn't want a black player who would openly date light-skinned women, or who would respond with his fists when white pitchers threw beanballs at him. I was the only black on Kansas City, and every time one of my teammates would homer, the pitcher would throw at my head. There weren't helmets in those days, so I had to rely on my reflexes and my fists. I had to protect myself. I had a temper and got into some brutal fights. Being Puerto Rican, I would fight anybody, but I wasn't a troublemaker. We'd play games in Arkansas, Louisiana, and Mississippi, and the people would call me names, but I wouldn't respond ....

In 1953 I had another great year. I led the league with a .349 average, had 217 hits, 115 runs, 93 RBIs. Now everybody knew about me. I figured the Yankees couldn't ignore me any longer. Elston Howard was my roommate on the Blues. He wasn't my competition to be the Yankees' first black. He wasn't a star. He was a conservative player, and his numbers weren't too good. The Yankees couldn't justify picking him as their first black as long as I was in their organization.

In December I was in New Orleans trying to ship my car to Puerto Rico when I looked down at a newspaper on the floor and discovered that I had been traded to the Philadelphia Athletics. That's how I found out I was no longer a Yankee. (In 1955, the Yankees would bring up Elston Howard as their first black player.)

I didn't care too much because I just wanted to play in the majors. I would have been a big attraction in New York because of all the blacks and Puerto Ricans, but the Yankees didn't want me. Or maybe they didn't want blacks and Puerto Ricans coming to Yankee Stadium. In the mid-'50s, the Puerto Rican fans would hold a day for me in Yankee Stadium. They had a trophy to give me before the game, but the Yankee organization wouldn't let them give it to me at home plate, so they held the ceremony in the stands. That game I hit 2 homers, one against each pole. I would always hit my best against the Yankees.

--Vic Power

We Played the Game

See Issue 16, 6th Inning, for Part 1 -- ed.

6th INNING

Stats: Games

1. Pete Rose 3,562 ... 2. Carl Yastrzemski 3,308 ... 3. Hank Aaron 3.298 ... 4. Ty Cobb 3,035 ... 5. Stan Musial 3,026 ... 6. Willie Mays 2,992 ... 7. Dave Winfield 2,973 ... 8. Eddie Murray 2,971 ... 9. Rusty Staub 2,951 ... 10. Brooks Robinson 2,896 ... 11. Robin Yount 2,856 ... 12. Al Kaline 2,834 ... 13. Eddie Collins 2,826 ... 14. Reggie Jackson 2,820 ... 15. Frank Robinson 2,808 ... 16. Honus Wagner 2,792 ... 17. Tris Speaker 2,789 ... 18. Tony Perez 2,777 ... 19. Mel Ott 2,730 ... 20. George Brett 2,707 ... 21. Craig Nettles 2,700 ... 22. Darrell Evans 2,687 ... 23. Rabbit Maranville 2,670 ... 24. Joe Morgan 2,649 ... 25. Andre Dawson 2,627 ... 26. Lou Brock 2,616 ... 27. Dwight Evans 2,606 ... 28. Luis Aparicio 2,599 ... 29. Willie McCovey 2,588 ... 30. Ozzie Smith 2,573 ... 31. Paul Waner 2,549 ... 32. Ernie Banks 2,538 ... 33. Cap Anson 2,523 ... 34. Sam Crawford 2,517 ... 35. Bill Buckner 2,517 ... 36. Babe Ruth 2,503 ... 37. Carlton Fisk 2,499 ... 38. Dave Concepcion 2,488 ... 39. Billy Williams 2,488 ... 40. Nap Lajoie 2,480 ... 41. Max Carey 2,476 ... 42. Vada Pinson 2,469 ... 43. Rod Carew 2,469 ... 44. Dave Parker 2,466 ... 45. Ted Simmons 2,456 ... 46. Bill Dahlen 2,443 ... 47. Ron Fairly 2,442 ... 48. Harmon Killebrew 2,435 ... 49. Roberto Clemente 2,433 ... 50. Willie Davis 2,429 1. Pete Rose 3,562 ... 2. Carl Yastrzemski 3,308 ... 3. Hank Aaron 3.298 ... 4. Ty Cobb 3,035 ... 5. Stan Musial 3,026 ... 6. Willie Mays 2,992 ... 7. Dave Winfield 2,973 ... 8. Eddie Murray 2,971 ... 9. Rusty Staub 2,951 ... 10. Brooks Robinson 2,896 ... 11. Robin Yount 2,856 ... 12. Al Kaline 2,834 ... 13. Eddie Collins 2,826 ... 14. Reggie Jackson 2,820 ... 15. Frank Robinson 2,808 ... 16. Honus Wagner 2,792 ... 17. Tris Speaker 2,789 ... 18. Tony Perez 2,777 ... 19. Mel Ott 2,730 ... 20. George Brett 2,707 ... 21. Craig Nettles 2,700 ... 22. Darrell Evans 2,687 ... 23. Rabbit Maranville 2,670 ... 24. Joe Morgan 2,649 ... 25. Andre Dawson 2,627 ... 26. Lou Brock 2,616 ... 27. Dwight Evans 2,606 ... 28. Luis Aparicio 2,599 ... 29. Willie McCovey 2,588 ... 30. Ozzie Smith 2,573 ... 31. Paul Waner 2,549 ... 32. Ernie Banks 2,538 ... 33. Cap Anson 2,523 ... 34. Sam Crawford 2,517 ... 35. Bill Buckner 2,517 ... 36. Babe Ruth 2,503 ... 37. Carlton Fisk 2,499 ... 38. Dave Concepcion 2,488 ... 39. Billy Williams 2,488 ... 40. Nap Lajoie 2,480 ... 41. Max Carey 2,476 ... 42. Vada Pinson 2,469 ... 43. Rod Carew 2,469 ... 44. Dave Parker 2,466 ... 45. Ted Simmons 2,456 ... 46. Bill Dahlen 2,443 ... 47. Ron Fairly 2,442 ... 48. Harmon Killebrew 2,435 ... 49. Roberto Clemente 2,433 ... 50. Willie Davis 2,4297th INNING

Year in Review: 1916

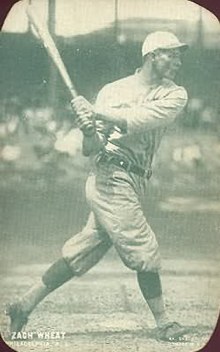

In 1916 Brooklyn won its first pennant since the days of Ned Hanlon in 1900. Fan favorite Zach Wheat batted .312 with 32 doubles and 13 triples and led the NL in slugging average at .461. Wheat, Jake Daubert (whose .316 batting mark was second in the league to Hal Chase's .339), and outfielder Hy Myers (who slugged 14 triples), combined to give Brooklyn the league's second-best offense; only the Giants scored more runs, 597 to 585. Carried by Pete Alexander's 33 wins and a league-low 1.55 ERA, second -place Philadelphia finished 2-1/2 games off the pace; Boston came in 4 games back. In 1916 Brooklyn won its first pennant since the days of Ned Hanlon in 1900. Fan favorite Zach Wheat batted .312 with 32 doubles and 13 triples and led the NL in slugging average at .461. Wheat, Jake Daubert (whose .316 batting mark was second in the league to Hal Chase's .339), and outfielder Hy Myers (who slugged 14 triples), combined to give Brooklyn the league's second-best offense; only the Giants scored more runs, 597 to 585. Carried by Pete Alexander's 33 wins and a league-low 1.55 ERA, second -place Philadelphia finished 2-1/2 games off the pace; Boston came in 4 games back.The NL's strangest team was undoubtedly John McGraw's chameleon-like Giants. They opened the season with eight straight home losses, followed with a 17-game winning streak on the road, then slumped. Trying to rebuild in midseason, McGraw put young outfielder Dave Robertson into the lineup, released catcher Chief Meyers, traded Fred Merkle to Brooklyn, and swapped Larry Doyle to Chicago for legendary hothead Heinie Zimmerman. McGraw sent the great Christy Mathewson to Cincinnati to take over for player/manager Buck Herzog, and in return acquired Herzog and Red Killefer. Federal League star Benny Kauff became an every-day outfielder.

The result of all this shuffling was that the Giants went on an all-time record 26-game winning streak -- this time, all at home -- but played badly enough before and after the streak that they came in fourth, with an 86-66 record. Hall of Famer Rogers Hornsby played his first full season with St. Louis, batting .313. In Chicago, dead-ball great Three Finger Brown recorded his 239th career win against only 130 losses; his lifetime ERA over 14 seasons was 2.06, the third-lowest in history.

Boston overcame the sale of Tris Speaker to Cleveland after a salary dispute to repeat, finishing 2 games ahead of Chicago with a 91-63 record in the American League. This year was almost the same story as 1915 for the Red Sox: Their sixth-best offense was carried by an awesome pitching staff that included emerging ace Babe Ruth, who won 23 games and the ERA title at 1.75. Dutch Leonard, Rube Foster, and underhand power pitcher Carl Mays were also part of a Sox staff that led the AL in shutouts with 24. Boston was bested in team ERA only by a Chicago staff of Eddie Cicotte (ERA runner-up at 1.78), Red Farber (who had an ERA of 2.02), Reb Russell, and young Lefty Williams.

Ty Cobb's Tigers finished third, 4 games out, as Cobb led the AL in stolen bases with 68 and runs with 113; for the first time in the past ten years, however, Cobb lost the batting title. He was beaten out by Speaker, who outhit him .386 to .371 and led the league in hits with 211, doubles with 41, on-base average at .470, and slugging average at .502. Joe Jackson, traded before the season from Cleveland to the White Sox, was third in the loop in hitting at .341 and first in triples at 21.

-- David Nemec, et al.

The Baseball Chronicle

NL: Brooklyn, 94-60 ...Philadelphia, 91-62 ... Boston, 89-63 ... New York, 86-66 ... Chicago, 67-86 ... Pittsburgh, 65-89 ... St. Louis, 60-93 ... Cincinnati, 60-93

AL: Boston, 91-63 ... Chicago, 89-65 ... Detroit, 87-67 ... New York, 80-74 ... St. Louis, 79-75 ... Cleveland, 77-77 ... Washington, 76-77 ... Philadelphia, 36-117

8th INNING

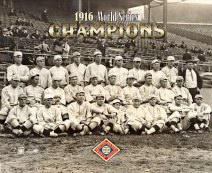

1916 World Series

Boston Red Sox (4) v Brooklyn Robins (1)

October 7-12

Braves Field (Boston), Ebbets Field (Brooklyn)

The 1916 World Series was a reprise of 1915, as Boston's 1.47 ERA pitching proved too strong for the National League lineup (Brooklyn logged a .200 batting average; Boston posted a .238 average against Brooklyn's 3.04 ERA). In Ernie Shore's 6-5 game one victory over Rube Marquard, Mays executed the last out in relief in the ninth to halt Brooklyn, which had racked up five runs and had one more on base. Boston finally pulled out a 2-1 win in game two -- after Ruth and Sherry Smith went at it for 14 innings -- on a Del Gainor pinch single that brought in Mike McNally. Jeff Pfeffer stepped in for Jack Coombs in the seventh inning of game three-- and retired eight men --- for Brooklyn's sole triumph, a 4-3 game. (Nemec, et al., The Baseball Chronicle) The 1916 World Series was a reprise of 1915, as Boston's 1.47 ERA pitching proved too strong for the National League lineup (Brooklyn logged a .200 batting average; Boston posted a .238 average against Brooklyn's 3.04 ERA). In Ernie Shore's 6-5 game one victory over Rube Marquard, Mays executed the last out in relief in the ninth to halt Brooklyn, which had racked up five runs and had one more on base. Boston finally pulled out a 2-1 win in game two -- after Ruth and Sherry Smith went at it for 14 innings -- on a Del Gainor pinch single that brought in Mike McNally. Jeff Pfeffer stepped in for Jack Coombs in the seventh inning of game three-- and retired eight men --- for Brooklyn's sole triumph, a 4-3 game. (Nemec, et al., The Baseball Chronicle)Game 1: Boston 6, Brooklyn 5

Game 2: Boston 2, Brooklyn 1

Game 3: Brooklyn 4, Boston 3

Game 4: Boston 6, Brooklyn 2

Game 5: Boston 4, Brooklyn 1

BOSTON: Hick Cady (c), Bill Carrigan (c), Rube Foster (p), Del Gainor (1b), Larry Gardner (3b), Olaf Henriksen (ph), Dick Hoblitzel (1b), Harry Hooper (of), Hal Janvrin (ss), Dutch Leonard (p), Duffy Lewis (of), Carl Mays (p), Mike McNally (pr), Babe Ruth (ph), Everett Scott (ss), Ernie Shore (p), Chick Shorten (of), Pinch Thomas (c), Tilly Walker (of), Jimmy Walsh (of). Mgr: Bill Carrigan

BROOKLYN: Larry Cheney (p), Jack Coombs (p), George Cutshaw (2b), Jack Daubert (1b), Wheezer Dell (p), Gus Getz (ph), Jimmy Johnston (of), Rube Marquand (p), Fred Merkle (1b), Chief Meyers (c), Otto Miller (c), Mike Mowrey (3b), Hy Myers (of), Ivy Olson (ss), Ollie O'Mara (ph), Jeff Pfeffer (p), Nap Rucker (p), Sherry Smith (p), Casey Stengel (of), Zach Wheat (of). Mgr: Wilbert Robinson

Babe Ruth pitched a 14-inning complete game in Game 2, allowing one run on six hits while striking out three. That one run was an inside-the-park homer by Hy Myers.

9th INNING

Player Profile: Casey Stengel

Full name: Charles Dillon Stengel

Nickname: Old Perfessor

Born: July 30, 1890 (Kansas City, MO)

Died: September 29, 1975 (Glendale, CA)

ML Debut: September 17, 1912

Final Game: May 19, 1925

Bats: Left Throws: Left

5 '11" 175

Hall of Fame: 1966 (Veterans Committee)

Charles Dillon Stengel was born in Kansas City in 1890, or maybe 1889, or possibly even earlier, though no one knows for sure. After graduating from high school he enrolled in Western Dental College in Kansas City for two and a half years, but an Aurora, Illinois, professional team scouted and signed him, and he never did complete his studies. While playing for Aurora, Stengel was discovered by a Brooklyn Dodger scout, and after the Dodgers bought him, he joined the team a year later in 1912. He was a regular Dodger outfielder for the next five years. Charles Dillon Stengel was born in Kansas City in 1890, or maybe 1889, or possibly even earlier, though no one knows for sure. After graduating from high school he enrolled in Western Dental College in Kansas City for two and a half years, but an Aurora, Illinois, professional team scouted and signed him, and he never did complete his studies. While playing for Aurora, Stengel was discovered by a Brooklyn Dodger scout, and after the Dodgers bought him, he joined the team a year later in 1912. He was a regular Dodger outfielder for the next five years. ....[T]hough Stengel preferred to spend his evenings on the town rather than keeping minister's hours, the rowdy outfielder always hustled and showed great desire on the field, developing an excellent reputation as an entertaining player. Some of his performances are now legendary. After he was traded from Brooklyn to Pittsburgh in 1917, he returned to Ebbets Field with the Pirates to play the Dodgers. Just before his first at bat, as the formerly Brooklyn faithful booed him as vociferously as they had once cheered him, Casey bowed low to the crowd and removed his cap, where underneath, perched on Stengel's head, was a sparrow, which flew away. Stengel had found the small bird dazed in the outfield during batting practice. He knew the Brooklyn fans were going to boo him, so he figured that if they were going to give him the bird, he would give them one in return.

Before another game with the Pirates, Stengel stood in center field, so rigid and stock-still that his manager ran out to find out what was wrong. Stengel told him that he was too weak to move because he wasn't getting paid enough to eat.

On to the Philadelphia Phillies in 1920, he was traded early in 1921 to the New York Giants, where he played under the legendary John McGraw .... Stengel, a lifetime .284 hitter during his fourteen-year playing career, batted .368 in 1922 and .339 in 1923 under McGraw's platoon system, and in the 1923 world series [he] hit two home runs to defeat the Yankees. Rounding the bases after hitting one of them, Stengel is remembered for giving the Yankee bench the finger, enraging Yankee owner Jake Ruppert .... Stengel finished his major league career in 1925 and retired to become the president, manager, and right fielder of the Worcester, Massachusetts, team in the Eastern League. At the end of 1925 Stengel, unhappy there, made history by giving himself his release as a player, firing himself as manager, and then quitting as president. He continued to manage in the minors until 1932 when he was hired as a Brooklyn coach, and in 1934 he was hired by the Dodgers to manage, inheriting a squad of mediocre bumblers. Stengel managed them for three seasons, finishing sixth, fifth, and seventh, and at the end of the third season, though he had another year left on a two-year contract, the Dodgers fired him, thus paying him in 1937 for not managing.

While with the Dodgers, Stengel made himself visible on the third-base coaching lines, delivering impromptu orations, conversing with the opposition, performing an occasional soft-shoe, and badgering the umpires, thus providing more entertainment than his players did. Stengel drove his players hard, and tried to instruct them, but most of them [did not] take advantage of his guidance. "Managing the team back then," Stengel would say years afterward, "was a tough business. Whenever I decided to release a guy, I always had his room searched first for a gun. You couldn't take any chances with some of them birds."

While managing Brooklyn, Stengel's most important personal gains were monetary. A teammate from Texas, Randy Moore, convinced him and three other teammates, Al Lopez, Van Lingo Mungo, and Johnny Cooney, to invest money in an east Texas oil field. Stengel's wells began gushing in 1941 and continued to do so for many lucrative years afterward. A Dodger stockholder also touted Stengel on a firm that was beginning to produce the new miracle drug called penicillin. He made a killing. He was becoming almost as wealthy as his wife, Edna, whose father was a successful banker.

.... [I]n 1938 [Stengel] signed a contract to manage the Boston Braves, another collection of ragtags and has-beens. Again he became the center of attraction in order to divert the minds of the fans from the poor quality of baseball being played. One dreary, rainy afternoon Stengel appeared on the field to exchange the lineup cards with the umpires wearing a raincoat and holding an umbrella in one hand and a lantern in the other. It was classic Stengel, and most of the writers loved him for his antics, his colorful stories, and his congeniality....

"For us," wrote Boston sportswriter Harold Kaese, "it was more fun losing with Stengel than winning with a hundred other managers." .... In his six years in Beantown, Stengel's Braves finished fifth, seventh, seventh, seventh, seventh, and sixth. When he was accidentally struck down by a cab in the spring of '43, breaking his leg and missing the first two months of the season, Boston Record writer Dave Egan voted the cabdriver "the man who did the most for Boston in 1943." At the end of the year Stengel was released, traveling to Milwaukee where he won the American Association pennant in '44, to Kansas City, where he impressed Yankee owner Del Webb, and to Oakland where he won the pennant in '48. [Yankee General Manager George] Weiss's first and only choice as a replacement for [Bucky] Harris was Stengel. This was a man Weiss trusted, a man he could work with, a man who would work with the younger players, and the perfect buffer to keep the press from the shy and private general manager.

-- Peter Golenbock

Dynasty: The New York Yankees, 1949-1964

Under [Stengel's] leadership from ... [f]rom 1949 to 1964, the [Yankees] won fourteen pennants and nine world championships. Only once in his dozen seasons did his teams win fewer than ninety games; his Yankee career managing record was 1,149-696, a winning percentage of .623.

.... Stengel's managerial method included riding players when they were doing well, panning them at other times. Platooning players became a Stengel managing trademark, as did using pinch hitters at unusual times.

.... "Sure he wasn't that young," [Bill] Skowron said. "But he knew and we knew what we had to do. He'd leave us alone when we were winning. He'd holler 'butcher boy' and 'don't swing too hard at ground balls' and 'don't beat yourselves.' But when he saw us making mistakes he'd get excited and do some yelling."

The Yankees took the 1958 pennant by ten games. The 1959 Yankees finished in third place, their low point in Stengel's time as manager. There were some who thought it was the beginning of the end. Nearing seventy, impatient, Casey made moves in games that seemed highly unorthodox even for him....

Inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1966, Casey Stengel was fittingly selected as Baseball's Greatest Manager during the sport's centennial.

"Casey was a great, great manager, probably the greatest of all," mused Jerry Coleman. "He understood his players, what they could do and what they couldn't do. He understood the front office -- what they wanted from him. He understood the media and that was vital in New York. He understood the fans -- he was a great communicator. You don't forget a man like Casey."

-- Harvey Frommer

A Yankee Century

.... For several years Webb and Topping were anxious to replace [Stengel] before some other club snatched Ralph Houk away from the New York affiliate in Denver. Their opportunity came after the team's 1960 World Series loss to Pittsburgh, when Stengel was criticized heavily for getting only two starts out of his ace [Whitey] Ford and for getting Ralph Terry up in the bullpen four times before finally calling him in to serve up Bill Mazeroski's decisive home run in the final game. Two days after the Series Stengel officially "retired," while putting up no pretense that it had been his idea. "I'll never make the mistake of being 70 again," he complained.

Two years later [George] Weiss, in his new role as president of the embryonic Mets, hired Stengel to manage the expansion team, making him the only one to wear the uniforms of all four 20th-century New York clubs. Stengel's task was less to direct the sorry collection of veterans that compiled one of the worst records in the history of baseball than to promote his Amazin' Mets has better entertainment than the Bronx club he had just left. For nearly four years hardly a day went by without the sports page reporting some bizarre or bizarrely stated observation from him on the miserable state of his squad. The brilliance of his public relations performance endeared the incompetent Mets to The New Breed fans, who relished the incompetence almost as much as its promotion. "Can't anybody here play this game?" became as much a trademark Stengel line as "You could look it up." He ended up wisecracking his way through three 10th-place finishes and part of another.

....In 1965 a broken wrist forced the 74-year-old manager to turn the club over to coach Wes Westrum temporarily. Then in late July, after a banquet the night before an Old Timers Game, another fall fractured his hip. Everybody but the Mets players were sorry about the announcement of his retirement. Stengel lived for more than a decade after returning to his California home in Glendale. The inscription on his tombstone is one of his most quoted lines: "There comes a time in every man's life, and I've had plenty of them."

-- Dewey & Acocella

The New Biographical History of Baseball

EXTRA INNINGS

They Played the Game

Wade Boggs

(1982-99)

Hall of Famer Boggs won the AL batting title five times (1983, 1985, 1986, 1987, 1988) and broke Al Simmons' mark of five consecutive seasons with 200 or more hits by doing it seven straight times between 1983 and 1989.

BORN 6.15.58, Omaha, NE .328, 118, 1014

All-Star 1985, 1986, 1987, 1988, 1989, 1990, 1991, 1992, 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996

Gold Glove 1994, 1995 Silver Slugger 1983, 1986, 1987, 1988, 1989, 1991, 1993, 1994

Joe Carter

(1983-98)

Carter was the first player to start at three different positions in three straight World Series games when, in 1992, he played left field, right field and first base for Toronto.

BORN 3.7.60, Oklahoma City, OK .259, 396, 1445

All-Star 1991, 1992, 1993, 1994, 1996 Silver Slugger 1991, 1992

Henry Chadwick

Chadwick didn't play the game, but he contributed greatly to it. The British-born journalist did much to popularize the sport in the 19th century. He introduced statistical benchmarks such as the batting average, and the newspaper box score. He was referred to, at the time, as the "Father of Baseball" and was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1938, the only sportswriter to be so honored

Joe Start

(1871-86)

One of the game's best first basemen for two decades. Start is credited with being the player who ended the amazing winning streak of the Cincinnati Red Stockings on June 14, 1870 while playing for the Brooklyn Athletics. Start retired with a .300 batting average and numerous records.

"Old Reliable" BORN 10.14.1842, New York, NY .299, 15, 544

Joe Sullivan

(1893-96)

Washington Senators shortstop Sullivan has the dubious distinction of being the last major league player with 100 or more errors in a season. He collected 102 in 1893.

BORN 1.1.1870 (Charleston, MA) .299, 11, 227

THIS MATERIAL IS REPRODUCED FOR NON-PROFIT EDUCATIONAL AND SCHOLARLY PURPOSES ONLY, WHICH COMPLIES WITH THE DOCTRINE OF FAIR USE AS EXPRESSED IN THE COPYRIGHT ACT OF 19 OCTOBER 1976, EFFECTIVE 1 JANUARY 1978 (TITLE 17 OF THE UNITED STATES CODE, PUBLIC LAW 94-553, 90 STAT. 2541.)

|