9 Innings 9 InningsA Baseball History Reader

J. Manning, Editor

|

Issue # 14: November 14, 2006

The College of Coaches ... Derek Jeter: The Best...or Not? ... Rowdyism ... The Incredible Series ... Johnny Sain: Spahn & Sain ... Stats: World Series Records ... Year in Review: 1913 ... The 1913 World Series ...Player Profile: Vic Raschi ... Baseball Dictionary (backward runner - ball)

|

"Playing this game and surviving this game is tough."

-- Bill Harford, scout

1st INNING

The College of Coaches

PK Wrigley, who didn't understand the game much better in 1961 than he did when he took over [the Chicago Cubs] in 1933, decided to implement a radical change in the leadership structure of the team. He had had it with always having to fire and then hire managers. How to avoid that? Get rid of the post of manager. His scheme was one of the more poorly conceived ideas in the history of the game of baseball: the College of Coaches. PK Wrigley, who didn't understand the game much better in 1961 than he did when he took over [the Chicago Cubs] in 1933, decided to implement a radical change in the leadership structure of the team. He had had it with always having to fire and then hire managers. How to avoid that? Get rid of the post of manager. His scheme was one of the more poorly conceived ideas in the history of the game of baseball: the College of Coaches. ....[Elvin] Tappe suggested hiring a corps of coaches and keeping them as coaches, no matter who was the manager .... But Phil Wrigley wasn't satisfied with Tappe's system. He wanted a system of his own he could implement .... So rather than keep a central corps of coaches no matter who was the manager, as Tappe had suggested, Wrigley made the decisions that (a) the Cubs would be better off not having a manager at all; (b) there would be a pool of coaches from which to pick a head coach; and (c) every few weeks he would switch them around. The players, Wrigley decided, could thus benefit from the accumulated knowledge of the group.

....Said [a] mocking critic of Phil Wrigley's new scheme, "The Cubs have been playing without players for years. Now they're going to try it without a manager."

....One trivia question: Who were the original eight coaches in the College of Coaches? They were Charlie Grimm, Harry Craft, Rip Collins, Bobby Adams, Vedie Himsl, El Tappe, Verlon Walker, and in the minors, Goldie Holt.

Wrigley added to this group of coaches Lou Klein, Freddie Martin, and Charlie Metro, who came from the Detroit Tigers. In 1963, Wrigley hired a new head coach, Bob Kennedy ....

Don Elston recalled ... the fallout from PK Wrigley's oft-discussed ... sociological experiment in team dynamics ....

"....I don't think you will talk to one ballplayer who played under that system that's going to say anything different than it was very hurtful, and it was a very bad situation .... If you look at that list, there is not one decent major league manager in the group. Not one. And yet, you've got them taking turns every five or six weeks. Our concern as players was that not one of them helped one of the others .... All they did was wait until it was their turn .... And this was not a bad team. They had moved Ernie Banks to first, Kenny Hubbs was at second, Andre Rodgers was at short, Ron Santo at third. We had an outfield of George Altman, Lou Brock, and Billy Williams. Dick Bertell caught. This was not a bad team. [Bob] Buhl, [Dick] Ellsworth, [Don] Cardwell, [Cal] Koonce, [Glen] Hobbie, me ....

"Bob Kennedy, who was one of the College of Coaches, took over in '63. That's when they stopped it. When we started '63, we were relieved this thing was over....

"At the trading deadline ... in mid-June of 1964, we made what arguably could have been the worst trade in the history of the Cubs. We traded Lou Brock to the St. Louis Cardinals for pitcher Ernie Broglio. Ernie had won 18 in '63. Lou was a young kid .... Too often in trades the Cubs got these pitchers who were through. Broglio was another one ...."

With the Cubs, Lou Brock had shown flashes of superhuman skills. In '62 as a Cubs rookie he had homered over the center-field bleachers in the Polo Grounds, a distance of 485 feet. Only Joe Adcock of the Milwaukee Braves had ever hit a ball there before him. In '63, Brock stole 24 bases on a team not known for its baserunning. After the trade in June '64, Brock, then only twenty-four, helped lead the Cardinals to the pennant....

....Ron Santo, who began his career in 1960, was a rarity, a young star playing on the Cubs. Phil Cavaretta, who began at age eighteen a quarter of a century earlier, had been the last young star before him. During his fifteen-year career Ron Santo hit 342 home runs. The only career-long third basemen to hit more were Craig Nettles with 390, Eddie Mathews with 512, and Mike Schmidt with 548.

Santo saw firsthand that the Cubs organization of the early 1960s had certain philosophies: It preferred veterans to kids, even if the veterans couldn't play as well; it would trade top prospects for veterans, even if the veterans were at the end of their careers; and it wanted those veterans not to criticize the front office.

Santo recalled how the Cubs traded pitching prospect Ron Perranoski, who later pitched in three World Series with the Dodgers, for over-the-hill utility infielder Don Zimmer. When they couldn't bring themselves to start him at third, the Cubs soon got rid of Zimmer, not for any lack of skill, but because Zim publicly said he felt the College of Coaches, with its lack of stability, was injurious to the Cubs' young players.

....In addition to Ron Santo, the Cubs in the early 1960s had another potential Hall of Fame infielder in Kenny Hubbs, who had signed in 1959. After two years in the minor leagues, Hubbs became the Cubs' regular second baseman in 1962.

As a Little Leaguer, Hubbs had led his Colton, California, team to the finals of the Little League World Series. In one game he hit four home runs. He set a Little League record with 17 straight hits. After the series Kenny and his dad visited Wrigley Field, where he watched Ernie Banks hit two [home] runs.

....With the Cubs in 1962, Kenny Hubbs was a twenty-year-old sensation on an old ninth-place team. He was in the starting lineup on opening day. On June 12 he made an error. He didn't make another one until 78 games later. First he broke the 56-game National League second-base record set by Red Schoendienst, and then he broke the 73-game major league record set by Bobby Doerr. Doerr also held the record of 414 consecutive chances without an error. Hubbs broke that too, handling 418 chances in a row before throwing away a routine grounder on September 5.

At bat, he hit only .260, but he drove in enough runs to make him one of the better second basemen in the game. He was named Rookie of the Year. In 1963, Hubbs helped anchor the infield as the Cubs improved to 82-80 under Bob Kennedy.

Hubbs never made it to spring training the next year. He had conquered his fear of flying by earning a pilot's license. On February 13, 1964, Ken Hubbs and a close friend he was visiting, Dennis Doyle, took off from Provo Airport in Utah to return to Colton, California .... Hubbs lost visibility and must have become disoriented, because the plane was in the air less than a minute when it dived and then crashed onto an ice-covered section of Utah Lake .... Hubbs' death was a blow that delayed the resurgence of the Chicago Cubs for several years ....

The College of Coaches had been an abject failure. The Cubs needed leadership, and they needed it desperately, so much so that Phil Wrigley did something he hadn't done since he took over the Cubs in the 1930s: He hired a strong-willed, autocratic baseball genius, a proven winner capable of leading the team to a pennant. The man's name was Leo Durocher, one of the most famous (and infamous) managers in the history of the game. To get him, Phil Wrigley had to sit back and let Leo make the decisions on trades and other roster moves. But by 1966, Phil Wrigley was embarrassed, and if he had to step back and let Leo take over, so be it.

....Durocher, who managed in the big leagues for twenty-four years, knew how to shape winning teams. His teams won three pennants, in 1941 with the [Brooklyn] Dodgers, and in 1951 and 1954 with the New York Giants. His '54 team had beaten the favored Cleveland Indians in the World Series in four straight.

Before coming to Chicago, Leo's last stint as manager, an eight-year run with the New York Giants, had ended in 1955. During that period he had won twice, finished second twice, third twice, fourth once, and fifth twice. He then moved on to coach the Los Angeles Dodgers under manager Walter Alston. After causing dissension there, he was fired.

....Leo successfully ran the Cubs for six full seasons, and most of a seventh. After a first-year maiden voyage during which the Cubs finished tenth and last, the team under Leo never finished lower than third during the rest of his stay.

His Cubs never won a pennant, but they came damn close, and for almost seven years Cubs fans had the pleasure of being able to root for one of the most exciting teams in Chicago Cubs history.

--Peter Golenbock

Wrigleyville

2nd INNING

Derek Jeter: The Best ... Or Not?

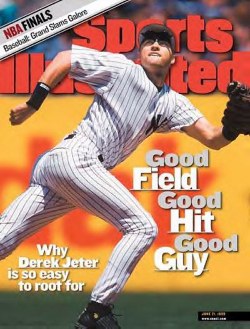

Derek Jeter's fielding poses a dilemma. Depending on whom you debate, Jeter is either one of the best fielding shortstops in the game -- or he is absolutely, positively the worst. The question is whether to believe your eyes when watching him. Derek Jeter's fielding poses a dilemma. Depending on whom you debate, Jeter is either one of the best fielding shortstops in the game -- or he is absolutely, positively the worst. The question is whether to believe your eyes when watching him. Part of the difficulty in judging Jeter is that he is the winningest shortstop in an era of great shortstops .... He has been on four World Series champions in five years .... He must be doing something right.

When baseball people gather to watch Jeter, they smile. They watch him charge balls in the middle of the diamond, range to the outfield and right-field line to gather pop flies, communicate with pitchers and infielders. They love his hustle, his willingness to risk his body to make a play; whether it's diving three rows into the stands or facing down a base runner barreling into second base. They watch the way he captains not only the infield but the outfield, too ....

....Billy Blitzer, a major league scout for almost three decades, says Jeter is one of the best with the glove and arm. Blitzer tracks the Yankees and Mets for the Chicago Cubs organization and has watched Jeter since his days in the minor leagues .... Jeter moves especially well on choppy grounders to the middle of the infield, reaching way down, on the move, for balls with strange topspin and odd bounces on different infield surfaces, scooping the ball, and throwing sidearmed in one motion.

Baseball people will always buzz about a play Jeter made in the American league Divisional Series against the Oakland Athletics. It was a spectacular play that might have ended in disaster, and it crystallizes the debate about whether Jeter is a great or a terrible fielder.

In the third game of the series, the Yankees were facing elimination but leading 1-0. With Jeremy Giambi on first base, the A's Terrence Long hit a shot that Shane Spencer fielded in the right field corner. Spencer threw the ball past both the cutoff man (Alfonso Soriano) and the backup to the cutoff man (Tino Martinez). The ball veered to the first base side of home plate. Jeter surprised everyone in the stadium by fielding the ball. In one motion, Jeter caught the ball and shoveled it to catcher Jorge Posada, who tagged Giambi chugging around to score the tying run. The play protected the Yankees' slender lead and helped them survive a two-game deficit and win the best-of-five series.

The most grizzled veterans, the most cynical reporters, were astonished by the play -- not just Jeter's quick movements or his good sense to shovel the ball to Posada in one motion after catching the ball, but the very fact that he was in position to make the play. Most shortstops would have put themselves closer to second base, ready to take a cutoff throw and holdLong to a double. But Jeter was just a few feet from home plate. After the game, Jeter was asked about the play, and his matter-of-fact reply -- "It was my job to read the play" -- seemed to suggest that the spectacular is standard business for [him].

Here's what the detractors say about Jeter's fielding.

Jeter has limited range. He doesn't always position himself well, so he does not make up for that limited range by being in the right place before the pitch. He has poor instincts, so he takes a split-second too long to react to batted balls. Sometimes he shuffles in the wrong direction as the pitcher throws the ball. He gets a bad jump on the ball. His hands are sometimes unreliable. His throw can be weak and off the mark, which results in more force plays and fewer double plays ....

Jeter does not commit many errors, but that's because teammates compensate for his many weaknesses. Other infielders move toward the shortstop position and cover some of Jeter's ground, leaving gaps in their own positions.

The indictment against Derek Jeter's fielding finds its most forceful expression in statistics.

The most common measure of defensive play is fielding percentage, a simple ratio of errors to chances .... The greatest difference between good and poor fielders is not what they do when they get the ball, but whether they get in position to make the play in the first place .... Fans usually see only the end of the play, not the beginning -- which is most critical ....

In 2001, Jeter finished near the bottom of all statistical measures for fielding among the twenty-one major league shortstops who played in two-thirds of their teams' games. The numbers tell the same story: Jeter does not reach or field balls as well as other shortstops. The leaders in most of the categories included Orlando Cabrera of the St. Louis Cardinals, Alex Gonzalez of the Toronto Blue Jays, and Omar Vizquel of the Cleveland Indians.

....From 1998 to 2003, Jeter finished last among eighteen shortstops who had played at least 500 games, with a Win Shares score of 5.2 over the course of his career (the best of the class, Rey Sanchez, finished with a rate of 9.8). Of 290 shortstops that played at least 3,000 innings through the 2001 season ... Jeter had a better Win Shares rating than only fifty other players -- putting him in the bottom fifth of all shortstops.

-- Charles Euchner

The Last Nine Innings

Win Shares, a formula created by Bill James, tallies assists and expected assists, double plays and expected double plays, error rates, and the player's share of the team's putouts. It also takes into account the number of strikeouts, the ratio of pop flies to ground balls, whether the pitcher is a lefty or a righty, and the dimensions of the ballpark -- ed.

3rd INNING

Rowdyism

....As the [19th] century drew to a close, the National League and many smaller leagues were rife with violent language and behavior -- aimed by players and fans alike at other players, managers, writers, and, particularly, umpires ....Henry Chadwick, nineteenth-century baseball's most revered writer, fan, and philosopher, was obviously horrofied by the slew of unsavory incidents. The following excerpts ... are taken from clippings in Chadwick's unpublished diaries ....

NEW ORLEANS -- At a game of baseball in Carrolton yesterday afternoon the decision of the umpire produced ill feeling, and Gabe Jones, the manager of the Allen Baseball Club, whipped out his revolver and opened fire on the crowd, killing Robert Jones, a spectator, instantly .... James Brook, manager of the opposing club, the Wilson Bas-ball [sic] Club, fired at Jones, but was a bad marksman and hit no one. A general fight ensued and a number of persons were injured, none seriously.

CINCINNATI -- ....In the fourth inning, when a run looked promising for Cincinnati, Vickery threw a ball with extra deliberation and speed, aimed at Harry Vaughn. It hit him on the arm and it is feared the arm is broken. It was palpably intentional.

NEW YORK -- Eddie Burke, the erratic left fielder of the New York Baseball Club, has been in trouble again. He has partially recovered from a severe thrashing at the hands of Second Baseman "Jack" Doyle, also of the New Yorks ....

SYRACUSE, NY -- The baseball season closed here today with a disgraceful scene on the diamond. In the sixth inning, when the score was tied, Harper got caught between the bases and by the dirtiest trick ever witnessed in this city he reached second. Harper deliberately jumped upon Moss, who had the ball ready to touch him, and he spiked the Stars' short stop so hard in the breast that his shirt front was torn almost into ribbons. Moss struck Harper with his first, and a rough-and-tumble fight would have ensued but for police interference.

LOUISVILLE -- Yesterday's game proved an expensive one for the Cleveland club, for warrants were issued this afternoon for the arrest of Cuppy, O'Connor, Tebeau, Childs, McKean, McGarr, Burkett, McAleer, and Blake .... It was shown ... that after the game the treatment of Umpire Weidman on the part of the Cleveland players had been abusive, and of a nature to incite a riot. Several witnesses also testified that Tebeau, McKean and O'Connor had used vile epithets, while McAleer had struck the umpire.

BROOKLYN -- Unless summary action is taken by the league, the national game will speedily degenerate into rough and tumble, eye gouging and head breaking contests, in which the innings will be called rounds and the abilities of the players will be judged by their slugging propensities ....

Yesterday, another row occurred at Pittsburgh .... [T]he game was close and the home team was one run in the lead until Philadelphia went to bat in the last inning. They batted Hastings for three runs and took the lead with two to spare. In Pittsburgh's half the local men filled the bases on a close decision with only one out. Philadelphia kicked hard on the decisions, and while the players were having it out with the umpire, Ely scored from third. This further enraged the visitors. Taylor struck the umpire and Clements was only prevented from doing so by Nash, who ran out on the field from the bench. Taylor and Clements were both fined and removed from the game, Carsey and Grady taking their places. Carsey made a balk, allowing another run and tying the score. Then the visitors all gathered about the umpire again, and the police had to be called ....

-- Joseph Wallace (Editor)

The Baseball Anthology

4th INNING

The Incredible Series

The 1947 World Series was notable for a number of reasons: It was the first in which a black man -- Jackie Robinson, of course -- appeared; it was the first of six in seven years, seven in nine years, won by the New York Yankees; and it was the scene of three of the most unlikely events in World Series history.

Going into the fourth game, the Yankees held a 2-1 lead over the Dodgers. Pitching for the Yankees was an undistinguished right-hander named Floyd Bevens, who had managed but a 7-13 record on a Yankees team that had gone 97-57 over the season. Bevens had little control, but a great deal of luck. Over the first eight innings, he had walked eight men, but allowed only one run -- and had yet to give up a single hit. After three batters in the ninth, holding a 2-1 lead, Bevens was one out from the first no-hitter in Series history. It was an astonishing accomplishment.

Inevitably, perhaps, the wild Bevens would not retain center stage on this day, and the second of the '47 Series' memorable events took place. With two out, and Brooklyn's Carl Furillo on first via a walk, Pete Reiser came up to pinch hit for Dodger pitcher Hugh Casey, while reserve outfielder Al Gionfriddo went in to run for Furillo. Like Bevens, whose nascent no-hitter was totally unexpected, Gionfriddo surprised his opponents and everyone else in the park: he stole second base. It was his third stolen base of the entire year. Yankees Manager Bucky Harris, who had last managed in a World Series in 1925, for the Washington Senators, had Reiser -- the winning run -- walked intentionally; Brooklyn manager Burt Shotton put in Eddie Miksis to run for Reiser, and then had Cookie Lavagetto bat for Eddie Stanky. A fairly decent hitter before World War II, Lavagetto had but 18 hits, only four for extra bases, as a reserve for the Dodgers in 1947. It was perhaps inevitable, on this peculiar day, that the mild Lavagetto would send a deep drive to right field, scoring the unlikely Gionfriddo (and Miksis), and beating the improbable Bevens.

Two days later, back in the Bronx, Gionfriddo returned to register a feat that dwarfed his stolen base and entered Series lore along with Lavagetto's hit and Bevens' thwarted no-hitter. The Yankees led in games, 3-2; the Dodgers led in the sixth inning, 8-5; Joe DiMaggio was at bat, with two men on base. Gionfriddo had come into the game just minutes earlier. Were the game played in virtually any other park but Yankee Stadium, the huge drive DiMaggio hit, 415 feet into the stadium's yawning prairie of a left field, would have been a game-tying home run. As it was, it was intercepted just as it was about to clear the bull-pen fence, caught on the dead run, horribly out of position, his body twisted away from the fence at the last minute, by Al Gionfriddo. Two days later, back in the Bronx, Gionfriddo returned to register a feat that dwarfed his stolen base and entered Series lore along with Lavagetto's hit and Bevens' thwarted no-hitter. The Yankees led in games, 3-2; the Dodgers led in the sixth inning, 8-5; Joe DiMaggio was at bat, with two men on base. Gionfriddo had come into the game just minutes earlier. Were the game played in virtually any other park but Yankee Stadium, the huge drive DiMaggio hit, 415 feet into the stadium's yawning prairie of a left field, would have been a game-tying home run. As it was, it was intercepted just as it was about to clear the bull-pen fence, caught on the dead run, horribly out of position, his body twisted away from the fence at the last minute, by Al Gionfriddo. Though the Dodgers prevailed in that sixth game, the Yankees went on to win the Series the next afternoon, and five more over the next six years. The Dodgers remained their favored opponent, facing off against the Yankees five times in nine years. And Bevens, Lavagetto, Gionfriddo, the unquestioned stars of the '47 Series? Not one of them ever appeared in another big league game.

-- Daniel Okrent & Steve Wulf

Baseball Anecdotes

IMAGE: Al Gionfriddo robs DiMaggio of a three-run homer in Game Six.

5th INNING

Johnny Sain: Spahn & Sain

On April 15, 1947, the [Boston] Braves opened the season in front of 26,623 fans in Brooklyn and I became the first pitcher to face Jackie Robinson .... I was going to pitch Opening Day for the second straight year and I was pretty excited. I didn't care who I pitched against and was concentrating on what I did against all the Dodgers, not on an event that would go down in history. There were no incidents or mischief during the game, which is why nobody would remember who pitched to Robinson .... He went 0-for-3, but reached on an error on a sacrifice bunt and then scored ....

The Dodgers were the best team in the National League in 1947. But the Dodgers had the Giants, and our chief rivals were the St. Louis Cardinals. I didn't like pitching in either of their parks. Ebbets Park was more legitimate before the war. Right field was close, but it was a long ways to center and left until they put box seats out there and made it into a bandbox. There was also a short right field in Sportsman's Park in St. Louis, but what really made it difficult there was the heat and humidity ....

I perspired an awful lot no matter where I pitched. Between innings I'd cool my blood by sticking my hand in an ice bucket with ammonia water. At times I took an ice pack and put it on my stomach. Our uniforms were wool, and if they weren't big enough, they would bind you so you couldn't stretch. That's why we wore baggy uniforms. They weren't that uncomfortable except if we played in 100-degree temperatures in St. Louis ....

I was friendly with all my teammates, especially Warren Spahn, first baseman Earl Torgeson, and utility player Sibby Sisti. But I didn't socialize with them. I was a loner off the field and didn't go out to dinner with this one or that one .... Anyway, the $6-a-day meal money wouldn't buy you much [on the road] .... [O]ur traveling secretary would give us $18 for three days, but instead of going out I'd pocket that money and sign the check in the hotel restaurant and it would be billed to the Braves. And I didn't go drinking with anyone. If we had a game the next afternoon, I probably wouldn't even go to a movie at night. Instead I'd put that dollar in my pocket and go to bed early. So I'd resent it when our clubhouse man, Shorty Young, would wake me up by knocking on doors at the midnight curfew.

I held on to my money. I never had anything growing up in Havana, Arkansas .... My desire was to come out of baseball with as much money as I could. That made it difficult for my wife .... The game itself was an outlet for the players, but the wives didn't have outlets. They had to move from one place to another and worry about schools, finances, and whether their husbands were about to lose their jobs. It was an unstable life ....

We picked up Bill Voiselle from the Giants during the 1946 season, and he became the fourth starter behind me, Spahn, and Red Barrett. He was a tall righthander who threw a wicked fastball. We kidded him that he had three pitches: hard, harder, and harder. He was an aggressive type. Bill was the only pitcher whose uniform number was the name of his hometown: he wore 96 because he came from Ninety Six, North Carolina.

Like me, Warren Spahn pitched briefly for the Braves in 1942, but didn't get much work until he returned from the service in 1946. He was already 25 when he got his first win, a late start for someone who would win 363 games. In 1947 Warren came into his own as a great pitcher, winning 21 games and leading the league in earned run average. It was his first of the thirteen 20-win seasons he'd achieve by 1963 .... I went 21-12, with a 3.53 ERA .... Spahn and I would be the most effective lefty-righty combination in the majors through 1950. Like me, Warren Spahn pitched briefly for the Braves in 1942, but didn't get much work until he returned from the service in 1946. He was already 25 when he got his first win, a late start for someone who would win 363 games. In 1947 Warren came into his own as a great pitcher, winning 21 games and leading the league in earned run average. It was his first of the thirteen 20-win seasons he'd achieve by 1963 .... I went 21-12, with a 3.53 ERA .... Spahn and I would be the most effective lefty-righty combination in the majors through 1950. We were both workhorses but we had different styles. Batters didn't mind hitting against Spahn because he couldn't throw sidearm and his delivery and rhythm were the same on every pitch, straight up and over, every time. But he had uncanny control and painted the corners .... He had all the pitches and then added a screwball .... I was an unorthodox, deceptive pitcher who kept batters off stride by throwing a variation of breaking balls, using different speeds, and using different deliveries and points of release .... The batters that gave me the most trouble were those that could wait, but my motion was so quick it was hard to wait on me. I might give up 8 to 10 hits and keep the other team under 2 runs. I didn't give up many extra-base hits. Spahn might allow fewer hits and yet give up the same number of runs.

I figured that Ewell Blackwell and I were considered the best pitchers in the league at this time. Blackwell was more of a superstar because he was a power pitcher, but we were pretty even when we matched up. I was the only National Leaguer to have won 20 games in both 1946 and 1947. In 1947 he won 22 games and no-hit us in Crosley Field. Bama Rowell was our last hitter and Blackwell struck him out. Rowell came back to the dugout with a big smile on his face and said, "That ball riz!" Blackwell was considered the toughest pitcher on right-handed pitchers because he threw sidearm. I know I didn't wear him out when I faced him at the plate, but I was a very good-hitting pitcher -- in 1947 I batted .346, going 37 for 107 -- and I don't remember him striking me out.

-- Johnny Sain

We Played the Game

6th INNING

Stats: World Series Records

Most World Series Victories:

New York Yankees, 26

Most WS Defeats:

New York Yankees, 13

Most Consecutive WS Appearances:

New York Yankees, 5 (1949-53 and 1960-64)

Most Consecutive WS Defeats:

Detroit Tigers, 3 (1907-09); New York Giants, 3 (1911-13)

Most WS by a Manager:

Casey Stengel, 10 (NYY, 1949-53, 1955-58, 1960)

Most WS Winners Managed:

Joe McCarthy, 7 (NYY, 1932, 1936-39, 1941, 1943); Casey Stengel, 7 (NYY, 1949-53, 1956, 1958)

Most Consecutive Years Managing WS Losers:

Hughie Jennings, 3 (DET, 1907-09); John McGraw, 3 (NYG, 1911-13)

Most Different Series Clubs Managed:

Bill McKechnie, 3 (1925 Pirates, 1928 Cardinals, 1939 & 1940 Reds); Dick Williams, 3 (1967 Red Sox, 1972 & 1973 A's, 1984 Padres)

Most WS Home Runs:

Mickey Mantle, 40 ... Yogi Berra, 39 ... Lou Gehrig 35 Mickey Mantle, 40 ... Yogi Berra, 39 ... Lou Gehrig 35 Most WS Hits:

Yogi Berra, 71 ... Mickey Mantle 59 ... Frankie Frisch 58

Best WS Batting Average (min. 50 at-bats):

Paul Molitor, .418 ... Pepper Martin, .418 ... Lou Brock, .391

Most WS Stolen Bases:

Eddie Collins, 14 ... Lou Brock, 14 ... Frank Chance, Phil Rizzuto, Davey Lopez, 10

Most WS Runs:

Mickey Mantle, 42 ... Yogi Berra, 41 ... Babe Ruth, 37

Most WS Wins:

Whitey Ford, 10 ... Bob Gibson, Allie Reynolds, Red Ruffing, 7

Most WS Strikeouts:

Whitey Ford, 94 ... Bob Gibson, 92 ... Allie Reynolds, 62

Most WS Saves:

Miguel Rivera, 9 ... Rollie Fingers, 6 ... Johnny Murphy, Allie Reynolds, John Wetteland, Robb Nen, 4

Most WS Innings Pitched:

Whitey Ford, 146.0 ... Christy Mathewson, 101.2 ... Red Ruffing, 85.2

7th INNING

Year in Review: 1913

Somehow -- possibly by increased use of the spitball and other trick pitches -- major league pitchers began to regain their mastery over hitters in 1913. Although the cork-centered baseball introduced in 1911 was still around, runs scored dropped by more than 1,000 and the days of the sub-2.00 individual ERA returned. One new stadium, Brooklyn's Ebbets Field, opened.

For the second year in a row, the New York Giants won in excess of 100 games and ended the pennant race before the weather got hot. John McGraw's team featured a typical combination of an overachieving, starless lineup and two or three of the best five pitchers in the league. In this case, they were the 25-11 Christy Mathewson (who won the NL ERA title at 2.06), the 23-10 Rube Marquard, and the 22-13 Jeff Tesreau (who finished third in ERA at 2.17).

Just about the only Giant hitter to show up on the offensive leader board was outfielder George Burns, who hit 37 doubles. Yet Fred Merkle, Chief Meyers, Larry Doyle, and the rest of the New York attack scored 684 runs, third-most in the league.

Gavvy Cravath, the pre-Babe Ruth home run sensation, turned in the year's best offensive season for second-place Philadelphia. He led the league in RBI with 128, homers with 19, and slugging average at .568; his .341 batting average was second-best. The Chalmers Award went to Brooklyn's Jake Daubert, the batting champion at .350.

Pitching also figured in the Phillies' rise to second. Tom Seaton led the NL with 27 wins while notching a 2.60 ERA. Grover Cleveland "Pete" Alexander went 22-8 with a 2.79 ERA.

With great hitting years from Eddie Collins (who led the league in runs with 125), Frank "Home Run" Baker (who batted .337 and drove in 116 runs), and Stuffy McInnis (who hit .324), [the] Philadelphia

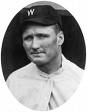

[Athletics] won its third AL pennant in four years. It finished with a 96-57 record, 6-1/2 games ahead of Washington -- or, to be more accurate, Walter Johnson. "The Big Train" had his finest season in 1913, winning 36 and losing only seven and leading the league in wins, ERA, strikeouts, fewest hits per game, and almost everything else. he threw 11 of his career 110 shutouts and pitched a record 55-2/3 consecutive scoreless innings; his 1.14 ERA is the fifth-best single-season performance in history. The Senators played .837 ball with their ace on the mound, .486 without him. Johnson became the first and only pitcher to receive the Chalmers Award. [Athletics] won its third AL pennant in four years. It finished with a 96-57 record, 6-1/2 games ahead of Washington -- or, to be more accurate, Walter Johnson. "The Big Train" had his finest season in 1913, winning 36 and losing only seven and leading the league in wins, ERA, strikeouts, fewest hits per game, and almost everything else. he threw 11 of his career 110 shutouts and pitched a record 55-2/3 consecutive scoreless innings; his 1.14 ERA is the fifth-best single-season performance in history. The Senators played .837 ball with their ace on the mound, .486 without him. Johnson became the first and only pitcher to receive the Chalmers Award. The low-powered Senator offense scored almost 200 fewer runs than did the White Elephants. Washington first baseman Chick Gandil hit .318 and drove home 72 runs, and outfielder Clyde Milan led the AL with 74 stolen bases; they were the [stars] of an attack that finished fifth in the league.

Once again, Ty Cobb and Joe Jackson came in first and second in batting at .390 and .373. Jackson led the league in doubles with 39 and Sam Crawford of the RTigers banged out a league-high 23 triples. None of these feats made much difference for Cleveland or Detroit .... An up-and-coming White Sox staff -- Reb Russell (ERA 1.90), Eddie Cicotte (second in the AL at 1.58), and Jim Scott (also at 1.90) -- compiled the league's top [team] ERA of 2.33.

-- David Nemec, et al.

The Baseball Chronicle

IMAGE: Walter Johnson

8th INNING

The 1913 World Series

Philadelphia Athletics (4) v New York Giants (1)

October 7-11

Shibe Park (Philadelphia), Polo Grounds (New York)

As they had in 1911, Philadelphia defeated the Giants in the World Series. Connie Mack's staff of Chief Bender, Bullet Joe Bush, and Eddie Plank had an easy time of it against a New York lineup depleted by injuries to Merkle, Fred Snodgrass, and Meyers. The Giants' pitching fell apart: Marquard had an ERA of 7.00, Al Demaree had a 4.50 mark, and Tesreau a 6.48. The lone exception was Mathewson, who pitched two complete games, including New York's only victory, and allowed two earned runs in 19 innings. [The Baseball Chronicle, Nemec, et. al.] As they had in 1911, Philadelphia defeated the Giants in the World Series. Connie Mack's staff of Chief Bender, Bullet Joe Bush, and Eddie Plank had an easy time of it against a New York lineup depleted by injuries to Merkle, Fred Snodgrass, and Meyers. The Giants' pitching fell apart: Marquard had an ERA of 7.00, Al Demaree had a 4.50 mark, and Tesreau a 6.48. The lone exception was Mathewson, who pitched two complete games, including New York's only victory, and allowed two earned runs in 19 innings. [The Baseball Chronicle, Nemec, et. al.]Game 1: Philadelphia 6, New York 4

Game 2: New York 3, Philadelphia 0

Game 3: Philadelphia 8, New York 2

Game 4: Philadelphia 6, New York 5

Game 5: Philadelphia 3, New York 1

PHILADELPHIA: Frank Baker (3b), Jack Barry (ss), Chief Bender (p), Joe Bush (p), Eddie Collins (2b), Jack Lapp (c), Stuffy McInnis (1b), Eddie Murphy (of), Rube Oldring (of), Eddie Plank (p), Wally Schang (c), Amos Strunk (of). Mgr: Connie Mack

NEW YORK: George Burns (of), Claude Cooper (pr), Doc Crandall (p), Al Demaree (p), Larry Doyle (2b), Art Fletcher (ss), Eddie Grant (ph), Buck Herzog (3b), Rube Marquand (p), Christy Mathewson (p), Moose McCormick (ph), Larry McLean (c), Fred Merkle (1b), Chief Meyers (c), Red Murray (of), Tillie Shafer (ss), Fred Snodgrass (of), Jeff Tesreau (p), Art Wilson (c), Hooks Wiltse (1b). Mgr: John McGraw

The Philadelphia Athletics became the first team to win three world championships. A rumor that the Athletics were going to throw Game 5 because the franchise had sold tickets for a Game 6 was dispelled when Philadelphia won the fifth game.

9th INNING

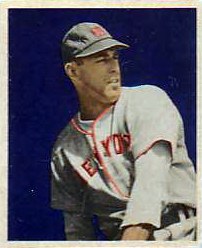

Player Profile: Vic Raschi

Nickname: "Springfield Rifle" Nickname: "Springfield Rifle" Born: March 28, 1919 (West Springfield, MA)

ML Debut: September 23, 1946

Final Game: September 13, 1955

Bats: Right Throws: Right

6' 1" 205

Played for New York Yankees (1946-1953), St. Louis Cardinals (1954-1955), Kansas City Royals (1955)

Postseason: 1947 WS, 1949 WS, 1950 WS, 1951 WS, 1952 WS,. 1953 WS

All Star 1948, 1949, 1950, 1952

Victor John Angelo Raschi out of Springfield, Massachusetts, started late but made up for it, becoming a four-time All-Star during his ten-year career. He was already twenty-eight years old in 1948 when he became a regular part of the Yankee pitching rotation.

Averaging twenty wins a season over the next five years, anchoring a pitching staff that won five straight world championships, the man they called the Springfield Rifle won five World Series games for the Yanks with a 2.24 ERA in 58-2/3 innings. He was truly a big-game pitcher.

A constant five-o-clock shadow, scowling demeanor, blazing fastball, and a work ethic that saw him pitch through pain made him a main man on those great 1950s teams.

In 1949 Raschi won twenty-one games and pitched the pennant-clincher against the Red Sox on the last day of the season. In 1950, Raschi went 21-8 and pitched a two-hit 1-0 shutout in the World Series opener against the Phillies.

In 1951, Raschi again won twenty-one games as well as that year's final World Series game against the New York Giants. In 1952, Raschi's knees were starting to give way on him. But always the tough guy, Raschi toughed it out, winning sixteen games, posting a career-best ERA of 2.78. In the 1952 World Series he won two more games.

Knee problems in 1953 forced Raschi to pitch less than two hundred innings, but he still managed to win thirteen games. In game three of the 1953 World Series against the Dodgers at Ebbets Field, he pitched a complete game but took a 3-2 loss. That was his final appearance as a Yankee.

Contract difficulties ended his time as a Yankee and he was sold to the Cardinals. On the all-time Yankee list, Vic Raschi still ranks fifteenth in strikeouts, thirteenth in innings pitched, eleventh in wins, and ninth in shutouts.

-- Harvey Frommer

A Yankee Century

For Vic Raschi, an earnest, intelligent, no-nonsense individual, another product of a Depression childhood, life had always been serious. When Raschi became a professional athlete, he understood and appreciated the importance of success, and he dedicated himself to that success with a solemn passion. Even at the end of his career he was one of the hardest workers. During spring training he could always be seen running wind sprints and doing sit-ups, working behind gritted teeth long after everyone else had packed it in for the day.

Raschi was a quiet, conservative person, a religious family man who outside of his intimate friends remained closed and introverted. He made a special effort to avoid publicity. When a reporter insisted upon interviewing him, Raschi would be evasive and unresponsive to the questions, and there were times when a particularly annoying reporter would discover his shoes covered with tobacco juice after an interview .... A cold, humorless quality kept jim at arm's length from strangers.

When Raschi crossed the white foul line to the mound, his latent hostility actively simmered. He was grim and ornery, a frightening man to face, and when he pitched even his teammates behind him left him alone. Once, when Raschi was in a jam with runners on base, Stengel wanted Yogi Berra, early in his catching career, to tell Raschi to pitch with more deliberation. While Stengel shouted out to Berra to call time and go out to the mound, Berra kept looking over to the dugout and shaking his head no. Finally, Stengel took some money out of his wallet and shook the bills in the air, a warning that Berra would be fined if he didn't go out there. Reluctantly Yogi called time-out and started to the mound. Getting about halfway, he was met by a brown stream of tobacco juice. "Not another step," barked Raschi, standing imperiously at the top of the mound. "Get the hell out of here now." Berra, without a word, returned to his position behind the plate as Raschi pitched out of the jam.

.... On occasion, when [Raschi] had a big lead, his infielders enjoyed teasing him gently. Raschi had one superstition to which he adamantly adhered. After the Yankees threw the ball around the infield following an out, Raschi insisted that he be positioned with his right foot on the rubber before he would accept the ball from the third-baseman. Most of the time third-basemen Billy Johnson and Bobby Brown respected Raschi's idiosyncrasy, but sometimes they would deliberately throw the ball a couple of feet behind Raschi so he had to reach back, losing his balance and removing his right foot from the rubber to catch it. Raschi would glare menacingly at the offender as the rest of the infielders laughed behind their gloves.

Vic Raschi was one of the best of the modern-day pitchers, for seven years the most dependable pitcher on the Yankee staff, an uncomplaining man who never mentioned the bone chips in his pitching arm and who successfully hid a painful ligament condition in his right knee. "I only have so many years in the game," Raschi once said, "and any time they ask me to pitch, I'm going to pitch."

Between his rookie year in 1947 and his final year as a Yankee in 1953 when Yankee general manager George Weiss coldheartedly traded him after a salary dispute, Victor Angelo John Raschi started 207 games, completed 99 of them, winning 120 and losing only 50: Hall of Fame quality pitching. Raschi was 7-2 for New York his rookie year in 1947, and for the next six years he compiled won-lost records of 19-8, 21-10, 21-8, 21-10, 16-6 and 13-6. With Raschi starring, the Yankees won pennants in '47, '49, '50, '51, '52 and '53, also winning the world series each of those years.

When the Yankees needed to win one game, Raschi was the man usually called on, despite his pitching the last few years with torn cartilages in his right knee. After a game, Raschi's knee would pain him so that he would hide in the trainer's room to kee pthe extent of his injury secret from the press. Even some of his teammates didn't realize how much pain he endured when he was pitching. But Raschi had learned to live with the pain, compensating by taking three strikes and staying off the base paths when a hit by him would have been meaningless.

At the end of each of his superb seasons Raschi exacted a healthy salary from George Weiss, who found Raschi to be as stubborn as he was. Because Raschi was the backbone of the staff and because the Yankees needed him so badly, Raschi usually had the advantage in the negotiations. Every year there would be salary battles .... Raschi merely argued his value to the Yankee team, and what was Weiss going to say, that Raschi wasn't valuable? For years Raschi tied Weiss's hands.

In 1952 Raschi had won sixteen games, but in spring training of 1953 his knee problems were worsening, and Weiss knew it. Despite the knee, after another prolonged salary fight Raschi again got what he was asking with the aid of Casey Stengel's prodding. As Raschi rose to leave Weiss's office after signing his contract, Weiss looked at his big pitcher and said, "Raschi, don't you ever have a bad year."

In '53 Raschi won only thirteen games -- for the big money he was getting, a bad year. When Raschi received his '54 contract calling for a twenty-five percent pay cut, Raschi said to his wife, "Mom, we're gone." Raschi returned the unsigned contract. "Mr. Weiss," he wrote, "I have made a cripple of myself."

That year Raschi was one of a dozen holdouts. After five consecutive world championships, the Yankee payroll was swelling beyong Weiss's penurious budget. When Raschi arrived in St. Petersburg, Florida, to continue negotations he learned that Weiss had sold him to the St. Louis Cardinals, creating a furor among his teammates, but also sufficiently scaring the other holdouts so that they quickly lined up to sign their contracts. A newspaperman informed Raschi of the sale. Weiss hadn't even bothered to tell him. Raschi went to see Weiss and said simply, "Mr. Weiss, you have a very short memory."

1954 was the first year since 1948 the Yankees did not win the pennant. The Raschi sale had made some of the other veterans leery and cynical, hurting the morale of the team. With Raschi, the Yankees could have won in '54. They needed him to win the big one, and he wasn't there.

-- Peter Golenbock

Dynasty: The New York Yankees, 1949-1964

"Vic Raschi had a good fastball and he'd pound the ball on the inside, knocking you down. He was the first pitcher I saw who had a quick slider that would move away from right-handed hitters. And he threw a heavy ball and when you hit it you'd feel it clear up to your shoulder. Raschi was a good pitcher."

-- Eddie Joost

EXTRA INNINGS

Baseball Dictionary

backward runner

A baserunner who, having advanced one or more bases, is forced to return to a previous base. If such a runner has tagged a new base while advancing, he must retouch that base before returning to the original one; e.g., a runner, leaving first base as a ball is hit to the outfield and thinking it will hit the ground, crosses second base and advances beyond third, then realizes that the ball is caught, must return to first, making sure to retag second base on the way. -- Dickson Baseball Dictionary.

bad-ball hitter

A hitter who chases pitches outside the strike zone. In most cases the end result is not a good one for the batter, although some players became "good" bad-ball hitters, i.e. Hank Aaron and Roberto Clemente.

bad bounce

When a batted ball bounces in a direction unanticipated by the fielder. Usually caused by an irregularity in the field. Also, bad hop.

bad call

A ruling by an umpire that is perceived to be incorrect, such as when a strike is called a ball, or when a baserunner reaches base safely but is called out.

bad hands

Said of a player who is a poor fielder.

bag

A square canvas sack filled with sand, sawdust or some other material, which is used to mark first, second and third base. First used: Spirit of the Times, 1857.

bagger

Term used to express the extent of a hit, as in "two bagger" for a double, or "three bagger" for a triple.

bail out

When a batter steps away from a pitch. This usually occurs when an inside pitch appears to be coming straight at the batter.

balk

An illegal act or motion by the pitcher that an umpire decides was intended to deceive a baserunner into making a move. When a balk is called the ball is dead and all runners advance one base. Usually the balk move is called when the pitcher steps on the rubber and appears to be about to deliver to the plate, but doesn't, or when the pitcher fails to come to a stop after the stretch. There are fourteen specific balk situations in the rules. First used: Knickerbocker Rules, 1845.

ball

A pitch judged to be outside the strike zone by the umpire, and which is not swung at by the batter. First used: Knickerbocker Rules, 1845.

THIS MATERIAL IS REPRODUCED FOR NON-PROFIT EDUCATIONAL AND SCHOLARLY PURPOSES ONLY, WHICH COMPLIES WITH THE DOCTRINE OF FAIR USE AS EXPRESSED IN THE COPYRIGHT ACT OF 19 OCTOBER 1976, EFFECTIVE 1 JANUARY 1978 (TITLE 17 OF THE UNITED STATES CODE, PUBLIC LAW 94-553, 90 STAT. 2541.)

|