9 Innings 9 InningsA Baseball History Reader

J. Manning, Editor

|

Issue # 15: November 21, 2006

DiMaggio Hits in Fifty-Six Straight ... Ebbets Field ... Ebbets Field: Ten Most Memorable Moments ... The Cuban Connection ... Worst Teams: The 1935 Boston Braves ... Stats: Runs ... Year in Review: 1914 ... The 1914 World Series ... Player Profile: Johnny Sain ... They Played the Game

|

Now there's three things you can do in a baseball game: You can win or you can lose or it can rain."

-- Casey Stengel

1st INNING

DiMaggio Hits in Fifty-Six Straight

After the [1941] All-Star game DiMaggio resumed his position at the center of things. He and the Yankees left New York for what was in effect a triumphal tour of the West. The St.Louis Browns advertised his imminent appearance in the newspapers as though he were a circus coming to town. The Chicago White Sox drew 50,000 people to see him play in a Sunday doubleheader, the largest crowd in Comiskey Park in eight years. After the [1941] All-Star game DiMaggio resumed his position at the center of things. He and the Yankees left New York for what was in effect a triumphal tour of the West. The St.Louis Browns advertised his imminent appearance in the newspapers as though he were a circus coming to town. The Chicago White Sox drew 50,000 people to see him play in a Sunday doubleheader, the largest crowd in Comiskey Park in eight years. DiMaggio responded like the superb performer he was. He had seventeen hits in his first thirty-one at-bats after the All-Star game, the glory of his streak rising to a crescendo in its last eight games. He had four hits, including a home run, in his fiftieth straight game, and four hits in eight at-bats before the big crowd in Chicago when he extended the string to fifty-three. He had only one hit, a single, on ... July 14, but the next day he had two and the day after that, in Cleveland, in his fifty-sixth straight game, he had three more.

It was so extraordinary. It was so satisfying. It filled some sort of human need to learn each day that DiMaggio had done it again, that he was still hitting, that his streak was still alive.

Then it ended, and the strange thing about that is that the game in which he was stopped, the one in which he failed, is far more famous than the game before it in which he reached the now almost sacred figure of fifty-six ....

In his first at-bat DiMaggio hit a smashing ground ball down the third-base line, almost directly over the base. [Ken] Keltner was playing deep and near the line and he stabbed at the ball backhanded as it went by. He was in foul territory when he set himself and threw hard to first, just in time to get DiMaggio. Al Smith, the Cleveland starting pitcher, a lefthander, walked DiMaggio the second time he batted, but on his third at bat, in the seventh inning, DiMaggio pulled another hard grounder down the third-base line, and again Keltner made a fine play, grabbing the ball and nipping DiMaggio at first by less than a step.

DiMaggio came to bat for the fourth and last time in the eighth inning, with one out and the bases loaded. Jim Bagby, a right-hander, was the Cleveland pitcher now, and DiMaggio hit another hard grounder, this one to shortstop .... [T]his time it was a double play. That ended the inning and apparently the streak.

People savoring the game remember that the Cleveland fans booed Smith when he walked DiMaggio. They did because while they wanted to see the Indians win they wanted to see DiMaggio hit safely and they were getting neither. In the last half of the ninth the Indians, behind 4-1, rallied to score twice and had the tying run on third base with no one out. Everyone figured if the Indians could get just the runner on third to score, and no more, the game would be tied and would go into extra innings and DiMaggio might get another chance to bat. The Indians could win the game later. But the runner stayed on third while one batter grounded out, and when the second batter hit back to the pitcher the runner got hung up between third and home was tagged out. The next man grounded out, the game was over and so was the streak.

....In baseball DiMaggio is surely a saint, and his downfall, his martyrdom, so to speak, at the hands of Keltner and Smith and Bagby fascinates modern America as much as Joan being burned at the stake fascinated medieval Europe. They both behaved so well.

As Mike Seidel writes, "DiMaggio spoke very carefully after the game." Pete Rose, you will remember, angrily accused the pitcher who stopped him of pitching "like it was the World Series," as though Gene Garber should have laid one in there for Pete to hit. DiMaggio on the other hand was outwardly gracious, although years later he was still simmering at the way Keltner had played his position that night. "Deep?" he said to Seidel. "My God, he was standing in left field." At the time he swallowed his disappointment, spoke carefully to the press and said he was relieved it was over.

But, he added, "I can't say I'm glad it's over. I wanted it to go on as long as it could."

So did we, Joe.

And it has.

....The day after his streak ended [DiMaggio] banged a single and a double off Bobby Feller and was off on another run, a carefree, rampaging hitting binge that carried through sixteen games .... I saw one of those games. DiMaggio hit a homer. I watched him closely each time he got ready for a pitch. He was very still in the batter's box. He stood with his legs wide apart and took almost no stride when he swung. Andy Crichton, in a contrary mood, insisted it was a lousy stance, that it was too restricted, and that DiMaggio would have been an even better hitter if his feet had been a little closer together. Maybe. I don't know. I just remember watching as he stood in the batter's box waiting for a pitch, his hands back, his bat held rather high, though not as high as Jackie Robinson held his bat. DiMaggio never took his eyes off the pitcher. The only thing that wasn't still was the end of his bat, slowly moving like the tip of a cat's tail .... When he swung it was a smooth, graceful thrust of power. I thought it was a beautiful swing. No wasted motion, no fidgeting, no flash.

When the second streak ended early in August, DiMaggio was batting .381 and had hit safely in seventy-two of seventy-three games .... [He] had an affinity for streaks .... In 1933 when he was an eighteen-year-old rookie with the San Francisco Seals he set a Pacific Coast League record by hitting in sixty-one straight. There had been some mention of that when he was nearing fifty-six games ... [a]nd if he had passed sixty-one, someone would have dug up the all-time professional record of sixty-nine, made in 1919 by Joe Wilhoit of Wichita in the Class A Western League.

Possibly the most impressive measure of the validity of DiMaggio's streak is the realization that in all the years that professional baseball has been played in all the leagues from the nethermost minor circuit to the majors, there have been only five batting streaks that lasted fifty games or more, and DiMaggio has two of them. Here are the ten longest streaks of all time (major league performances are in capital letters):

69 -- Joe Wilhoit, Wichita, Western League, 1919 ... 61 -- Joe DiMaggio, San Francisco, Pacific Coast League 1933 ... 56 -- JOE DiMAGGIO, NEW YORK, AMERICAN LEAGUE, 1941 ... 55 -- Roman Mejias, Waco, Big State League, 1954 ... 50 -- Otto Pahlman, Danville, Three-Eye League, 1922 ... 49 -- Jack Ness, Oakland, Pacific Coast League, 1915 ... 49 -- Harry Chozen, Mobile, Southern Association, 1945 ... 46 -- John Bates, Nashville, Southern Association, 1925 ... 44 -- WILLIE KEELER, BALTIMORE, NATIONAL LEAGUE, 1898 ... 44 -- PETE ROSE, CINCINNATI, NATIONAL LEAGUE, 1978.

--Robert W. Creamer

Baseball in '41

NOTE: During DiMaggio's streak he had 91 hits -- 56 singles, 16 doubles, 4 triples, 15 homers -- with 55 runs scored. He walked 21 times and struck out just 7 times in 223 at-bats -- ed.

2nd INNING

Ebbets Field

Of all the ballparks that no longer exist, none have been romanticized more than Ebbets Field. From 1898 to 1912, the Brooklyn Dodgers played at Washington Park, near the Gowanus Canal on Third Street and Fourth Avenue in the Red Hook section of Brooklyn. When Washington Park became cramped, Dodger owner Charlie Ebbets moved a couple miles west to Flatbush, where he built a new ballpark .... Of all the ballparks that no longer exist, none have been romanticized more than Ebbets Field. From 1898 to 1912, the Brooklyn Dodgers played at Washington Park, near the Gowanus Canal on Third Street and Fourth Avenue in the Red Hook section of Brooklyn. When Washington Park became cramped, Dodger owner Charlie Ebbets moved a couple miles west to Flatbush, where he built a new ballpark .... Ebbets Field opened on April 9, 1913, with a seating capacity of 25,000, although cold and windy weather held Inauguration Day attendance to less than half that. The visiting Phillies put a further damper on the party by beating the Dodgers, 1-0, despite some heroics by Brooklyn's twenty-two-year-old center fielder, Casey Stengel.

....Originally, Ebbets Field had a covered double-decked grandstand that curved around home plate and on the first-base side continued all the way down to the foul pole. However, on the third-base side the grandstand went only 30 or 40 feet past the infield; uncovered single-decked bleacher seats extended the rest of the way to the left-field foul pole. The fences were 9 feet high all around the outfield and there were no seats in fair territory behind any of the outfielders.

Dimensions were a robust 419 feet from home plate down the left-field foul line, a distant 477 feet to dead center, and a convenient 301 feet down the right-field line. It was a pitcher's park, except for left-handed batters.

....[T]he ballpark did not assume its final shape until the winter of 1931-32. At that time, the covered double-decked grandstand was extended from third base down to the left-field corner and from there over to center field. All of Ebbets Park was thereby completely roofed and double-decked except for right and right-center fields, and the seating capacity was expanded to the neighborhood of 32,000.

Further tinkering with the fences continued throughout the thirties and early forties, eventually stabilizing at 348 feet to dead center, and 297 feet from home plate down the right-field line. It was only about 360-370 feet to the seats in the power alley in left-center, about 315 feet to the wall in the power alley in right-center. What had started out as a pitcher's park was thus transformed into just the opposite ....

The concrete wall in left field was 10 feet high; in right field, backing up against Bedford Avenue, it was 19 feet tall with a 19-foot-high screen above that .... Strangely, the concrete right-field wall was concave to the playing field -- that is, the bottom half of the wall slanted away from the field and then at midpoint it straightened and became vertical. The wall, therefore, was bent at the middle.

The crooked wall baffled visiting outfielders, who often chased every which way after caroming baseballs. Dodger outfielders did better. Right fielders Dixie Walker in the forties and Carl Furillo in the fifties became wizards at playing the wall; they racked up assists year after year, throwing out unsuspecting base runners at second base (and occasionally even at first base.)

....Three innovations were introduced to the world at Ebbets Field, two of which became historical milestones that changed the game of baseball and, to some extent, the world forever. The innovation that had no effect at all was an experiment with yellow baseballs in a game between the Dodgers and the Cardinals on August 2, 1938. Yellow was supposed to be easier to see than white, but the players weren't impressed and the fans didn't like it, so the idea was dropped.

The first historical milestone was major league baseball's television debut, which took place at Ebbets Field on August 26, 1939. With Dodger radio broadcaster Red Barber at the microphone, NBC telecast the first game of a Saturday afternoon doubleheader, Cincinnati vs. Brooklyn ....

The second historical milestone -- the breaking of the color line that had shamed organized baseball since the 1880s -- will always be identified with Ebbets Field and with Branch Rickey, president and general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers in the forties. For millions of Americans, baseball's most thrilling moment occurred not when Bobby Thomson or Bill Mazeroski hit their magical home runs but at 2 P.M. on Tuesday, April 15, 1947, when Jackie Robinson trotted out to his position as first baseman for the Brooklyn Dodgers. Thus ended apartheid in major league baseball.

After 1940, the Dodgers were clowns no more. During the forty five years they called Ebbets Field home, the Dodgers won nine National League pennants -- in 1916, 1920, 1941, 1947, 1949, 1952, 1953, 1955 and 1956 -- but only one World Series (1955).

....Most of Brooklyn took the Dodgers to their hearts and, as a result, an ethnically diverse, racially mixed community found a shared interest through which everyone could be on an equal footing. When the Dodgers moved to Los Angeles, Brooklyn lost a common bond that had restrained a tendency to split into ethnic and racial enclaves.

.... The Dodgers were profitable in Brooklyn, but moved because profits promised to be even greater in Los Angeles. The commissioner of baseball at the time, Ford C. Frick, did not interfere. For the good of baseball and definitely for the good of Brooklyn, he should have ....

The Brooklyn Dodgers played at Ebbets Field for the last time on September 24, 1957, defeating the Pittsburgh Pirates, 2-0, before only 6,702 spectators. The imminent departure of the team was already well known.

Ebbets Field was razed in 1960. When demolition was about to begin -- on a wintry day in February -- Lucy Monroe sang the National Anthem, as she had at the start of many Dodgers ball games.

The high-rise Ebbets Field Apartments now occupy the site. Nearby is the Jackie Robinson Intermediate School.

-- Lawrence S. Ritter

Lost Ballparks

3rd INNING

Ebbets Field: Ten Most Memorable Moments

1. September 16, 1924: St. Louis first baseman Jim Bottomley hits a grand-slam home run, a two-run homer, a double, and three singles in six times at bat, driving in a record twelve runs, as the Cardinals trounce the Brooklyn Dodgers, 17-3.

2. September 21, 1934: The Cardinals win a double-Dean double-shutout doubleheader over the Dodgers, as Dizzy Dean pitches a three-hitter, followed by brother Paul's no-hitter.

3. June 15, 1938: On the occasion of the first night game at Ebbets Field, Cincinnati's Johnny Vander Meer pitches his second consecutive no-hitter, beating the Dodgers, 6-0.

4. October 5, 1941, fourth game of the World Series: Brooklyn catcher Mickey Owen drops the third strike of what would have been the last out of a Dodger victory over the Yankees; given a second chance, the Yankees win the game (and go on to win the Series).

Tommy Henrich heads for first as what should have been the game-ending pitch eludes Dodger

catcher Mickey Owen (Oct. 5, 1941)

5. April 15, 1947, Opening Day: Jackie Robinson becomes the first black player in the major leagues in the twentienth century when he starts the season as first baseman for the Brooklyn Dodgers.

6. October 3, 1947, fourth game of the World Series: Yankee pitcher Bill Bevens is pitching a no-hitter against the Dodgers with two men out in the ninth inning -- when Dodger pinch-hitter Cookie Lavagetto suddenly doubles in two runs to break up the no-hitter and win the game for Brooklyn.

7. August 31, 1950: Brooklyn first baseman Gil Hodges hits four home runs and a single, driving in nine runs, in a 19-3 Brooklyn victory over the Boston Braves.

8. October 1, 1950, the last day of the season: Philadelphia's Robin Roberts pitches a five-hitter and outfielder Dick Sisler hits a dramatic tenth-inning three-run homer to beat the Dodgers, 4-1, and win the National League pennant for the Phillies, their first since 1915.

9. October 7, 1952, seventh and deciding game of the World Series: In the seventh inning, with the bases loaded, Yankee second baseman Billy Martin makes a last-second knee-high catch of a short infield fly ball hit by Jackie Robinson, saving the game and the Series for the Yankees.

10. July 31, 1954: Milwaukee first baseman Joe Adcock hits four home runs and a double, driving in seven runs, in a 15-7 Milwaukee triumph over the Dodgers.

-- Lawrence S. Ritter

Lost Ballparks

4th INNING

The Cuban Connection

Since World War Two, Latin Americans have firmly established themselves in Organized Baseball and now count among the foremost players of the game. Once they were a novelty, represented in the big leagues by a handful of Cubans. In 1904 sportswriter Revere Rodgers observed that Cuban players were "natural born artists" and accurately predicted that in the near future American managers would be recruiting them. In 1911 Rafael Almeida, a third baseman, and Armando Marsans, an outfielder, joined Cincinnati and stuck in the big leagues for three and eight seasons respectively. Clark Griffith, managing Cincinnati in 1911, pioneered in tapping the Cuban market, recognizing it as a source of inexpensive players. Upon transferring to the Washington club in 1912, he continued to seek Cuban talent and shortly introduced two more islanders to the majors, Jacinto Calvo and Balmadero Acosta.

Several more were soon signed up: Angel Aragon, Sr. with the Yankees, Emilio Palmero and Jose Rodriguez with the Giants, Eusebio Gonzalez with the Boston Red Sox, and Oscar Tuero with the St. Louis Cardinals. Rodriguez stayed with the Giants for three years and then became widely known in semi-pro baseball in the metropolitan New York area. Two front-rank Cuban players also made their debut in those years, Miguel Gonzalez and Adolfo Luque. Gonzalez, an expert catcher but weak hitter, played seventeen seasons in the majors and then stayed on as a coach. Baseball lore credits him with the most succinct scouting report in history. The Cuban, whose English left something to be desired, was asked to judge the prospects of a young rookie. After sizing him up, Gonzalez reported: "Good field, no hit." Luque was a clever pitcher with an unusually good curve ball. He had a twenty-year career with various National League teams and in 1923, his best season, was the number-one pitcher of the league, with a record of 27 games won as against only 8 lost. He also finished with the lowest earned-run average, 1.93.

The ugly face of bigotry grimaced at the Cubans too. Not only did they look "different," they might even be Negro or part-Negro. It may very well be true, as often claimed, that a few Negroes slipped into Organized Baseball by passing as Cubans or American Indians. Aware of this possibility, white racists among the fans were always suspiciously on guard against having a Negro "put over on them." This fear compounded the difficultiesd faced by Indians, Cubans, or any dark-skinned players. Many fans believed that Chief Meyers was really a Negro and let him know by yelling "Nigger!" from the stands. Because of his dark complexion, Edmund "Bing" MIller, St. Louis Brown's outfielder, was always called "Booker T. Miller" by club manager Dan Howley ....

....[Garry] Herrmann had the opportunity to better his own club by adding the Cubans Marsans and Almeida. News of their coming to Cincinnati alarmed local lily-whites over the possibility that baseball's unwritten law against Negroes was being violated .... To cover himself, Herrmann made inquiries about the ancestry of the two players through connections he had in Cuba. Victor Munoz, sports expert for the leading Cuban paper, El Mundo, accepted Herrmann's inquiry on its own terms, guaranteeing that the players had nothing but "pure caucasian blood in their veins."

Cuban fans, proud of their countrymen's success in Las grandes ligas, quickly identified with them and followed their daily achievements through reports wired home by special Cuban correspondents traveling with the Cincinnati team. Although heroes in their native land, once they gained a place on an American team, Cubans, like Jewish players, were liable to brutal taunts from other players .... Cuban fans, proud of their countrymen's success in Las grandes ligas, quickly identified with them and followed their daily achievements through reports wired home by special Cuban correspondents traveling with the Cincinnati team. Although heroes in their native land, once they gained a place on an American team, Cubans, like Jewish players, were liable to brutal taunts from other players .... ....Cubans with obviously Negroid features suffered exclusion under Organized Baseball's color ban. A flagrant example was the tragic case of Jose Mendez, a pitcher so expert that he was honored with the sobriquet "The Black Matty," after the Giants' star pitcher, Christy Mathewson. Mendez, a cigar-maker by trade, came to the attention of stateside baseball people by defeating major-league clubs in spring exhibition games in Cuba. In the opinion of a contemporary baseball writer, he would have been worth $50,000 to any major-league club if he could be "whitewashed." John McGraw wanted Cuba's "Black Diamond" for his Giants, but, on the admission of baseball's trade paper, was "prevented by fellow National League executives from importing the Cuban Negro star." So Mendez had to play out his career on the islands, leaving a record that has never been duplicated in Cuban baseball.

-- Harold Seymour

Baseball: The Golden Age

IMAGE: Jose "Black Diamond" Mendez

5th INNING

Worst Teams: The 1935 Boston Braves

If any baseball club deserved to be labeled "America's team" in 1935, it was the Boston Braves. They represented the single most important issue of the day -- the Depression. The hapless Braves lost unceasingly, capriciously, and dispiritedly -- in perfect harmony with the hopelessness of their times. They wound up with the worst record in the National League in [the 20th] century with a woeful mark of 38-115 .... The Braves tumbled so far behind into last place, 61-1/2 games out, that they needed a telescope to see the seventh-place Phillies 26 games ahead of them.

They lost in close games and in routs. They lost on dropped pop flies and muffed grounders. They even lost to the Arthur Fisher Shoe Co. team of Randolph, Massachusetts, in an exhibition game.

Part of the problem was that the Braves needed three kinds of pitching -- left-handed, right-handed, and relief. Ben Cantwell dropped 13 decisions in a row on his way to an awful mark of 4-25. Hardly intimidating, Cantwell struck out only 34 batters in 210 innings .... The other starters were nearly as crummy: Earl Brandt, 5-19; Bob Smith, 8-18; and the "ace" of the staff, Fred Frankhouse, 11-15.

Another problem for the Braves was the aging Babe Ruth. He joined Boston after the Yankees released him at the end of the 1934 season. Judge Emil Fuchs, owner of the financially-strapped Braves, signed Ruth as a gate attraction. But at age 40 ... Ruth hurt the team more than he helped it. His new teammates resented him because he drew a large salary, flouted training rules, lived apart from the rest of the players when on the road, and showed a definite lack of interest in the team's welfare. All of this could have been tolerated had he produced at the plate. But he hit only 6 homers and batted a paltry .181 in 28 games before quitting baseball for good, two months into the season.

Boston had just one bona fide star, Wally Berger, who walloped 34 homers and drove in 130 RBIs ....

Figuring they were suffering enough out in the real world, fans stayed away from Braves Field. Fewer than 100 rooters were on hand for a July 28 doubleheader in which Boston lost both ends to Brooklyn .... Three days later the Braves game was postponed so that their ball park could be used for the Danno O'Mahoney - Don George wrestling match.

Because the team was close to bankruptcy, the players spent their scheduled off-days playing exhibition games against semi-pros and minor leaguers. It was believed that the Braves were more likely to draw paying crowds the further away from Boston they played.

....They hit a 15-game losing skid in July and, when they finally won, a local headline read, "The Slaughter of the Innocents Is Halted." But the Braves went right back to their winless ways. From August 18 until September 14, the lackluster team won only two of 30 games.

When the embarrassing season finally came to an end, new club management wanted to remove the stigma of utter failure from the team. So the club invited fans to submit a new name for the Braves. Thousands of names, from Sacred Cods to Bankrupts, were submitted. The judges picked the short-lived moniker Bees. Braves or Bees, the team still was a second division loser the following year.

-- Bruce Nash & Allan Zullo

The Baseball Hall of Shame 2

6th INNING

Stats: Runs (leaders by decade)

1893-99: Jesse Burkett, 255 ... Billy Hamilton, 945 ... Ed Delahanty, 931 1893-99: Jesse Burkett, 255 ... Billy Hamilton, 945 ... Ed Delahanty, 931 1900-09: Honus Wagner, 1014 ... Fred Clarke, 885 ... Roy Thomas, 862

1910-19: Ty Cobb, 1050 ... Eddie Collins, 991 ... Tris Speaker, 967

1920-29: Babe Ruth, 1365 ... Rogers Hornsby, 1195 ... Sam Rice, 1001

1930-39: Lou Gehrig, 1257 ... Jimmie Foxx, 1244 ... Charlie Gehringer, 1179

1940-49: Ted Williams, 951 ... Stan Musial, 815 ... Bob Elliott, 803

1950-59: Mickey Mantle, 994 ... Duke Snider, 970 ... Richie Ashburn, 952

1960-69: Hank Aaron, 1091 ... Willie Mays, 1050 ... Frank Robinson, 1013

1970-79: Pete Rose, 1068 ... Bobby Bonds, 1020 ... Joe Morgan, 1005

1980-89: Rickey Henderson, 1122 ... Robin Yount, 957 ... Dwight Evans, 956

1990-99: Barry Bonds, 1091 ... Craig Biggio, 1042 ... Ken Griffey, Jr., 1002

IMAGE: Rickey Henderson

7th INNING

Year in Review: 1914

While the specter of World War I loomed over the Western World, baseball had a war of its own in 1914 as a new alliance bid to become a third major league. The previous autumn, the Federal League, an independent minor circuit, had announced plans to achieve major-league status by raiding NL and AL teams for players. The Chicago Cubs lost Joe Tinker and Three Finger Brown to the Feds and further compounded the damage by swapping Johnny Evers, whom they judged to be washed up, to the Boston Braves for Bill Sweeney.

Trading Evers may have been the worst transaction the Cubs made to this point. It certainly qualified as the Braves' best move since the late 1890s. After lagging deep in the second division for a decade, the Braves stirred a smidgen of interest in 1913 by finishing fifth under George Stallings. The jury was still out as to whether Stallings was a tactical genius or a tangle of superstitious beliefs.

Though the Braves languished in last place as late as July 18, Stallings continued to evoke his lucky talismans. He knew that the Fed raiders had helped to create a unique parity in the NL and that he had the pitching and defense to prevail if he could just pull his team into contention. By July 21, the Braves were in fourth place, and three weeks later they reached second with only the Giants above them.

On September 2, Stallings's men wrested the lead away from the Giants for the first time and six days later took first for keeps. The smart money was still on John McGraw to whip his team to the front again down the homestretch, but instead the Giants slumped and the Braves copped 34 of their last 44 games to win going away.

The AL race once again lacked drama as the A's won routinely for the fourth time in five seasons. Those bettors who had lost big on McGraw's Giants felt sure to recoup when the Braves met the A's in the World Series.

Season Highlights

-- David Nemec & Saul Wisnia

Baseball: More Than 150 Years

8th INNING

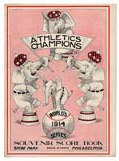

The 1914 World Series

Boston Braves (4) v Philadelphia Athletics (0) Boston Braves (4) v Philadelphia Athletics (0) October 9-13

Fenway Park (Boston), Shibe Park (Philadelphia)

A four-game sweep [by the A's] seemed probable, and many bet for just that to happen. All but a prescient handful bet on the wrong team to sweep. The Braves stunned Chief Bender 7-1 in the Series opener at Philadelphia, won again the following day, 1-0, and then came home so Bostonians could watch in giddy disbelief as their Braves dismantled the A's twice more in succession to cap one of the greatest comback stories in sports annals. (Baseball: More Than 150 Years, Nemec & Wisnia)

Game 1: Boston 7, Philadelphia 1

Game 2: Boston 1, Philadelphia 0

Game 3: Boston 5, Philadelphia 4

Game 4: Boston 3, Philadelphia 1

BOSTON: Ted Cather (of), Joe Connolly (of), Charlie Deal (3b), Josh Devore (ph), Johnny Evers (2b), Larry Gilbert (ph), Hank Gowdy (c), Bill James (p), Les Mann (of), Rabbit Maranville (ss), Herbie Moran (of), Dick Rudolph (p), Butch Schmidt (1b), Lefty Tyler (p), Possum Whitted (of). Mgr: George Stallings

PHILADELPHIA: Frank Baker (3b), Jack Barry (ss), Chief Bender (p), Joe Bush (p), Eddie Collins (2b), Jack Lapp (c), Stuffy McInnis (1b), Eddie Murphy (of), Rube Oldring (of), Herb Pennock (p), Eddie Plank (p), Wally Schang (c), Bob Shawkey (p), Amos Strunk (of), Jimmy Walsh (of), Weldon Wykoff (p). Mgr: Connie Mack

Dick Rudolph was on the hill for 18 of the 39 innings pitched by the Boston Braves -- a record, yet to be broken, for innings pitched in a four-game series.

9th INNING

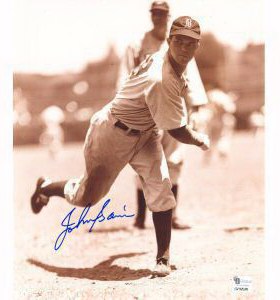

Player Profile: Johnny Sain

Born: September 25, 1917 (Havana, AR) Born: September 25, 1917 (Havana, AR) ML Debut: April 24, 1942

Final Game: July 15, 1955

Bats Right Throws Right

6'2" 200

Johnny Sain, who teamed with Warren Spahn to pitch the Boston Braves to the 1948 National League championship in a pennant race that inspired an enduring baseball rhyme, died Tuesday (November 7, 2006) in Downers Grove, IL. He was 89 .... Sain was a 20-game winner four times, pitched on three World Series championship teams with the Yankees, and was a renowned pitching coach ....

On Sept. 14, [1948] the Boston Post carried a four-line poem by Gerry Hern, the newspapers' sports editor, calling upon Spahn, the Braves' future Hall of Fame left-hander, and Sain, their outstanding right-hander, to bear the pitching burden, resting on off days and -- if luck was with the Braves -- when it rained. The rhyme was shorted by Braves fans to "Spahn and Sain and pray for rain." Spahn and Sain each started three games and each won twice during the next 12 days. There were three off-days and one rainout. Two other pitchers also started games, in between, as the Braves captured the franchise's first pennant in 34 seasons.

John Franklin Sain, a native of Havana, Ark., joined the Braves in 1942, pitching for Manager Casey Stengel. After three years in the Navy, he returned to the Braves and his career flourished at age 28 .... Sain was 20-14 in 1946 and 21-12 in 1947. Then came the season when the Braves emerged from decades of futility to win the pennant by six and a half games over the St. Louis Cardinals. Sain had a 24-15 record and a 2.60 earned run average in 1948 and led the league in victories, complete games (28) and innings pitched (315) .... Sain beat Bob Feller of the Cleveland Indians, 1-0 in the World Series opener. But the Braves lost the Series in six games.

After winning only 10 games in 1949, when he had a sore shoulder, Sain was 20-13 in 1950. But he fell to 5-13 in 1951 and was traded to the Yankees at the end of August for Lew Burdette, who became a pitching star for the Braves. Pitching once more for Stengel, who had moved to the Yankees as manager, Sain bolstered the Yankees as a starter and reliever, winning 11 games in 1952 and 14 in 1953 and then leading the American League in saves, with 22 in 1954.

Sain was traded to the Kansas City Athletics in May 1955, then retired after that season with a record of 139-116 over 11 seasons and a reputation for durability. Except for the final weekend of the 1948 season, when he left a game after five innings to rest for the World Series, he had completed every game he won for the Braves from 1946 to 1948.

Sain had a successful second career as a pitching coach with six teams. He preached keeping batters off balance by changing speeds and using an assortment of deliveries, and lugged around books and tapes advocating the virtues of positive thinking .... As the pitching coach under Manager Ralph Houk when the Yankees won three straight pennants, from 1961 to 1963, Sain taught Whitey Ford how to throw a pitch that alleviated pressure on his elbow and slid sharply. Ford, who had never won 20 games before, won 25 and 24 in two of his three seasons under Sain.

Sain moved to the Twins in 1965, molding Mudcat Grant, Jim Kaat and Jim Perry into a starting staff that brought Minnesota its first pennant. He became the Tigers' pitching coach in 1967, and the next year, Denny McLain, Mickey Lolich and Earl Wilson headed a starting staff that helped bring Detroit a World Series championship.

-- Richard Goldstein

New York Times

EXTRA INNINGS

They Played the Game

Nick Altrock

(1898-1924)

With Al Schacht, Altrock was one of the original Sunshine Boys, baseball's first professional clowns, who performed before games and between doubleheaders for the Washington Senators. As a southpaw pitcher, Altrock won 23 games for the White Sox in 1905 and 20 more in 1906 before his arm gave out.

BORN 9.15. 1876, Cincinnati, OH 83-75, 2.65

Roberto Alomar

(1898-2003)

One of the best second basemen of the 1990s, Puerto Rico-born Alomar was a career .300 hitter who hit 210 home runs and stole 474 bases. He was an All-Star every year from 1990 to 2001 and won ten Gold Gloves as well as four Silver Sluggers. Alomar's wonderful career was somewhat marred by his notorious conflict with umpire John Hirschbeck during a game on 27 September 1996, during which Alomar spit in Hirschbeck's face.

BORN 6.18.66, Salinas, P.R. .273, 111, 571 All-Star 1990, 1991, 1992, 1996, 1997, 1998

Gold Glove 1990 1990 AL ROY 1997 ML-AS MVP

George Brunet

(1956-71)

A pitcher, Brunet spent fifteen years in the majors before moving to the Mexican League, for a total of 33 years in organized baseball. He played for the A's, Braves, Astros, Pilots, Pirates, Cardinals, Senators, Orioles and Angels and ended up with an overall record of 69-93 -- and, for all that, had but one winning season (1970, 9-7).

"Lefty" BORN 6.8.35, Houghton, MI 69-93, 3.62

Jesse Burkett

(1890-1905)

This Hall of Famer led the NL in hits four times, scored 160 runs in 1896, and is the only player aside from Ty Cobb and Rogers Hornsby to hit .400 three times. He set a 19th century record with 240 hits in 133 games in 1897. He was nicknamed "Crab" because he griped constantly.

BORN 12.4.1868, Wheeling, WV .338, 75, 952

Shawn Green

(1993- )

In May 2002 Shawn Green set an MLB record, becoming the first player to have two four-home-run games in a season. Those two games were three weeks apart, with the second being on May 23. Green hit another homer on May 24, tying a big league record of five homers in back-to-back games. In the next game he hit two more, setting a record with seven in three consecutive games.

BORN 11.10.72, Des Plaines, IL .282, 318, 1024 All-Star 1999, 2002 Gold Glove 1999 Silver Slugger 1999

THIS MATERIAL IS REPRODUCED FOR NON-PROFIT EDUCATIONAL AND SCHOLARLY PURPOSES ONLY, WHICH COMPLIES WITH THE DOCTRINE OF FAIR USE AS EXPRESSED IN THE COPYRIGHT ACT OF 19 OCTOBER 1976, EFFECTIVE 1 JANUARY 1978 (TITLE 17 OF THE UNITED STATES CODE, PUBLIC LAW 94-553, 90 STAT. 2541.)

|