9 Innings 9 InningsA Baseball History Reader

J. Manning, Editor

|

||

Issue # 10: October 17, 2006

Why Trade the Rock? ... Baseball Goes to the Movies ... The 200-Homer Club ... Hitting for the Money ... The Spitballer ... Stats: Rookies of the Year (NL) ... The Year in Review: 1909 ... The 1909 World Series ... Player Profile: Johnny Callison ... Baseball Dictionary (aspirin-away)

|

||

"People ask me what I do in winter when there's no baseball. I'll tell you what I do. I stare out the window and wait for spring."

-- Rogers Hornsby

1st INNING

Why Trade the Rock?

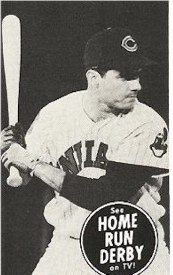

Rocky Colavito ... was everything a ballplayer should be: dark, handsome eyes, and a raw-boned build -- and he hit home runs at a remarkable rate. Best of all, he had a nickname .... Colavito was the Rock ... the Rock of the franchise. "Don't knock the Rock," my father would say. Rocky Colavito ... was everything a ballplayer should be: dark, handsome eyes, and a raw-boned build -- and he hit home runs at a remarkable rate. Best of all, he had a nickname .... Colavito was the Rock ... the Rock of the franchise. "Don't knock the Rock," my father would say. ....The Indians didn't knock the Rock, they just traded him. The date was April 17, 1960. It was the day Cleveland baseball died, or at least went into a deep, dark, seemingly endless coma. Since trading Colavito, the closest the Indians have been to first place at season's end was eleven games out, except in the strike-marred season of 1981. In the last thirty-four years they have finished no higher than third -- and that was just once, in 1968.

No name invokes such utter, raw hatred among Indians fans as [General Manager] Frank Lane. If ever there was The Man Who Destroyed the Indians, Lane was it .... Frank Lane was a wrecking ball ....

The sixth-place finish in 1957 hurt the Indians' owners where they lived -- at the bank. The Tribe drew only 722,256 fans, its worst gate since 1945 .... When Bill Veeck put more than 2.6 million fans in the Stadium in 1948 and 1949, the Indians were the first team to break the 2 million mark in attendance. So 722,256 was a problem. Owner William Daley wanted to do something -- and that something became Lane.

"I'm sure that the Indians knew that Lane would keep the team in the newspapers and in the public eye," said [Hank] Peters. "Fans love trades, and Frank Lane loved to make trades. The bigger the deal, the more controversial, the more he liked it .... He made trades just to make them ...."

It took Lane just three weeks to grab a headline with a monster trade, sending Early Wynn and Al Smith to the White Sox for Minnie Minoso and Fred Hatfield.

....And the deals kept coming.

In his first season, Lane engineered thirty-one trades involving seventy-six players. He also made some that didn't happen. In early June 1958 he tried to trade star pitcher Cal McLish, Mike Garcia, and [Rocky] Colavito to Washington for Eddie Yost, Jim Lemon, and Pedro Ramos ....

Then Lane tried to deal Colavito to Kansas City for a package of Vic Power, Hector Lopez, Woody Held, Dave Melton, Bill Tuttle, and Duke Maas. That was seven for one. The A's decided it was too much.

Meanwhile, Indians fans were wondering, "Why trade the Rock?" In 1958 he hit .303 with 41 homers and 113 RBI. He was only twenty-five ....

"It began when Frank was hired right after the 1957 season," Colavito said. "I had to talk contract with him. I had hit 25 homers and had 84 RBI in 134 games, and all Lane did was tell me how lousy I was. I wanted a $3,000 raise. He offered me $1,500. I told him I wouldn't sign for a rotten raise like that. We went back and forth, and finally he said, 'Take the $1,500 now. I'll give you the other $1,500 if you play well during the season. Don't worry, I'll take care of you.' I didn't know Frank Lane, but I will take a man at his word until I find out that he can't be trusted. In early September 1958, I hit my thirty-fifth home run. I had 102 RBI .... I made an appointment to talk to Lane .... He said he never promised me the other $1,500. I called him a 'no-good liar'"....

"Then Frank tried to sign me for 1959," said Colavito. "He said, 'I'll give you the $1,500 if you take this deal.' It was really a paltry raise. I told him there was no way I'd sign that contract .... We went back and forth all winter, and finally he signed me for double what I had made in 1958. Right then I knew I was in trouble with Frank Lane."

....Colavito's image in the community was impeccable .... Veteran Cleveland Plain Dealer baseball writer Gordon Cobbledick wrote, "He's handsome, boyish, and he doesn't smoke or drink or use violent language."

Or as [Herb] Score said, "Rocky had tremendous charisma. Fans gravitated to him not just because he hit home runs, but Rocky never took a short step on the field .... He was a courageous clutch player ...."

...."What he does is hit so many homers and perform so effectively in the outfield ... and pull so many fans through the turnstiles, and some say he's already won the title as the New Babe Ruth," wrote Cobbledick.

For the third time in three years, Colavito and Lane engaged in their winter contract ritual [in 1960] ....Colavito was still holding out as spring training began. So was another star, a Detroit outfielder by the name of Harvey Kuenn.

Kuenn had led the American League by hitting .353 in 1959 when he made $35,000. He asked for $50,000 [in 1960]. The Tigers laughed .... Then Frank Lane showed up in the Tiger spring training complex at Lakeland, Florida, peddling a Colavito-Kuenn rumor. Kuenn and his wife liked Detroit. At twenty-nine, he had spent eight years with the Tigers. He felt loyal to the team and didn't want to move. The trade rumor scared him. Kuenn signed for $42,000, only a $7,000 raise for winning the batting title.

Then the Tigers GM Bill De Witt and Lane met the writers together, announcing that any trade talks involving Kuenn and Colavito were over.

....Rocky Colavito said that Frank Lane was a "lying S.O.B." Rocky was right. That's because after saying he would not trade Colavito to Detroit for Harvey Kuenn, he did it -- the day before the 1960 season was to open at Cleveland Stadium -- against Detroit.

....A Cleveland headline was: COLAVITO FANS OUT FOR LANE'S SCALP: REACTION VIOLENT AS TRADE STIRS MAN IN STREET. The newspaper held a poll, and the fans voted 9-1 against the deal.

....As Mudcat Grant said, "You want to know why Lane traded Rocky? That's easy. Lane was an idiot."

Comedian Bob Hope, a minor investor in the Indians for years, summed up the mood well: "I'm afraid to go to Cleveland," said Hope. "Frank Lane might trade me."

...."The Indians can win the pennant with Kuenn playing center and the Tigers can finish sixth with Rocky in right field, but the outcome wouldn't satisfy the thousands who want to boil Frank Lane in oil," wrote Gordon Cobbledick.

....While he wouldn't admit it, Colavito seemed staggered by the deal. For any player, the first trade is the worst .... [He] regained his swing in July and finished with 35 homers, 87 RBI and batted .249. Not great by his standards, but it was still more homers and RBI than any member of the 1960 Indians.

As for those Indians, Kuenn played well when he was well, but his body kept breaking down. He had [a] pulled hamstring early in the season, then a wrist injury and a broken foot later in the year. He batted .308 with 9 homers and 54 RBI, but injuries cost him twenty-eight games.

....In November, Lane signed Kuenn to a new contract .... The Cleveland papers were savaging Lane. Ownership was very nervous because attendance dropped from 1.5 million in 1959 to 950,985 in 1960. The Plain Dealer quoted a fan as saying, "With all the trades, I don't even know this club well enough to get sore at it."

....When [Lane] retired, he boasted that he had made more than four hundred trades involving at least one thousand players. But none would be remembered like the Colavito deal.

-- Terry Pluto

The Curse of Rocky Colavito

2nd INNING

Baseball Goes to the Movies

One amusement that competed with professional baseball for the masses' entertainment before World War One was the new motion picture industry. From the the crude nickelodeons it graduated to regular full-length films with "The Great Train Robbery" in 1903. In 1910 the business enjoyed weekly admission of ten million; by 1914 Marie Dressler and Charlie Chaplin were names even more widely known than those of outstanding baseball heroes ....

The movie industry also lent itself to cooperation with baseball. Possibly the first moving pictures of players were taken in 1903 when Napoleon Lajoie and Harry Bay were "immortalized" during a post-season series between Cleveland and Cincinnati. In 1910 a commercial film by Essanay Company entitled "Take Me Out to the Ball Game" was a big hit.

The World Series was a natural for the new media. In St.Louis alone, pictures of the 1908 World Series packed two movie houses twice a day for a week. At first the National Commission regarded filming the World Series as just a novelty and failed to grasp its financial possibilities. But after observing public response, Harry Pulliam admitted that "American enterprise had caught the Commission napping." He declared that players, clubs, and the National Commission should share in the proceeds, since they furnished the attraction. So the Commission soon extracted a fee for World Series movie rights. It sold them for $500 in 1910. Ban Johnson, who disapproved of letting the movies in on the World Series, suggested raising the price to $5000 for the 1911 Series, with a view toward pricing the movie people out of the market. Johnson was not the first baseball man, nor would he be the last, to balk at innovations and to accept change only reluctantly or under pressure. National League President Tom Lynch, however, rejected Johnson's proposal, and $3500 was asked and received for movie rights that year.

But the players were not cut in after all, as Pulliam had envisaged. Representatives of the Giants and Athletics protested to the Commission but were turned down. Players began to complain about posing and "pulling off stunts" for the cameras before games, as ordered by the National Commission, without getting any extra money for it. The issue of player cooperation for publicity purposes arose again on later occasions, with the result that the standard major-league contract now contains a proviso requiring players to lend themselves to a certain amount of public-relations projects.

Baseball began using the movies in another way -- for instructional purposes. Taking movies of players in action so that they can study their faults and correct them is an accepted technique in modern baseball. The idea was conceived back in 1914 by Harry E. Aitken, president of the Mutual Film Corporation and an ardent Giants' fan, who got John McGraw to order movie "machines" for spring training to help the Giants improve their play.

-- Harold Seymour

Baseball: The Golden Age

3rd INNING

The 200-Homer Club

The 200-homer club tells the story of the rise of slugging as the predominant offensive strategy. Prior to the rule changes of 1919 and 1920, teams were constrained by the quality of game baseballs and the preferred style of hitting. The 1913 Philadelphia Phillies, led by Gavvy Cravath and Fred Luderus playing in the friendly confines of the Baker Bowl, set the deadball-era record for home runs at a paltry 73.

The high league batting averages of the 1920s and 1930s allowed serial offenses to flourish and biased player selection toward contact hitters who put the ball in play. By the mid-'20s, most teams would include sluggers but were unlikely to go more than two deep in players who could consistently hit the long ball. So while the Yankees had Ruth and Gehrig and the Athletics had Foxx and Simmons, the remainder of their respective lineups, while including many fine hitters, did not contain a legitimate home run threat.

....The 1938 Yankees were the first team to show significant power depth with five players contributing over 20 home runs -- Lou Gehrig (29), Joe Gibbon (25), Tommy Heinrich (22), Joe DiMaggio (32), and Bill Dickey (27).

Home runs increased steadily through the 1930s and 1940s with a five-year hiatus for World War II, when home runs declined due to loss of talent and to lower-quality baseballs. With the return of the major leaguers from military service, home runs began to increase while, perhaps more important, batting avergaes began to plummet. League batting averages that had stood in the .280s and .290s during the 1920s reached the .260s by the end of the 1940s. With batting averages falling, serial offenses became more and more difficult to sustain and the major leagues began to draft hard-swinging power hitters.

The 1947 New York Giants, led by Johnny Mize, Willard Marshall, Walker Cooper, and Bobby Thomson, were the first team to break the 200-homer barrier, swatting 221 roundtrippers. This total was primarily attributable to the Giants' home park -- the peculiarly-shaped Polo Grounds -- and a cluster of career years among the Giants' key sluggers. During its history, the Polo Grounds increased home runs by approximately 70 percent over a neutral park, and in most seasons the Giants hit substantially more home runs at the Polo Grounds than they did on the road ....

Home runs continued to increase through the 1950s as the mighty Brooklyn Dodgers' team featuring Duke Snider, Roy Campanella, and Gil Hodges exceeded 200 dingers in both 1953 and 1955, while the 1956 Cincinnati Reds led by Frank Robinson, Ted Kluszewski, and Wally Post matched the 1947 Giants' mark of 221 roundtrippers.

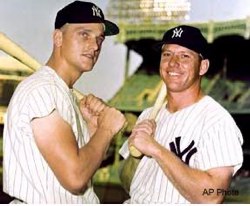

The slugging ethos reached a peak in the American League expansion season of 1961 when the two circuits slammed 2,730 home runs, an increase of 602 home runs (28.3 percent) over the 1960 season. The major league home run per game average reached a record 0.95 in 1961, a number that would not be matched until 1987. This increase in home runs is partially attributable to expansion, but was also assisted by the addition of two strong hitters' parks to the American League, Wrigley Field in Los Angeles and Metropolitan Stadium in Minneapolis. Wrigley Field in Los Angeles, which was the site of 248 home runs during the 1961 season, is particularly notable because of its extremely short power alleys .... The 1961 New York Yankees took advantage of these factors to slam 240 home runs, setting a team single-season home run record. The 1961 Bombers were powered by the greatests 1-2 home run combination in major league history, Roger Maris and Mickey Mantle, who combined for 115 home runs; and by substantial power depth with four other players exceeding 20 home runs, including Moose Skowron (28), Yogi Berra (22), Elston Howard (21), and Johnny Blanchard (21). The slugging ethos reached a peak in the American League expansion season of 1961 when the two circuits slammed 2,730 home runs, an increase of 602 home runs (28.3 percent) over the 1960 season. The major league home run per game average reached a record 0.95 in 1961, a number that would not be matched until 1987. This increase in home runs is partially attributable to expansion, but was also assisted by the addition of two strong hitters' parks to the American League, Wrigley Field in Los Angeles and Metropolitan Stadium in Minneapolis. Wrigley Field in Los Angeles, which was the site of 248 home runs during the 1961 season, is particularly notable because of its extremely short power alleys .... The 1961 New York Yankees took advantage of these factors to slam 240 home runs, setting a team single-season home run record. The 1961 Bombers were powered by the greatests 1-2 home run combination in major league history, Roger Maris and Mickey Mantle, who combined for 115 home runs; and by substantial power depth with four other players exceeding 20 home runs, including Moose Skowron (28), Yogi Berra (22), Elston Howard (21), and Johnny Blanchard (21). With the rule changes of 1962 and 1963, pitchers came to dominate through the 1960s and 1970s, and home runs declined. The primary offensive strategy through this period, especially in the American League, continued to be slugging, and teams playing in strong hitters' parks, such as the Minnesota Twins, the Atlanta Braves, or the Boston Red Sox, reached the 200-homer plateau on occasion. The most notable team to hit 200 roundtrippers during this period was the 1973 Atlanta Braves, the first team to have three players with 40 or more home runs -- including Davey Johnson with 43, Darrell Evans with 41, and Hank Aaron with 40.

The first 200-homer club of the 1980s was the Milwaukee Brewers, who became known as Harvey's Wallbangers after their manager, Harvey Kuenn. The Brewers of the early 1980s were enormously deep, with five genuine home runs threats -- including Gorman Thomas, Ben Ogilvie, Cecil Cooper, Robin Yount, and Ted Simmons, ably supported by line-drive hitter Paul Molitor and supersub Don Money. This depth allowed the Brewers to hit more than 200 home runs on two occasions, 1980 and 1982, when they stroked 203 and 216 respectively....

Home runs per game spiked upward between 1985 and 1987, reaching an unprecedented level of 1.06 in 1987. This accelerated upward movement is attributed to an informal lowering and widening of the strike zone that created a period of adjustment in which the hitters dominated. The 1987 season was the denouement of this home run explosion, with five teams surpassing the 200-homer mark. In 1988, home runs per game plummeted to 1984 levels, and an equilibrium between the pitchers and the hitters was reestablished.

Since the strike season of 1994, home runs have risen to 1987 levels and have remained there ever since with home runs per game exceeding 1.00 in every year. The reasons for this prolonged increase ... [include] expansion in 1993 and 1998, strong trends in stadium architecture favoring home run hitters, improved strength and conditioning of players, the use of smaller and lighter bats to generate increased bat speed, and the adjustment of hitters to become low-ball hitters and drive key pitches with authority. Under these conditions, the 200-homer club has become commonplace, with 33 teams exceeding 200 home runs [per season] since 1994.

With so many teams hitting 200-plus home runs, the all-time single-season team record ... has been in real jeopardy every season since 1994. During 1996, three teams passed the 1961 Yankees, with the Baltimore Orioles setting the pace [with 257]. Baltimore was led by Brady Anderson, who had one of the most extreme career seasons in major league history, slammed 50 home runs .... The Seattle Mariners, who slammed 245 homers, and the Oakland Athletics, with 243 roundtrippers, were close runners-up to Baltimore in the 1996 season, which featured eight clubs with over 200 home runs. The 1996 Baltimore Orioles all-time single-season home run record was short-lived, as the Seattle Mariners, led by Ken Griffey Jr. and Jay Buhner, surpassed it with 264 home runs in 1997.

-- Doug Myers & Bryan Dodd

Batting Around

IMAGE: The M&M Boys, Roger Maris and Mickey Mantle

4th INNING

Hitting for the Money

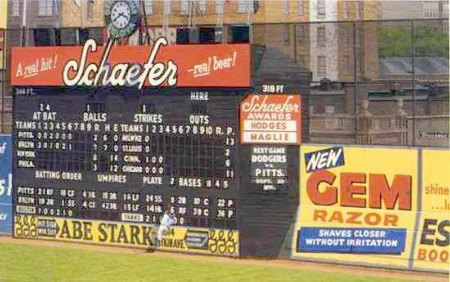

The Abe Stark sign below the Ebbets Field scoreboard reads: "Hit Sign, Win Suit."

On a rainy afternoon in the spring of 1988, the ball game at Fenway Park was rained out. New to the ballpark that season was a billboard on the back wall of the right-field bleachers, approximately 650 feet from home plate, that promised a new pair of shoes to any player who hit a ball off the sign. Forget footwear, the players laughed. Any batter who smacked a ball that far should have been admitted to the Hall of Fame and the Smithsonian simultaneously.

In the Red Sox clubhouse, the topic of conversation turned to hit-this-sign-and-win-something billboards in the days when the prizes were important to strapped ballplayers. The most famous was in right field at Brooklyn's Ebbets Field, where Abe Stark's clothing store promised Hit Sign, Win Suit. That target, however, was situated beneath the scoreboard. Hitting it required a 300-foot line drive six inches off the ground, or a right fielder who fell.

"I remember one in Rochester," Red Sox third-base coach Joe Morgan said. "You had to hit a ball through a hole in the fence to win $10,000 or a new car or whatever it was. Except the hole wasn't lined up with home plate. It faced more toward third base. The wind would have to blow the ball sideways to get through it."

Boston general manager Lou Gorman remembered a huge tire above the outfield fence in Kinston, North Carolina. "If you hit it through the tire, you won $250 from the tire company," said Gorman. "Two guys did it while I was there. Jim Price was one. I think the other was Al Oliver."

Morgan suggested making a telephone call to a guy he knew in his hometown of Walpole, Massachusetts. He was Al Meau, who had pitched for the Class D affiliate of the Boston Braves just after World War II....

The telephone call was placed. "In Blue Field, West Virginia, in 1947, I hit a home run through a truck tire and won $100," said Meau, age sixty-one and working as a security guard. "I was making $135 a month at the time. If you hit the sign on one bounce it was $25. Hit it on the fly, you won $50. Hit it over the sign, you won $75. Hit it through the tire, you won $100. That money helped us pay the bills after our first baby."

-- David Cataneo

Baseball Legends and Lore

5th INNING

The Spitballer

Why are spitballs against the rules? Probably because they're so disgusting. Until 1920, the pitch was legal. Pittsburgh had an otherwise unmemorable pitcher called Marty O'Toole, who ended a five-year career with a 27-36 won-lost record, but who achieved a permanent place in the annals of grossness for his practice of sticking the ball right in his mouth and enthusiastically licking it before he threw. Then there was Burleigh Grimes, the last pitcher to use a legal spitball, who achieved the proper consistency and quantity of saliva by chewing the bark from an elm tree ... and then applying the resultant improved product to the ball in generous gobs. And this guy's in the Hall of Fame!

We do know that if a pitcher puts something slippery on the ball -- Vaseline works well for those concerned about hygiene -- the fingers slide off the ball more easily, and the ball will have less spin. Sometimes a spitball will look like a knuckleball; if it's thrown hard, it will resemble a split-finger fastball, sinking dramatically as it reaches the plate. It's impossible to say convincingly that a spitball gives an inferior pitcher an advantage -- it's hard to throw a good spitball, just as it's hard to throw any other pitch well. Any major league pitcher needs a good fastball; but even when they were legal, not all pitchers threw spitballs or needed to, so it couldn't have been all that easy to do on the one hand, or offered that much of an advantage on the other. When in 1920 they allowed pitchers already using the pitch to continue to use it, only seventeen pitchers registered for the privilege.

Baseballs can be doctored in other, somewhat less revolting ways that will make them do strange things. Scuffing the ball with sandpaper or a nail file will cause it to curve toward the side of the ball that is scuffed. Of course, scuffing adds much smaller protrusions than the stitches, but enough to make the ball move a little more than it otherwise would, and enough to make it a little harder to hit. Scuffing the ball doesn't help everyone -- you have to be a skilled pitcher to take advantage of the technique. And, of course, you have to be willing to cheat. Don Sutton had both qualifications. During a twenty-three-year career, mostly with the Los Angeles Dodgers, he won more than 300 games, and scuffed, cut, and otherwise retooled baseballs so thoroughly and with so many different implements that opposing players used to call him "Black and Decker."

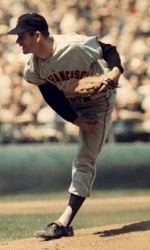

Many more pitchers are accused, or suspected, of throwing illegal pitches than are actually ejected from games for doing so. Gaylord Perry, a 300-game winner who retired in 1983 after a twenty-two year big league career, was one of the unhappy few who were actually thrown out of a game for putting gunk of some kind on the ball. It happened in 1982 when he was pitching for Seattle against Boston. Umpire Dave Phillips watched the bottom drop out of a pitch, and decided that Gaylord couldn't make a baseball do that without some sort of illegal help. He asked to see the ball, and found "some sort of slick substance" on it. He warned Perry that if it happened again, he'd throw him out of the game. Phillips was as good as his word. The next time he saw that sinker, Perry was on his way to the showers. When asked what kind of "slick substance" he found, Phillips said, "I'm an umpire, not a chemist." Perry appealed the decision to Lee MacPhail, who, although he was not a chemist either, nevertheless fined Perry $250 and suspended him for ten days. Many more pitchers are accused, or suspected, of throwing illegal pitches than are actually ejected from games for doing so. Gaylord Perry, a 300-game winner who retired in 1983 after a twenty-two year big league career, was one of the unhappy few who were actually thrown out of a game for putting gunk of some kind on the ball. It happened in 1982 when he was pitching for Seattle against Boston. Umpire Dave Phillips watched the bottom drop out of a pitch, and decided that Gaylord couldn't make a baseball do that without some sort of illegal help. He asked to see the ball, and found "some sort of slick substance" on it. He warned Perry that if it happened again, he'd throw him out of the game. Phillips was as good as his word. The next time he saw that sinker, Perry was on his way to the showers. When asked what kind of "slick substance" he found, Phillips said, "I'm an umpire, not a chemist." Perry appealed the decision to Lee MacPhail, who, although he was not a chemist either, nevertheless fined Perry $250 and suspended him for ten days. Baseball has often winked at spitballer, tolerated them, and laughed about their exploits. It even bestows its highest honor on some of the most notorious: Don Drysdale, Gaylord Perry, and Whitey Ford are all in the Hall of Fame.

-- Nick Bakalar

The Baseball Fan's Companion

IMAGE: Gaylord Perry

6th INNING

Stats: Rookies of the Year (NL)

1947: Jackie Robinson (BRO) ... 1948: Alvin Dark (BSN) ... 1949: Don Newcombe (BRO) ... 1950: Sam Jethroe (BSN) ... 1951: Willie Mays (NYG) ... 1952: Joe Black (BRO) ... 1953: Jim Gilliams (BRO) ... 1954: Wally Moon (STL) ... 1955: Bill Virdon (STL) ... 1956: Frank Robinson (CIN) ... 1957: Jack Sanford (PHI) ... 1958: Orlando Cepeda (SFG) ... 1959: Willie McCovey (SFG) ... 1960: Frank Howard (LAD) ... 1961: Billy Williams (CHC) ... 1962: Ken Hubbs (CHC) ... 1963: Pete Rose (CIN) ... 1964: Dick Allen (PHI) ... 1965: Jim Lefebvre (LAD) ... 1966: Tommy Helms (CIN) ... 1967: Tom Seaver (NYM) ... 1968: Johnny Bench (CIN) ... 1969: Ted Sizemore (LAD) ... 1970: Carl Morton (MON) ... 1971: Earl Williams (ATL) ... 1972: Joe Matlack (NYM) ... 1973: Gary Matthews (SFG) ... 1974: Bake McBride (STL) ... 1975: John Montefusco (SFG) ... 1976: Butch Metzger (SDP) & Pat Zachry (CIN) ... 1977: Andre Dawson (MON) ... 1978: Bob Horner (ATL) ... 1979: Rick Sutcliffe (LAD) ... 1980: Steve Howe (LAD) ... 1981: Fernando Valenzuela (LAD) ... 1982: Steve Sax (LAD) ... 1983: Darryl Strawberry (NYM) ... 1984: Dwight Gooden (NYM) ... 1985: Vince Coleman (STL) ... 1986: Todd Worrell (STL) ... 1987: Benito Santiago (SDP) ... 1988: Chris Sabo (CIN) ... 1989: Jerome Walton (CHC) ... 1990: David Justice (ATL) ... 1991: Jeff Bagwell (HOU) ... 1992: Eric Karros (LAD) ... 1993: Mike Piazza (LAD) ... 1994: Raul Mondesi (LAD) ... 1995: Hideo Nomo (LAD) ... 1996: Tood Hollandsworth (LAD) ... 1997: Scott Rolen (PHI) ... 1998: Kerry Wood (CHC) ... 1999: Scott Williamson (CIN) ... 2000: Rafael Furcal (ATL) ... 2001: Albert Pujols (STL) ... 2002: Jason Jennings (COL) ... 2003: Dontrelle Willis (FLA) ... 2004: Jason Bay (PIT) ... 2005: Ryan Howard (PHI).

BSN=Boston Braves

7th INNING

The Year in Review: 1909

On April 12, 1909, the Philadelphia A's celebrated the opening of Shibe Park, the first all-concrete-and-steel stadium, by beating Boston, 8-1. Some two and one-half months later, the Cubs spoiled the Pirates' debut at Forbes Field, the second modern stadium, by taking a 3-2 squeaker. Yet the Pirates proceeded to end the Cubs' three-year reign as NL champs by winning a club-record 110 games while the A's proved unable to stop the Tigers' Hughie Jennings from becoming the first manager ever to win pennants in each of his initial three seasons as a helmsman.

The Cubs had the consolation of winning 104 games, a record for an also-ran. The A's, however, knew only of despair. They led the AL for most of August, only to succumb to the Bengals' George Mullin and Ed Willett, two of the AL's top three winningest pitchers in 1909.

As the Tigers also had the loop's top two run producers in Ty Cobb and Sam Crawford, their triumph was hardly a shock. The Pirates, in contrast, seemed built around one outstanding player, Honus Wagner, and a collection of aging and uneven pitchers. Some felt the Series could only be won by Pittsburgh if Wagner forgot his 35-year-old legs and played to his zenith.

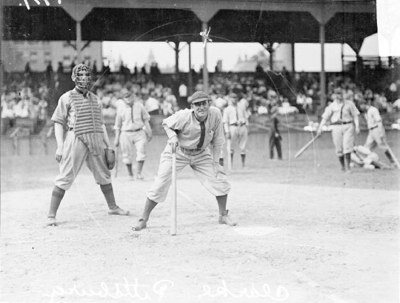

The Pittsburgh Pirates taking batting practice. Fred Clarke is leaning on a bat,

watching one on the fly to right field.

Pirates player-manager Fred Clarke, himself past 36, had a surprise for the Tigers up his sleeve. While the Bengals were looking for 25-game winner Howie Camnitz in the Series opener, Detroit instead drew 27-year-old rookie Babe Adams. When the young hurler from Michigan bested Mullin, it started the Tigers off on the wrong foot for the third postseason affair in a row.

This time, however, Detroit rallied, albeit with little support from Cobb, who hit just .231 in his final Series experience. After six games, the Series was tied at 3-all. For the crucial final contest, Clarke gave the ball for the third time to Adams. This left Jennings to choose either Mullin, working on just one day's rest, or Wild Bill Donovan. The latter had been idle since winning the second contest a full week earlier. Jennings picked Donovan for the start and then switched to Mullin when the Pirates sprang to a 4-0 lead. It did not matter. Adams was invincible, shutting down Detroit 8-0 to become the only rookie ever to win three games in a Series. As for Wagner, he too had a good series, outstripping Cobb in the lone meeting between the dead-ball era's two greatest stars.

-- David Nemec & Saul Wisnia

Baseball: More Than 150 Years

8th INNING

The 1909 World Series

Pittsburgh Pirates (4) v Detroit Tigers (3)

October 8-16 October 8-16 Forbes Field (Pittsburgh), Bennett Park (Detroit)

Game 1: Pittsburgh 4, Detroit 1

Game 2: Detroit 7, Pittsburgh 2

Game 3: Pittsburgh 8, Detroit 6

Game 4: Detroit 5, Pittsburgh 0

Game 5: Pittsburgh 8, Detroit 4

Game 6: Detroit 5, Pittsburgh 4

Game 7: Pittsburgh 8, Detroit 0

PITTSBURGH: Ed Abbaticchio (ph), Bill Abstein (1b), Babe Adams (p), Bobby Byrne (3b), Howie Camnitz (p), Fred Clarke (of), George Gibson (c), Ham Hyatt (of), Tommy Leach (of, 3b), Lefty Leifield (p), Nick Maddox (p), Dots Miller (2b), Paddy O'Connor (ph), Deacon Phillippe (p), Honus Wagner (ss), Vic Willis (p), Chief Wilson (of). Mgr: Fred Clarke

DETROIT: Donie Bush (ss), Ty Cobb (of), Sam Crawford (of, 1b), Jim Delahanty (2b), Bill Donovan (p), Davy Jones (of), Tom Jones (1b), Matty McIntyre (of), George Moriarty (3b), George Mullin (p), Charley O'Leary (3b), Boss Schmidt (c), Oscar Stanage (c), Ed Summers (p), Ed Willett (p), Ralph Works (p). Mgr: Hughie Jennings

Pittsburgh's Babe Adams set a World Series records for most games won in a seven-game series (3), while Detroit's George Mullin set another record for most innings pitched during a seven-game series (32). Adams became the first rookie to start an opening game in a World Series.

9th INNING

Player Profile: Johnny Callison

Born: March 12, 1939 (Qualls, OK) Born: March 12, 1939 (Qualls, OK) Debut: September 9, 1958

Bats Left Throws Right

5'10" 175

Chicago Cubs (1970-71), New York Yankees (1972-73)

A left-handed hitter with a smooth swing, Callison came to the Phillies from the Chicago White Sox in a Dec. 8, 1959 trade for third baseman Gene Freese. He made his debut with the White Sox on Sept. 9, 1958, as a 19-year-old.

Callison played for the Phillies from 1960 through the 1969 season. He was traded by the Phillies to the Chicago Cubs, November 17, 1969, for reliever Dick Selma and outfielder Oscar Gamble. After two years with the Cubs, Callison ended a 16-year major league career playing the 1972-73 seasons with the New York Yankees. In 1,886 career games, Callison batted .264 with 321 doubles, 89 triples, 226 homers and 840 RBI. He scored 926 runs.

While with the Phillies, he was the regular right fielder for eight years. He ranks fourth on the Phillies' all-time list for games played in the outfield, 1,379. Defensively, he led the National League in assists four consecutive years starting in 1962. His high was 26 assists in 1963.

Callison led the NL in triples twice, (10, 1962 and 16, 1965) and doubles once (40, 1966).

He played every game during the 1964 season, the one in which the Phillies saw the pennant disappear during a 10-game losing streak with 12 games left on the schedule and a six and one-half game lead. During loss number seven, Callison, playing even though he had a severe case of the flu, homered three times and drove in four runs during a 14-8 loss to Milwaukee at Connie Mack Stadium on September 27.

Callison was third in the NL in homers (31) and fifth in RBI (104) that year while hitting .274 and scoring 101 runs. He led the league by driving in the winning run 12 times, five by homers. He finished second to St. Louis Cardinals' third baseman Kenny Boyer in the NL Most Valuable Player race. Had the Phillies won the pennant, he probably would have been the league's MVP.

He was the first and only Phillies player to win the MVP Award in an All-Star Game following his dramatic, three-run homer with two out in the bottom of the ninth that gave the NL Stars a 7-4 win at Shea Stadium in 1964.

The following season, Callison hit a career-high 32 homers, scored 101 runs and drove in 93 while leading the league in triples (16). He also had his second three-home run game in 1965.

Among the Phillies' career batting top 10 categories, Callison ranks fifth in triples (84); seventh in extra base hits (534); ninth in homers (185) and total bases (2,426) and tenth in at-bats (5,306) and doubles (265).

"There's nothing he can't do well on a ball field." -- Gene Mauch

-- Official Press Release (Oct. 13, 2006)

Philadelphia Phillies

Callison died October 12, 2006 at the age of 67 -- ed.

EXTRA INNINGS

Baseball Dictionary

aspirin

A pitch thrown so fast that the ball appears to be smaller than it really is.

assist

A throw from one fielder to another that puts out a batter or baserunner.

Association of Professional Baseball Players of America

Non-profit organization that lends a helping hand to ill, handicapped or impoverished former players.

at-bat

Any time the batter gets a hit, makes an out, or reaches base on an error or fielder's choice. A batter makes a plate appearance but is not credited with an at-bat if he is walked, hit by a pitch, completes a sacrifice, or reaches base on a catcher's interference. First used: New York Sunday Mercury, August 10, 1861.

attack point

A point given for every total base and steal by a team in the Japanese Central League. The final tally is used to determine the victor if the game ends in a tie.

attempt

The act of trying to steal a base.

authority

To swing the bat/hit the ball with power and purpose.

automatic out

A batter who rarely hits or walks. Some pitchers are considered automatic outs.

average

A class of baseball statistics that includes batting average, earned run average and slugging average.

away

(1) Used to describe a game played in another team's ballpark (as opposed to a "home" game). A visiting team is, therefore, the "away" team. (2) A pitch thrown out of the strike zone on the side of the plate opposite where the batter stands.

THIS MATERIAL IS REPRODUCED FOR NON-PROFIT EDUCATIONAL AND SCHOLARLY PURPOSES ONLY, WHICH COMPLIES WITH THE DOCTRINE OF FAIR USE AS EXPRESSED IN THE COPYRIGHT ACT OF 19 OCTOBER 1976, EFFECTIVE 1 JANUARY 1978 (TITLE 17 OF THE UNITED STATES CODE, PUBLIC LAW 94-553, 90 STAT. 2541.)

|