9 Innings 9 InningsA Baseball History Reader

J. Manning, Editor

|

Issue # 16: November 28, 2006

The Seattle Pilots ... The Oddest Game ... Ballplayers as Entertainers ... Instant Replay in Baseball? ... Vic Power: From Puerto Rico to Yankee Stadium ... Stats: 2006 MVPs ... Year in Review: 1915 ... The 1915 World Series ... Player Profile: Cap Anson ... Baseball Dictionary (ball boy - bang bang play)

|

"I don't care how long you've been around, you'll never see it all."

-- Bob Lemon

1st INNING

The Seattle Pilots

The Pilots were a bad idea whose time had come. Underfinanced in the boardroom, undertalented on the field, and under siege long after it had ceased to exist, the franchise proved profitable to few people outside of attorneys in several states and Ball Four author Jim Bouton. The Pilots were a bad idea whose time had come. Underfinanced in the boardroom, undertalented on the field, and under siege long after it had ceased to exist, the franchise proved profitable to few people outside of attorneys in several states and Ball Four author Jim Bouton.The expansion Pilots were created in December 1967 as part of the agreement between the American League and Missouri politicians that also sired the Kansas City Royals in return for allowing Charlie Finley's Athletics to migrate from Kansas City to Oakland. The $6-million admission tab (including expansion draft purchases and contributions to the players pension fund) was picked up by former Cleveland Indians owner and Reading Railroad chairman William Daley, who controlled 60 percent of the stock, and Pacific Coast League president Dewey Soriano, who with his brothers Max and Milton represented another 34 percent. Among the league conditions for awarding the franchise to Dewey and the Sorianos were the minor league Sicks Stadium would be enlarged to provide and temporary playing site, that Seattle voters would get behind a $40-million bond issue for building a domed facility, and that the owners would pay the Pacific Coast League $300,000 in indemnities for invading its territory. None of these conditions was met in the way the AL intended .... Although voters eventually endorsed the bond issue for what became the Kingdome, the project turned into an $80-million political football that was not pulled down in the end zone until after the Pilots had expired. As for the indemnities to the PCL, they were not paid off fully until Class A teams were back as the only baseball action in town.

With Daley anchored to Cleveland as an absentee owner, Soriano assumed the club presidency and appointed Marvin Miller as general manager .... The first player under contract was first baseman-outfielder Mike Hegan, acquired from the Yankees a couple of months before the October 1968 expansion draft. The club's first selections at the draft were slugging first baseman Don Mincher and speedster third baseman Tommy Harper. Other familiar names on the roster were Bouton, Tommy Davis, Diego Segui, Mike Marshall and Gary Bell It was Bell who, before 15,014, began the team's brief existence with a 10-hit shutout over Chicago on April 11, 1969.

For a couple of months the Pilots remained respectable, but then hit a summer skid that dropped them down to the cellar finish that had been predicted for them. The bright spots were Harper (a league-leading 73 steals), Mincher (25 homers and 78 RBIs), and Segui (12 wins and 12 saves). Although the 15,000 seats in Sicks Stadium made high attendance impossible, the final total of 677,944 was bigger than that registered by the White Sox, Indians, Padres and Phillies.

....Although Daley had gotten involved in the franchise in the first place because the Sorianos had been unable to find sufficient backing in Seattle, the AL continued to insist that it wanted to stay in the northwestern city. In the fall of 1969, even as Daley and the Sorianos were fielding offers from Lamar Hunt to buy the club and move it to Dallas and from a Milwaukee syndicate bent on purchasing the franchise for Wisconsin, league representatives met with Fred Danz, operator of a Washington theater chain, to see if he could keep the club where it was. They were so impressed with Danz that they voted conditional approval of his purchase -- only to discover that he didn't have the $10.5 million he claimed to have and that due notes from the Bank of California on Soriano's loans would have wiped out the money even if it had existed.

....When still another Seattle group headed by Edward Carlson ... was in the process of putting together a Seattle syndicate ... word leaked of a $13.5-million deal between Daley-Soriano and Milwaukee interests. In rapid succession, this produced local injunctions against letting the team leave Seattle, a countermove by the Sorianos in applying for bankruptcy protection, and another suit by Seattle citizen Alfred Schweppe demanding to know how bankruptcy could be granted to people who admitted that they would make more than one million dollars off the sale to Milwaukee. While all these legal duels went on, the other AL clubs had to put up $50,000 each to finance 1970 spring training for the Pilots and to pay off some of the franchise's most pressing debts. Finally, in late March ... a bankruptcy referee ruled that the sale of the club to Milwaukee was in order. The league had approved the transaction 24 hours before, so the referee's decision was the green light for the Milwaukee Brewers to succeed the Pilots.

The sale to Milwaukee created new problems for the league. As might have been expected, Washington's U.S. senators, Warren Magnusson and Henry Jackson, called for a congressional investigation of baseball's exemption from antitrust laws; equally predictably, they fell quiet as soon as the AL committed itself to putting a new franchise in Seattle sometime in the early 1970s. By the time the Mariners were actually created in 1977, both the city of Seattle and the state of Washington had filed lawsuits totaling some $32.5 million against the league.

Aside from the Mariners, the most notable result of the Daley-Soriano franchise was Bouton's book, which scandalized both players and the baseball establishment by naming names in a diaristic narrative of the three-quarters of a season that the righthander spent with the club. Commissioner Bowie Kuhn helped make the book a best-seller by summoning Bouton to his office and demanding that he make a public apology for it .... Much of the uproar over Ball Four was over its casual depiction of the sex-obsessed lives of big leaguers, especially while on the road; but it also unnerved front office executives with its specific instances of settling rosters through racial quotas and of management hypocrisy during contract negotiations....

-- Donald Dewey & Nicholas Acocella

Total Ballclubs

2nd INNING

The Oddest Game

[In September 1941, with Brooklyn and St. Louis locked in a tight pennant race, the Dodgers played] Cincinnati, and it was one of the oddest games ever played, a classic that turned into a farce. It began with an argument before the first pitch when [Dixie] Walker, leading off for Brooklyn, berated plate umpire Larry Goetz about something that had happened the day before. Goetz was a strong, capable, no-nonsense umpire who should be in the Hall of Fame, and he told Walker to stop yammering and to get in the batter's box and hit. Walker continued to jaw at him and Goetz motioned to the Cincinnati pitcher, Paul Derringer, to throw the ball, even though Walker was not in the batter's box. Derringer did and Goetz called it a strike. Walker telled and [Brooklyn manager Leo] Durocher charged from the dugout. Goetz motioned to Derringer to pitch again, but Durocher stood on home plate so that Derringer couldn't throw. When Leo, arguing with Goetz, moved away from the plate Derringer pitched again, but Goetz, busy with Durocher, didn't call that one. [In September 1941, with Brooklyn and St. Louis locked in a tight pennant race, the Dodgers played] Cincinnati, and it was one of the oddest games ever played, a classic that turned into a farce. It began with an argument before the first pitch when [Dixie] Walker, leading off for Brooklyn, berated plate umpire Larry Goetz about something that had happened the day before. Goetz was a strong, capable, no-nonsense umpire who should be in the Hall of Fame, and he told Walker to stop yammering and to get in the batter's box and hit. Walker continued to jaw at him and Goetz motioned to the Cincinnati pitcher, Paul Derringer, to throw the ball, even though Walker was not in the batter's box. Derringer did and Goetz called it a strike. Walker telled and [Brooklyn manager Leo] Durocher charged from the dugout. Goetz motioned to Derringer to pitch again, but Durocher stood on home plate so that Derringer couldn't throw. When Leo, arguing with Goetz, moved away from the plate Derringer pitched again, but Goetz, busy with Durocher, didn't call that one.The game got under way, went seventeen innings and was scoreless for the first sixteen. That must have seemed routine for Derringer, who had gone sixteen innings against the Dodgers in June before losing 2-1. This time he gave up fourteen hits and four walks in his sixteen scoreless innings, but the hits were all singles, and the Dodgers couldn't push a run across. They left seventeen men on base.

Johnny Allen pitched for the Dodgers, and he pitched well, too, better than Derringer, as a matter of fact, despite getting into a blistering argument with [Bill] McKechnie, the Reds' manager, whose calm, scholarly demeanor had earned him the nickname Deacon Bill. Coaching at third for his team, Deacon Bill kept complaining loudly that Allen was throwing spitters ....

Thus beleaguered, Allen pitched the game of his life. He gave up just one hit in the first nine innings and only six all told, three of them scratch singles to the infield. After fifteen innings Allen was exhausted, and when he reached base in the top of the sixteenth Durocher lifted him for a pinch runner.

Hugh Casey pitched the last of the sixteenth and retired the Reds without difficulty, and the game went to the top of the seventeenth, still 0-0. The umpires conferred. It was very dark, and ordinarily the game would have been called at that point. But the Cincinnati fans were yelling at them to let it continue, and because of the importance of the game in the pennant race, the umpires decided to let it go one more inning.

As though on cue [Pete] Reiser led off the top of the seventeenth by hitting a home run over the right-field fence to give the Dodgers a 1-0 lead. Disgusted, Derringer gave up singles to the next two hitters, and McKechnie replaced him with his best relief pitcher, Joe Beggs. By the time McKechnie had gone to the mound to console Derringer, and take him out, and bring Beggs in, and watch Beggs throw his warmup pitches, it was getting very dark indeed. Now the fans wanted the umpires to call the game; if the seventeenth inning could not be completed, the score would revert to the sixteenth and the game would end in a 0-0 tie instead of a Brooklyn victory. When the plate umpire motioned for the game to go on, they began setting newspapers on fire and waving them at the umpires.

The Reds began a delaying action on the field, prolonging the game in the hope that it would get so dark that it would have to be called. Beggs fielded a tap back to the mound and threw the ball past first base and another run scored. The catcher struggled with a tapped ball in front of the plate and found he couldn't pick it up until the batter was safe at first. A single through the suddenly immobile infield drove in two more runs to make it 4-0 Brooklyn, still with no one out.

At this point McKechnie decided to change pitchers again. He strolled slowly out to the mound, conferred with Beggs and then waved in another relief pitcher. A flagrant delay could result in the umpires forfeiting the game to the Dodgers, but a pitching change was a legitimate move and McKechnie took advantage of it. The Dodgers chafed as Jim Turner walked slowly in from the bullpen and warmed up. When the game resumed Casey hit into a ground out the Reds could not avoid making and Walker hit an easy pop fly between third and short. No one bothered to catch the pop-up, but under the infield-fly rule it was an automatic out. [Mickey] Owen trotted from second to third after the ball hit the ground, but no one tried to stop him. Turner threw a wild pitch and Owen jogged slowly home with the fifth run.

Turner continued to throw pitches very wide of the plate, but the batter, [Billy] Herman, swung at them anyway and struck out to end the inning. McKechnie, in an admirable display of chutzpah, protested to the umpires that Herman hadn't been trying. He then argued more validly that it was too dark to play any longer; lights being turned on in homes and offices were visible beyond the outfield fence.

The umpires waved McKechnie away and said finish the game. The Dodgers sprinted out to their positions for the last half of the seventeenth, but Casey, with a 5-0 lead, had trouble getting the ball over the plate. He walked one man, gave up a hit to another and walked a third to load the bases with one out. Durocher was going crazy. "Come on, Hugh, God damn it!" he cried. Casey got the second out on a force play as a run scored, and finally threw out [Eddie] Joost for the last out, amid mocking cheers from the fans.

--Robert W. Creamer

Baseball in '41

IMAGE: 1941 Brooklyn Dodgers yearbook

3rd INNING

Ballplayers as Entertainers

[In the early 1900s] outstanding players and members of pennant-winning clubs could make considerable money in show business. Ty Cobb ... once played the lead in College Widow, a play whose theme was changed from football to baseball to accommodate him. Charlie Dooin sang with Dumont's Minstrels in Philadelphia, and Larry Doyle was the villain in a melodrama. Johnny Kling put on a billiard exhibition. Doc White, the songwriter ... formed a quartet with Artie Hofman, Addie Joss and Jimmy Sheckard. In 1912 four teammates formed the Boston Red Sox Quartette.

Rube Marquard made his debut in Hammerstein's in 1911. The following year he did an act with his wife-to-be, actress Blossom Seeley, in which they danced something called the "Marquard glide." Joe Laurie, the famous vaudevillian, who saw Marquard's act, remembered that he sang very well. Another act featuring the two was called "The Suffragette Pitcher." The report on that was not so kind. Sporting News stated that as an actor Marquard was one of the greatest living left-handed pitchers.

Rabbit Maranville took the stage too. A story has it that while he was regaling a theater audience with baseball stories he simulated a steal of second base; he was so realistic that he slid over the footlights, landed on top of the first violinist, and bounced into the snare drum, spraining his leg. Rube Waddell was paired with another zany pitcher, Bugs Raymond, in a play named "Stain of Guilt." Christy Mathewson and Chief Meyers made a big hit in 1910 with May Tully in a sketch called "Curves," written for them by the sportswriter Bozeman Bulger. They were booked for seventeen weeks, and Matty was said to have received nearly $1000 a week. His manager, John McGraw, reportedly was paid $2500 a week on the Keith Circuit in 1912 for a monologue called "Inside Baseball."

Joe Tinker surprised everyone by making quite a hit in vaudeville. The New York Telegraph called his skit "A Great Catch" a "clever little piece" that well deserved the applause it got. Tinker also received favorable notices, one of them in Variety, for other shows in which he appeared .... Evidently impressed with his reviews, Tinker decided to quit baseball for 1913 and stay on the stage, but he changed his mind and became playing manager of the Cincinnati ball club.

Mike Donlin was even better than Tinker in show business. Joe Laurie thought "Stealing Home," in which Donlin appeared with Mabel Hite in 1908, was "a great act," and comments in various newspapers agreed. The New York World said Donlin's dancing "brought down the house" .... The New York Sun reported that he had "a very fine stage presence" .... Mike Donlin was even better than Tinker in show business. Joe Laurie thought "Stealing Home," in which Donlin appeared with Mabel Hite in 1908, was "a great act," and comments in various newspapers agreed. The New York World said Donlin's dancing "brought down the house" .... The New York Sun reported that he had "a very fine stage presence" ....The success of the act enabled Donlin & Hite to boost their price from $1000 a week to $1500 in New York and $2000 in other cities. So many offers flowed in that Donlin, like Tinker, began talking about not signing with his club the next season. "There is more money in being an actor than in being a ball player," he was quoted as saying. Donlin did interrupt his baseball career, refusing the Giants' offer for 1909, and stayed in vaudeville for the next two years, reportedly making five times the money he would have received as a ball player. Although he did not endear himself to New York baseball fans by his refusal to "help his team," he continued to receive praise as a "popular idol," whose picture appeared in Vanity Fair under the heading "'Broadway Mike' Donlin, the Beau Brummel of Baseball." Donlin returned to baseball in 1912, this time with Pittsburgh, but gave it up again for vaudeville the following year, only to come back in 1914 for his last season. Meanwhile his first wife had died and he had married another actress, Rita Ross, and turned to the movies ... although his obituary in the New York Times said he was never the actor he thought he was.

-- Harold Seymour

Baseball: The Golden Age

IMAGE: Mike Donlin

4th INNING

In the News: Instant Replay in Baseball?

The ball shot off Chase Utley's bat, a drive that hooked toward the right-field foul pole at RFK Stadium. Umpire Rob Drake ruled the ball foul, but TV replays showed it glancing off the pole, a home run.

The blown call, on Sept. 26 in the second inning with two runners on and two outs, was excruciating for the Philadelphia Phillies who were trying to win the National League wild card. Utley popped out to third base to end the threat, and the Phillies went on to lose 4-3.

Plays such as this have general managers seriously discussing adopting instant replay for home runs. It's on the agenda for their annual meetings ....

Baseball doesn't need instant replay, even though it probably would be used only to determine whether balls or fair or foul, and maybe in the beginning just for playoffs.

Phillies GM Pat Gillick disagrees. "I'm in favor of it," he says, without hesitation. "I'm a purist, but the way technology has evolved and the way it's being used in the other sports that you want to get the play right makes sense."

But the game has always been built around the human element of umpires, good and bad. As costly as they are, blown calls are part of the game. What TV replays have reinforced is how accurate umpires' calls really are.

I remember how angry baseball people were on May 31, 1999, when highly respected NL umpire Frank Pulli, on his own, decided to use TV replay to determine if a ball hit by the Florida Marlin's Cliff Floyd was a home run or a double. It was originally ruled a double, and, after Pulli checked the TV, the call remained. Those who run baseball came down hard on Pulli.

....San Diego Padres CEO Sandy Alderson, chairman of the Playing Rules Committee, says he's wary "of legislating a solution to isolated incidents. One lost home run in the course of the season doesn't necessarily merit a change in the rules."

Commissioner Bud Selig says he's made his feelings well known on the subject. "We're using QuesTec (to evaluate umpires) on balls and strike calls, and overall I like things the way they are," he says ....

Several years ago GMs seriously considered TV replay, but since then interest has subsided.

"That all played out against the backdrop of the commissioner who has always been strongly against it," says Alderson .... "On the other hand, I realized then we were only one controversy away from reviving that topic ...."

Jimmie Lee Solomon, who succeeded Alderson [as MLB executive vice president for baseball operations], says, "Every other sport is considering it, and at some point fans are going to keep clamoring and clamoring until we at least take a look at it ...."

Should the GMs reach agreement, their recommendation would go to baseball's playing rules committee, then on to ownership and Selig. The players' union would also have to approve the change.

--Hal Bodley

Nov. 10, 2006

USA Today

5th INNING

Vic Power: From Puerto Rico to Yankee Stadium

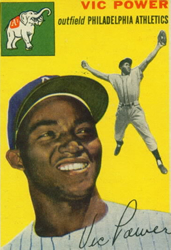

I was born in 1931 in Arecibo, Puerto Rico. My father worked in a factory, but when I was 13 he cut his finger in a work accident and died from tetanus. My mother somehow raised three boys and three girls by sewing dresses. I had a lot of artistic talent, but I decided to become a lawyer so I could get the $10,000 compensation the factory should have paid my mother after my father's death. I played a lot of baseball, but at the time nobody in Puerto Rico thought about playing in the major leagues. In fact, while I had heard of the Yankees and even once wore a Yankee uniform my parents bought in a drugstore, I didn't know who they were or what the major leagues was. I was born in 1931 in Arecibo, Puerto Rico. My father worked in a factory, but when I was 13 he cut his finger in a work accident and died from tetanus. My mother somehow raised three boys and three girls by sewing dresses. I had a lot of artistic talent, but I decided to become a lawyer so I could get the $10,000 compensation the factory should have paid my mother after my father's death. I played a lot of baseball, but at the time nobody in Puerto Rico thought about playing in the major leagues. In fact, while I had heard of the Yankees and even once wore a Yankee uniform my parents bought in a drugstore, I didn't know who they were or what the major leagues was.In 1947, when I was 16, I became the first baseman for Caguas in the winter leagues. I was a good hitter and could catch anything with one hand, so I became a star player in Puerto Rico. In 1948 I received $2,000 for the 4-month season and bought a house in San Juan for my mother and brothers and sisters, who I would support until all the kids graduated high school and were married.

In 1949 I attracted the attention of Quincy Trouppe, who caught and managed in the Negro Leagues. He signed me to play in the summer in Drummondville, Canada, in the independent Provincial League, for $800 a month. It was the first time I had been away from home ... and I didn't speak French or English. But the people were friendly and Quincy treated me like his son .... It was a tough league because they had former major leaguers who weren't yet allowed back in because they had jumped to the Mexican League in 1946. Sal Maglie and Danny Gardella were there. I played right field and hit .329, two points from the batting title. Back in Puerto Rico, I was called Victor Pellot because I used my father's last name, but in Canada I went by my mother's name, Power. That was because when they mispronounced Pellot, with a t rather than a y sound, it sounded like a French sexual term.

In my second year at Drummondville, my salary increased to $1,000 a month and I moved to first base. I had an even better year, leading the league with a .334 average and driving in 105 runs in 105 games. I played in the Provincial League All-Star Game and did well at the plate but made an error. The Yankees had sent their scout Tom Greenwade to watch me. He was the scout who signed Mickey Mantle. He reported that I was a good hitter, average runner, and poor fielder. The Yankees purchased my contract for $7,500. I didn't care about the Yankees, so I threatened not to sign unless the Drummondville general manager gave me a share of that money. He got nervous and handed me a stack of Canadian paper money. I thought it was a lot of money, but it turned out to be only about $500. I found out later that Drummondville didn't own my rights and that I should have gotten the entire $7,500 from the Yankees.

During the winter, the Yankees told me they were going to send me to Kansas City, to play for the Blues .... But three weeks later the Yankees sent me a letter saying I was going to Syracuse in the International League. My contract called for $1,200 a month. I stayed there all of 1951 and batted .294. The Yankees didn't add me to their roster in September, but I went to New York for a physical and was invited to Yankee Stadium to watch them play Boston. Ford Frick, the new Commissioner, was there, too. I sat behind Yogi Berra, the American League's Most Valuable Player, when Allie Reynolds pitched his second no-hitter. In the second game, I saw Joe DiMaggio hit a 3-run homer. I was happy to see him before he retired.

(to be continued...)

--Vic Power

We Played the Game

6th INNING

2006 MVPs

NATIONAL LEAGUE

Ryan Howard (PHI) (20 1st place votes) 388 pts.

Albert Pujols (STL) (12 1st place votes) 347 pts.

Lance Berkman (HOU) 230 pts.

Carlos Beltran (NYM) 211 pts.

Miguel Cabrera (FLA) 170 pts.

Alfonso Soriano (WSN) 106 pts.

Jose Reyes (NYM) 98 pts.

Chase Utley (PHI) 98 pts.

David Wright (NYM) 70 pts.

Trevor Hoffman (SDP) 46 pts.

Others: Andruw Jones (29), Carlos Delgado (23), Nomar Garciaparra (18), Rafael Furcal (11), Garrett Atkins (10), Matt Holliday (10), Aramis Ramirez (5), Freddy Sanchez (5), Chris Carpenter (4), Chipper Jones (3), Mike Cameron (2), Jimmy Rollins (2), Bronson Arroyo (1), Jason Bay (1)

AMERICAN LEAGUE

Justin Morneau (MIN) (15 1st place votes) 320 pts.

Derek Jeter (NYY) (12 1st place votes) 306 pts.

David Ortiz (BOS) 193 pts.

Frank Thomas (OAK) 174 pts.

Jermaine Dye (CWS) 156 pts.

Joe Mauer (MIN) 116 pts.

Johan Santana (MIN) (1 1st place vote) 114 pts.

Travis Hafner (CLE) 64 pts.

Vlad Guerrero (LAA) 46 pts.

Carlos Guillen (DET) 34 pts.

Others: Grady Sizemore (24), Jim Thome (17), Alex Rodriguez (13), Jason Giambi (9), Johnny Damon (7), Justin Verlander (7), Ichiro Suzuki (7), Joe Nathan (6), Manny Ramirez (6), Miguel Tejada (5), Raul Ibanez (4), Robinson Cano (3), Paul Konerko (3), Magglio Ordonez (3), Vernon Wells (3), Carl Crawford (2), Mariano Rivera (2), Kenny Rogers (2), Chien-Ming Wang (2), Troy Glaus (1), Gary Matthews Jr. (1), A. J. Pierzynski (1), Michael Young (1)

Ryan Howard becomes the third player in ML history to win the MVP and the Home Run Derby in the same year. The previous two: Cal Ripken Jr. (1991) and Andre Dawson (1987). Morneau became just the second Canadian player to win the MVP Aaward, the first being Larry Walker in 1997 -- ed.

7th INNING

Year in Review: 1915

It was much like yesterday's victor reentering the arena without his armor or weapons that brought glory the time before.

The Athletics entered this season with the American League championship but without the players that won it. Financial pressures had caused manager Connie Mack to sell most of his high-salaried veteran players for whom the rival Federal League had created a bull market. Ace pitchers Eddie Plank and Chief Bender had signed with the Federal League and Eddie Collins and Eddie Murphy went to the Chicago White Sox during the winter. Jack Coombs was released by Mack and picked up by Brooklyn. In addition to these divestments, Frank Baker decided to pack baseball in and devote full time to his farm. Mack, nevertheless, felt he could defend his championship with the good young talent he had held in reserve behind his veterans. The kids, however, fell on their faces at bat and on the mound, and the A's fell deep into the second division from the very start. On the way to 109 losses, the worst record in the Athletics' 15-year history, Mack continued unloading during the season, sending Bob Shawkey to the Yankees and Jack Barry and Herb Pennock to the Red Sox.

Barry played in his third World Series in as many years as the Boston Red Sox edged the fast-closing Detroit Tigers for first place. The Tigers held the top spot for most of the first half, but a slump enabled the Bosox to take over the lead which they never relinquished. Tris Speaker and Duffy lewis starred with the bat for Boston, and deep pitching gave the Red Sox an edge over the rest of the circuit. Five starters won 14 or more games: righties Rube Foster, Ernie Shore, and Joe Wood, and lefties Dutch Leonard and Babe Ruth. In addition, rookie submarine pitcher Carl Mays provided the best relief work in the league. Ruth won 18 games in his first full season, while unveiling a glimpse of things to come as he led the champions in home runs with four blasts in 92 times at bat. Detroit finished 2-1/2 games out with Ty Cobb, Sam Crawford and Bobby Veach leading the attack. Cobb won his ninth consecutive batting title with a .369 average, while setting a modern stolen base record with 96 thefts. Barry played in his third World Series in as many years as the Boston Red Sox edged the fast-closing Detroit Tigers for first place. The Tigers held the top spot for most of the first half, but a slump enabled the Bosox to take over the lead which they never relinquished. Tris Speaker and Duffy lewis starred with the bat for Boston, and deep pitching gave the Red Sox an edge over the rest of the circuit. Five starters won 14 or more games: righties Rube Foster, Ernie Shore, and Joe Wood, and lefties Dutch Leonard and Babe Ruth. In addition, rookie submarine pitcher Carl Mays provided the best relief work in the league. Ruth won 18 games in his first full season, while unveiling a glimpse of things to come as he led the champions in home runs with four blasts in 92 times at bat. Detroit finished 2-1/2 games out with Ty Cobb, Sam Crawford and Bobby Veach leading the attack. Cobb won his ninth consecutive batting title with a .369 average, while setting a modern stolen base record with 96 thefts.While the Athletics were plummeting into the depths of the American League basement, the cross-town rival Philadelphia Phillies shot from a fifth-place finish the previous year into the National League pennant. Rookie manager Pat Moran led his team to eight wins in a row to start the year, and a first-half challenge from the Cubs faded after June to leave the Phillies alone at the top. The two team stars were 31-game winner Grover "Pete" Alexander and league homer-champ Gavvy Cravath, but a strong supporting cast included 21-game winner Erskine Mayer, first baseman Fred Luderus, and slick-fielding rookie shortstop Dave "Beauty" Bancroft. Boston again made a late-seaon rush, but injuries to Bill James and Johnny Evers limited their rise to second place this time around. New manager Wilbert Robinson led a Brooklyn team without stars into a surprising third place finish. The New York Giants fell with a thud into last place; Larry Doyle and Jeff Tesreau continued to star but Christy Mathewson, Rube Marquard, and Fred Snodgrass -- among others -- had bad years to cut the heart out of the Giants.

The Federal League ended its existence at the end of the season, putting an end to the three-league setup and the two years of financial hardship on practically all teams, thus again allowing baseball to relax. The settlement with the Federal League cost $300,000. It was indeed an expensive page in baseball's history.

--David S. Neft, Richard M. Cohen, Michael L. Neft

The Sports Encyclopedia: Baseball (22nd ed.)

NL: Philadelphia, 90-62 ... Boston, 83-69 ... Brooklyn, 80-72 ... Chicago, 73-80 ... Pittsburgh, 73-81 ... St. Louis, 72-81 ... Cincinnati, 71-83 ... New York, 69-83

AL: Boston, 101-50 ... Detroit, 100-54 ... Chicago, 93-61 ... Washington, 85-68 ... New York, 69-83 ... St. Louis, 63-91 ... Cleveland, 57-95 ... Philadelphia, 43-109

IMAGE: Babe Ruth made himself known in 1915

8th INNING

The 1915 World Series

Boston Red Sox (4) v. Philadelphia Phillies (1)

Baker Bowl (Philadelphia), Braves Field (Boston)

By the time the World Series was over, Boston again claimed the championship. This time, however, it belonged to the Red Sox, who won it in a slightly less impressive way than the Braves. Alexander held Boston to one run in winning the first game of the Series for the Phillies, but the Red Sox pitchers took over to win the next four games by holding Philadelphia to a Series .182 batting average. (Neft, et. al, The Sports Encyclopedia: Baseball)

Game 1: Philadelphia 3, Boston 1 Game 1: Philadelphia 3, Boston 1 Game 2: Boston 2, Philadelphia 1

Game 3: Boston 2, Philadelphia 1

Game 4: Boston 2, Philadelphia 1

Game 5: Boston 5, Philadelphia 4

BOSTON: Jack Barry (2b), Hick Cady (c), Bill Carrigan (c), Rube Foster (p), Del Gainer (1b), Larry Gardner (3b), Olaf Henriksen (ph), Dick Hoblitzel (1b), Harry Hooper (of), Hal Janvrin (ss), Dutch Leonard (p), Duffy Lewis (of), Babe Ruth (ph), Everett Scott (ss), Ernie Shore (p), Tris Speaker (of), Pinch Thomas (c). Mgr: Bill Carrigan

PHILADELPHIA: Grover Alexander (p), Dave Bancroft (ss), Beals Becker (of), Ed Burns (c), Bobby Byrne (ph), George Chalmers (p), Gavvy Cravath (of), Oscar Dugey (pr), Bill Killefer (ph), Fred Luderus (1b), Erskine Mayer (p), Bert Niehoff (2b), Dode Paskert (of), Eppa Rixey (p), Milt Stock (3b), Possum Whitted (of, 1b). Mgr: Pat Moran

The Boston home games were played at Braves Field instead of Fenway Park because the former venue could accommodate bigger crowds. The Boston team became the second to win three world championships, twice as the Red Sox and once as the Americans.

9th INNING

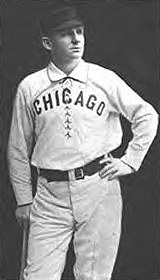

Player Profile: Adrian "Cap" Anson

Nickname: "Pop"

Born: April 11, 1852 (Marshalltown, Iowa)

ML Debut: May 6, 1871

Final Game: October 3, 1897

Bats: Right Throws: Right

6' 207

Hall of Fame: 1939 (Veterans Committee) Hall of Fame: 1939 (Veterans Committee)For most of the 27 years that Cap Anson played baseball he was first baseman for the Chicago White Stockings (Colts). During 20 of those seasons he batted over .200, and collected over 3,000 hits.* When retired he held the records for games played, at bats, hits, doubles, and runs. Charles Comiskey said of him: "He was the greatest batter that ever walked up to hit a baseball .... I played against him, and I know." His best season was 1881 when he led the league in batting (.399), hits (137), total bases (175), RBIs (82), OBP (.442), and OPS (.952). He was the first player to hit three consecutive home runs, five homers in two consecutive games, four doubles in a game, and perform two unassisted double plays in a game. He scored six runs in a game played August 24, 1886.

After a year at Notre Dame, Anson started playing for Rockford in the National Association (NA), then spent four years with the Philadelphia Athletics. During his five years in the NA he batted .350 four times. He was one of the players Chicago White Stockings President William Hulbert negotiated with during the 1875 season, which violated NA rules and, ultimately, led Hulbert to found the National League. Anson was named captain-manager of the White Stockings in 1879 and Chicago went on to win pennants in 1880, 1881, 1882, 1885 and 1886.

In 1888 he signed a 10-year contract to manage the White Stockings/Colts. He was fired after the 1897 season, having failed to win another pennant. In 1898 the Colts called themselves the Orphans to reflect Anson's departure. That year Anson briefly managed the New York Giants (in June and July), then retired. He was made president of the short-lived American Association, became city clerk of Chicago in 1905, and in later years did a stint in vaudeville. He was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1939. Though a century has passed since Anson played, he still holds several Chicago Cubs franchise records, including runs and career hits.

Anson is credited with developing such tactics as the "hit and run" and pitcher rotation. He and Chicago President Al Spalding were innovators in taking players to points south for spring training. Despite being a proponent of segregated baseball and having a combative personality on the field, Anson excelled as an ambassador of the game both at home and abroad, making baseball a more popular sport.

-- Jason Manning

"Cap seemingly swallowed from a fountain of youth, and at times it looked as though he would go on forever." -- Fred Lieb (sportswriter)

* "There is much controversy as to whether he became the first player ever to make 3,000 hits in a major league career; for many years, recognized statistics credited him with precisely that total, but researchers in the 1990s argued that he was incorrectly credited with 20 extra hits in 1879, dropping him to 2,995 according to statistics officially recognized by Major League Baseball. However, if one counts his 423 earlier hits in the NA, the major leagues' predecessor (which Major League Baseball does not) he is well over the mark. He was, by any standard, the first player to make 3,000 hits in his professional career."

-- Wikipedia

"When he retired, [Anson] would take with him statistics providing a strong case for his qualification as not only the greatest player of the last century but of all time. Playing his prime years in a period when the season schedule called for less than 100 games, Anson still managed to accumulate over 3,000 hits and 1,700 RBIs. Projecting his career totals over the 154-game schedule that did not come into existence until after he retired would bring him within easy range of almost every major batting record."

-- David Nemec

The Ulitimate Baseball Book

EXTRA INNINGS

Baseball Dictionary

ball boy

A young man assigned the task of retrieving foul balls. Also, ball girl.

ball club

(1) A baseball team. (2) An organization which supports a baseball team.

ball hawk

(1) A very fast, skilled outfielder, such as Ducky Medwick and Willie Mays. (2) A person who collects balls hit out of the park or into the stands as souvenirs.

ballpark

An enclosed baseball field that includes areas for spectators. A stadium. First used: Baseball Magazine, June, 1908.

The first such enclosed playing area was Union Grounds in Brooklyn, NY, which opened on May 15, 1862. The enclosure was invented and designed by William Cammeyer -- Dickson Baseball Dictionary.

ballplayer

(1) A professional baseball player. (2) Anyone who plays baseball. First used: 1862, correspondence of the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club.

balls and strikes

The count on a batter.

Baltimore chop

A batted ball that hits the ground close to home plate and bounces high in the air, giving the batter time to reach first base. First used: 1910, Baseball Magazine, April.

Despite the fact that the term did not begin to show up in print for several decades, it got its name, by all accounts, in the 1890s when the tactic was perfected by Wee Willie Keeler of the old Baltimore Orioles. Two other Baltimore batsmen (John McGraw and Wilbert Robertson) also used it as a method to get on base. Evidence suggests that at the Orioles' field, the dirt near home plate was purposely hardened to make the ball bounce higher -- Dickson Baseball Dictionary.

banana

(1) A good player. (2) A throw in which the baseball curves too much and misses its mark.

bandbox

A small ballpark where home runs are easy to hit.

e.g., Baker Bowl in Philadelphia in the early 1930s and Ebbets Field in Brooklyn in the 1950s. Today the term is most likely to attach itself to Fenway Park ... in Boston and Wrigley Field in Chicago. Among the newer ballparks, the term has been applied to Oriole Park at Camden Yards, The Ballpark in Arlington, and Coors Field. The term is sometimes used to suggest that a batter's numbers are less impressive because of the dimensions of his home field -- Dickson Baseball Dictionary.

First used: Sporting Life, Feb. 10, 1906.

bang-bang play

An attempted tag when the runner and the ball reach the base simultaneously.

THIS MATERIAL IS REPRODUCED FOR NON-PROFIT EDUCATIONAL AND SCHOLARLY PURPOSES ONLY, WHICH COMPLIES WITH THE DOCTRINE OF FAIR USE AS EXPRESSED IN THE COPYRIGHT ACT OF 19 OCTOBER 1976, EFFECTIVE 1 JANUARY 1978 (TITLE 17 OF THE UNITED STATES CODE, PUBLIC LAW 94-553, 90 STAT. 2541.)

|