9 Innings 9 InningsA Baseball History Reader

J. Manning, Editor

|

Issue # 9: October 10, 2006

|

"Baseball is the only field of endeavor where a man can succeed three times out of ten and be considered a good performer."

-- Ted Williams

1st INNING

Larry MacPhail, Branch Rickey, and the Beginning of the Farm System

After [World War II, Larry] MacPhail moved to Columbus [OH] and ran a glass-making business before getting into automobiles and real estate .... He was an operator, a wheeler-dealer, a man who leaped at opportunities .... [T]he stock market crash occurred in October [1929], and in 1930 MacPhail found himself starting over again.

The stock market crash also affected the fortunes of the Columbus Senators. Most minor league teams were independently owned then, and minor league baseball was much more important than it is now .... The American Association, for example, was a remarkably stable organization. With the International League and the Pacific Coast League it was one of the three Class AA, or highest level, minor leagues in the country (the term "Triple A" was not introduced until 1946). For more than fifty years it had eight teams in the same eight cities -- Minneapolis, St. Paul, Milwaukee, Kansas City, Indianapolis, Louisville, Columbus and Toledo ....

But in 1930 Columbus was a weak franchise. It hadn't won an American Association pennant since 1907, while every other team in the league had won at least once since then, and most of them two or more times. Worse, Columbus had finished in the second division for fifteen straight years ... when MacPhail took charge. The first thing he did was look for help from a major league club. Only a few big league clubs owned minor league teams. Most simply bought players directly from independent minor league operators, or drafted players from the minors at a set fee. Players owned by the big league clubs were "loaned" to minor league teams for seasoning until they were deemed ready for the bigs. Some big league clubs had arrangements with minor league teams in which they provided most or all of the players and paid most or all of their salaries; in exchange, they had a storage bank of reserve players. This was called a working agreement.

MacPhail wanted such an agreement for 1931, his first season, but he had no luck interesting a big league team in Columbus until he met Branch Rickey, who was running the St. Louis Cardinals for owner Sam Breadon. Rickey went a step further; he said the Cardinals would like to buy the club outright. This pleased the Columbus investors, and it pleased MacPhail, who received a two-year contract to continue as president of the club, which was renamed the Columbus Red Birds.

The arrangement worked beautifully, for a while. Rickey supplied Columbus with good ballplayers and MacPhail supplied the promotional spark .... The Cardinals decided to replace the rickety old Columbus ballpark with a brand-new stadium .... [A]t MacPhail's urging lights for night games were installed. Night baseball had been played experimentally here and there for half a century, but the first night game in Organized Baseball did not take place until 1930, at Des Moines in the Western League. In 1931 ... Indianapolis introduced night ball to the American Association. Now in 1932 under [MacPhail's] direction it began in Columbus and attracted big crowds. It was a great year for MacPhail. The Red Birds finished second and drew 310,000 people, which in that dark Depression year was better than six big league clubs did, including Rickey's Cardinals, who drew only 279,000 in St. Louis.

....Before Rickey, when the standard procedure was for major league clubs to replenish their rosters by buying players from the minors, teams like the Cardinals were handicapped because richer clubs like the Chicago Cubs and John McGraw's New York Giants could outbid them. To circumvent this, Rickey assembled a network of minor league teams that were owned or controlled by the Cardinals. On these "farms" they could grow, so to speak, their own players. That's the way it's done today, but it was a novel idea when Rickey introduced it .... He was constantly adding teams. By 1940 the Cardinals owned or controlled thirty-three minor league teams, and the flow of fine ballplayers from the minors to the Cardinals was astonishing. The Yankees began their own farm system after Rickey paved the way, and they, too, kept bringing up outstanding rookies. ....Before Rickey, when the standard procedure was for major league clubs to replenish their rosters by buying players from the minors, teams like the Cardinals were handicapped because richer clubs like the Chicago Cubs and John McGraw's New York Giants could outbid them. To circumvent this, Rickey assembled a network of minor league teams that were owned or controlled by the Cardinals. On these "farms" they could grow, so to speak, their own players. That's the way it's done today, but it was a novel idea when Rickey introduced it .... He was constantly adding teams. By 1940 the Cardinals owned or controlled thirty-three minor league teams, and the flow of fine ballplayers from the minors to the Cardinals was astonishing. The Yankees began their own farm system after Rickey paved the way, and they, too, kept bringing up outstanding rookies. The farm system infuriated Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, the baseball commissioner, who was of the old guard that wanted minor league clubs to remain pretty much free of big league control. Landis particularly objected to the practice of keeping promising players "hidden" by switching them back and forth from roster to roster and up and down from one minor league classification to another to avoid exposing them to the annual baseball draft. The draft had been designed to prevent independent minor league clubs from keeping good players on their rosters year after year instead of letting them rise to the majors. After the majors took control of minor league clubs it was supposed to prevent them from stockpiling quality players on their farms for use at some future time when the parent club needed them.

Landis hated the farm system. Rickey's counterargument was that the minor leagues could not survive without farm-system subsidization by the majors. In the long term he was proved right, but in the 1930s Landis watched Rickey and other operators like a hawk and he swooped down and "freed" minor leaguers -- made them free agents -- whenever he decided there had been a "cover-up." The Yankees acquired the admirable Tommy Henrich as a free agent in 1937 after Landis freed Tommy from the Cleveland Indians' system.

-- Robert W. Creamer

Baseball in '41

IMAGE: Larry MacPhail and Branch Rickey

2nd INNING

Modern Milestones (Part II)

Charles O. Finley's Kansas City Athetics brought some changes to baseball style in the 1960s. First came the green-and-gold uniforms of 1963, ending the exclusivity of white at home, gray on the road. In 1965, the manager (Mel McGaha) and his coaches wore white caps to distinguish them from the players. In 1967 came white shoes for the entire team. And to proper[ly] color coordinate it all, of course, came green shin guards and chest protectors for the A's catchers. Charles O. Finley's Kansas City Athetics brought some changes to baseball style in the 1960s. First came the green-and-gold uniforms of 1963, ending the exclusivity of white at home, gray on the road. In 1965, the manager (Mel McGaha) and his coaches wore white caps to distinguish them from the players. In 1967 came white shoes for the entire team. And to proper[ly] color coordinate it all, of course, came green shin guards and chest protectors for the A's catchers.Tight uniforms originated in 1960, when Willie Mays of the Giants had a tailor go to work on his .... The orlon-wool blend uniforms, better known as "flannels," became history in 1973 when the Yankees and Giants, the last holdouts, moved to knit material. The first to don the new look was the Pittsburgh Pirates, on the day they moved into Three Rivers Stadium -- July 16, 1970. And it was the Pirates -- in 1976 -- who introduced and retained the old-fashioned square baseball caps.

Names on the uniform backs date back to 1960, when the White Sox introduced them, with the Z in Kluszewski backwards to guarantee photo coverage .... Fans have always had a high interest in uniform numbers, so the wearing of 00 by Paul Dade of Cleveland in 1977 should get a place in history, as well as the 0 by Al Oliver of Texas the following year. And while Carlton Fisk's 72 is one of the highest numbers worn in many years, it's not a record. Bill Voiselle wore 96 during his National League pitching career of 1942-50.

....Johnny Bench altered the catcher's chest protector by having one made that fastened at the neck and waist rather than forming a strap down the back. Steve Yaeger of Los Angeles introduced the flap on the mask to protect the neck after he'd been hit by a flying bat. The year of his gift to baseball equipment was 1977.

...."Hawk" Harrelson brought a lot of cosmetic changes to baseball. He popularized the use of a batting glove in 1964 following a day of golf and resulting raw hands. (The glove was first introduced by golf pro Danny Lawler in 1949, when he gave one to Bobby Thomson, but it was in vogue only for batting practice and spring training before Harrelson.)

The Hawk also popularized wrist bands, lamp black under the eyes, and high stirrups, although San Francisco's Tito Fuentes was pulling the sock high around the same time.

....Branch Rickey's own company, American Baseball Cap, brought helmets into use. Phil Rizzuto was the first player to wear one, dating back to 1951, but the following year, on September 15, the entire Pittsburgh Pirate team wore them both at bat and in the field .... Now every player wears the helmet, most of them with earflaps. It was Brooks Robinson who first wore the earflap for added protection, and Brooks also had half the bill of his helmet removed for greater visibility.

....The cup-ended or hollowed-out bats were first introduced in Japan and admired there by Lou Brock. Jose Cardenal of the 1976 Cubs was the first American player to have his Louisville Sluggers so designed, feeling that it put more weight into the "meat" of the bat.

The "tape-measure home run" was born on April 17, 1953, when Mickey Mantle powered one 565 feet in Washington and Yankee public relation director Red Patterson actually borrowed a tape measure to count it off.

The baseballs themselves were made of horsehide until 1974, when Spalding switched to the more available cowhide, and in 1976 the Rawlings name first appeared on major-league baseballs.

....The weighted "doughnut" used by hitters in the on-deck circle was invented in 1968 by Elston Howard, then with the Red Sox.

....Instant Replay, now so commonly accepted, was first used at a local level when WPIX-TV in New York replayed the ruin of a no-hitter on July 17, 1959, with announcer Mel Allen asking director Jack Murphy to run the tape right there rather than wait for the postgame show. It showed Ralph Terry's no-hitter go down the drain as a base hit by Chicago's Jim McAhany fell in front of Norm Siebern in the ninth inning.

....The first color telecast was on August 11, 1951, with Brooklyn hosting Boston for a doubleheader in Ebbets Field, carried by NBC.

....[T]he first black coach [was] Jim Gilliam of Los Angeles in 1965 .... The first black umpire was the American League's Emmett Ashford in 1966. The first black manager was Cleveland's Frank Robinson in 1975. The first black general manager was Atlanta's Bill Lucas in 1977....

....Players like to make "curtain calls" after dramatic home runs these days, but that all started in 1961 after two of the most dramatic home runs in baseball history -- Roger Maris's sixtieth and sixty-first, both at Yankee Stadium. On both occasions, teammates forced the shy Maris to step out of the dugout to acknowledge the fans' cheers.

-- Marty Appel

"Noting the Milestones"

in The Armchair Book of Baseball II (Jim Thorn, ed.)

NOTE: Modern Milestones, Part I can be found in Issue #8.

3rd INNING

The Yankees Go (Far) East

The [New York] Yankees' season did not end with their defeat in the world series in 1955. Two weeks after the final series game the team embarked on a month-long goodwill tour of the Far East sponsored by the U.S. Government and Pepsi-Cola. The Yankees spent two weeks in Hawaii and then more than two weeks flying to Wake Island, the Philippines, Guam, and finally to Japan, playing twenty-four exhibition games before throngs of fanatical fans and admirers. Sixty or seventy thousand people attended each game, and wherever the Yankees went they were treated like visiting royalty, especially in baseball-crazy Japan, where two million people lined the streets of Tokyo to greet them.

Before they departed, most of the Yankees had not been enthusiastic about going. They had just completed a long, grueling season, but under [George] Weiss's thinly veiled threats of punitive action, all the players agreed to go except Phil Rizzuto, who refused to leave his pregnant wife behind. Those who went were thankful for the unique experience. Weiss allowed the players' wives to go, and John Kucks, Ed Robinson, and Andy Carey all got married the week before the trip so they could bring along their brides.

....The Yankees were playing the best professional talent in the Far East. When the tour ended, the Yankees returned with a 23-0-1 record. Though it was a pleasure trip, [Manager Casey] Stengel's primary consideration was nevertheless to win the ball games. That was the only way Stengel knew how to play.

The twenty-four game exhibition schedule enabled Stengel to prepare for 1956. He assessed the abilities of his rookies: [Elston' Howard, Kucks, and another young pitcher, Tom Sturdivant. All played exceptionally well, and the slider that Kucks learned from Jim Turner in japan made him the most effective pitcher on the tour. With Rizzuto back in the States, Gil McDougald kept kidding Stengel to let him play shortstop, and when Stengel finally relented, McDougald turned out to be as excellent a shortstop as he was a second- and third-baseman. In 1956 McDougald was named the All-Star American League shortstop, and Rizzuto was released. Andy Carey hit thirteen home runs to lead the Yankees and decided that he should be a home-run hitting pull-hitter, thus helping to ruin his career. The twenty-four game exhibition schedule enabled Stengel to prepare for 1956. He assessed the abilities of his rookies: [Elston' Howard, Kucks, and another young pitcher, Tom Sturdivant. All played exceptionally well, and the slider that Kucks learned from Jim Turner in japan made him the most effective pitcher on the tour. With Rizzuto back in the States, Gil McDougald kept kidding Stengel to let him play shortstop, and when Stengel finally relented, McDougald turned out to be as excellent a shortstop as he was a second- and third-baseman. In 1956 McDougald was named the All-Star American League shortstop, and Rizzuto was released. Andy Carey hit thirteen home runs to lead the Yankees and decided that he should be a home-run hitting pull-hitter, thus helping to ruin his career. Along the way the Yankees visited the Imperial Palace in Tokyo. They visited Hiroshima, where only ten years before the U.S. had ended the second world war by dropping an atomic bomb .... The team was introduced to Japanese Prime Minister Hatoyama. He asked several of the players if they had ever been to the Far East before. Hank Bauer, the ex-Marine, nodded his head yes.

"When was that?" Prime Minister Hatoyama asked.

"When I landed on the beach at Iwo Jima," Bauer said. There was an uncomfortable silence as the prime minister quickly changed the subject.

....In Japan the players didn't have to worry about the eagle eye of the American press, and they let their hair down more than usual. Stengel and some of the players left their wives behind and visited the geisha houses for a massage. The liquor flowed freely....

[Billy] Martin was the life of the party. While the team was in Tokyo, Billy and Mickey [Mantle] were in the bar of the hotel at about three in the morning, when Billy decided that he wanted to have a party. In each of the players' rooms the phones jangled in their cradles, awakening the occupants. It was Billy on the other end of the line. "There's a big fight in the bar," Martin yelled, "and Mickey's getting hit. Hurry." Mantle, standing behind Martin, was banging two chairs together and screaming, "Help, help!" By the time Martin had called the troops, the entire team was in the bar laughing and drinking, some of the men in their undershorts, some in kimonos .... The party went on for hours, and when it ended Don Larsen fixed perpetrators Martin and Mantle. He signed their names to every one of the bar checks.

There were also lighter moments during the games. Before each game the Yankees were given a cocktail party, and every once in a while a player would have one Scotch and soda too many, and funny situations would result. Against the Tokyo Giants Whitey Ford was pitching, and there was a runner on second base. Ford signaled for a pick-off at second which neither McDougald at short or Martin at second saw him give. Ford spun around and fired the ball to second, and when no one covered, the ball sailed toward center field and struck the second-base umpire, who was standing right behind the bag, on the forehead and ricocheted past right-fielder Hank Bauer, who was trying to work off a hangover. Bauer, who had no idea how the ball got into the outfield in the first place, started weaving after it as the runner lit for home. Gil McDougald, meanwhile, walked over to see if the beaned umpire was all right. McDougald looked at him standing there, arms crossed, poker-faced like the inscrutable Buddha .... Gil then walked to the mound to talk with his pitcher. "Whitey," Gil said, trying not to laugh, "that's the ... tip-off on you. When you can hit a guy dead center from sixty feet and you don't even leave a mark on him ...." Meanwhile, by the time Bauer finally ran down the ball and threw it back into the infield, the runner could have circled the bases twice.

-- Peter Golenbock

Dynasty: The New York Yankees, 1949-1964

4th INNING

The Bush Leaguer

{This article was written in 1909 -- ed.} A few years ago the Los Angeles team of the Pacific Coast League had need of a substitute first baseman. Frank Dillon, first baseman and team captain, had signed a contract to play with the Brooklyn club of the National League. Dillon was anxious to remain in California and did not report with the Eastern team for spring practice.

The manager..., looking about him for a substitute player, engaged a boy from a small college team in central California .... His face was unknown to the Southern [Division] baseball fans who immediately dubbed him a "bush leaguer" .... The youngster ... [nursed] an odd-shaped pancake glove; a battered relic contrasting sharply with his new flannel uniform and spiked shoes.

It was his first appearance in "organized baseball." Success meant a chance to earn money; failure meant a ticket back to the prune orchards of Santa Clara County.

The gong clanged, announcing the opening of the game. The umpire drew a paper from his pocket, showed it to Dillon, and the captain and first baseman slowly left the field. He had been informed that every game in which he played would be declared forfeited. Baseball magnates have many ways of protecting themselves in business deals; Dillon had signed with Brooklyn and Brooklyn meant to have him.

The long-legged country boy arose and ambled out to Dillon's old position. The stands were in an uproar. Dillon had been the idol of the baseball public; the best first baseman in the league .... The contagion spread to the Los Angeles players, not one of whom had confidence in the raw college boy, thus thrust into an important position.

It would be hard to imagine a more unfortunate first appearance. The game opened with a rush. The first batter smashed a ground ball at the Los Angeles shortstop and tore down the line to first base. Mechanically the shortstop raced over, dropped his gloves in front of the ball, and faced about to make the throw to first base. Instead of Dillon, there was the "bush league kid" on the bag.

The base runner was a fast man; in the twinkling of an eye the thing had been done -- the panic was working. Instead of the perfect line "peg" to first base, the shortstop threw fully eight feet outside the bag and correspondingly high, shooting the ball with the speed of a rifle bullet. It would have been a vicious throw for a right-hander to care for, even though on his glove-hand side; the bush league boy was a left-handed player and wore the glove on his right hand ....

With the fraction of a second in which to decide what to do, the country boy whirled with his back to the diamond, hooked the spikes of his left shoe in the bag, and thrust out a long right arm for a back-hand catch. The runner was beaten [by] a stride on a circus catch which few big-leaguers would care to attempt.

After the cheering, the bleacherites decided that it had been a blind, back-hand stab or a lucky accident. Twenty minutes later every man inside the grounds knew that he was seeing first base played as no youngster had ever played it before .... The boy covered the ground with great loose-jointed strides, dug up impossible ground balls beyond the reach of an ordinary fielding first baseman, picked line drives out of the air, nipped bunts ten feet from the plate, caught advancing runners, and capped the climax by starting and finishing a double play thought to be possible with only one first baseman in America, Fred Tenney of the Nationals. There was but one verdict at the end of the game; the boy was the greatest first baseman ever seen on the Pacific Coast ....

On the next opening day, the youngster wore a New York [Highlanders] uniform .... In less than a week Hal Chase was the baseball sensation of the season, and baseball critics burned up columns in an attempt to analyze his method of playing his position. Chase ... makes his plays by some unerring instinct which must have been born in him, and when it comes to handling bad throws at first base, there never was a player like him .... Other men have had more years of experience; many players are better at post-mortem analysis of a baseball problem, but when a ball is hit down to Hal Chase, you will see the bleachers come up as one man. The fans never know what he is going to do with the ball once he gets it, but they do know that there will be no fumbling or "booting," but a chain-lightning play directed at the one spot where the most damage can be done. Chase is the personification of baseball by instinct and the most popular first baseman the country has ever seen. On the next opening day, the youngster wore a New York [Highlanders] uniform .... In less than a week Hal Chase was the baseball sensation of the season, and baseball critics burned up columns in an attempt to analyze his method of playing his position. Chase ... makes his plays by some unerring instinct which must have been born in him, and when it comes to handling bad throws at first base, there never was a player like him .... Other men have had more years of experience; many players are better at post-mortem analysis of a baseball problem, but when a ball is hit down to Hal Chase, you will see the bleachers come up as one man. The fans never know what he is going to do with the ball once he gets it, but they do know that there will be no fumbling or "booting," but a chain-lightning play directed at the one spot where the most damage can be done. Chase is the personification of baseball by instinct and the most popular first baseman the country has ever seen. -- Charles E. Val Loan

"Baseball as the Bleachers Like It"

in Baseball: A Literary Anthology (Nicholas Dawidoff, ed.)

Unfortunately, "Prince Hal" set the AL all-time mark for errors by a first baseman with 285, and people began to suspect early on that he was too talented to be making so many miscues unless it was on purpose. In 1910, New York manager George Stallings accused Chase of throwing games; the end result was that Stallings lost his job and Chase became player-manager for one year. In 1918, when Chase was with the Cincinnati Reds, skipper Christy Mathewson suspended him for throwing games. In the end, Chase was barred for life from playing major league baseball. -- ed.

5th INNING

Rod Kanehl: The Mets in '62

I really enjoyed that spring training with the Mets in '62. It was great. Our hitting coach was Rogers Hornsby. Nobody could hit like Hornsby and Casey [Stengel] would tell us that, but Hornsby was just a figurehead. He would make comments about hitting, but he didn't coach anybody. I really enjoyed that spring training with the Mets in '62. It was great. Our hitting coach was Rogers Hornsby. Nobody could hit like Hornsby and Casey [Stengel] would tell us that, but Hornsby was just a figurehead. He would make comments about hitting, but he didn't coach anybody.Hornsby's theory of hitting was to hit up the middle, which is one theory .... Casey's theory of hitting was to put the ball in play down the lines. Here was Casey's thinking: Where do they put the worst fielding ballplayers? On the corners and in left and right field ....

I never saw him purposely put someone in a position to look bad. Because he always tried to create a value. He would play marginal players, players he knew they were trying to get rid of, in positions so they could look good. He always tried to increase your value.

....I was the only American Leaguer drafted and the only guy out of the New York Yankee chain. Because it was National League expansion, the only players offered were National Leaguers. And so no one else knew anything about Stengel except me.

Here were old pros like Gil Hodges, Don Zimmer, Roger Craig, Clem labine, Joe Ginsberg, Frank Thomas, Richie Ashburn, Gus Belkl, and here I am, coming from Double A, and when Casey started teaching his system, he knew I was the only one who knew what he was talking about.

So he started out and went through his routine. He intended to teach the Mets the Yankee system, and he said, "Kanehl, go to first base and show them how to lead off." Then I'd go to second. "Kanehl, show them how to lead off second." We'd go down to third. "Kanehl show them how you take the signs." We went to bunting. "Kanehl, show them how to bunt." Those guys were veterans. They were thinking, who is this f****** Kanehl?....

"I grabbed a bat and went up to the plate to bunt. Roger Craig was on the mound and he was supposed to be lobbing the ball in to me so I could show them how to bunt. Well, he turned one loose and knocked me on my ass! He decked me! And I grabbed the ball and jumped up and fired it right back at him. I said, "Get the ball over, Meat" ....

And so I caught their eye, and during batting practice I would always work on my skills in the outfield, playing the ball off the bat. These ... veterans would be standing around, telling war stories, about the National League. One time Ashburn, Bell, Frank Thomas and Roger Craig were standing around in a little circle, and a ball was hit in their direction. I bolted over for it, and I called it, and Ashburn stepped out of the circle and said, "I got it," and he dropped it. I told him, "If you call it, catch it." That's the way I was. Because I was out there working, and they were just farting around. Later Ashburn told me, "I knew you were going to make it."

....At the last moment they sent Joe Christopher to Syracuse, and that made room on the roster for me. Ted Lepcio had been penciled in as the utility man. But I could also play outfield, and I could bunt better and probably hit a little bit better. So I got the last spot.

....We lost the opener, but when we came back from St. Louis, they had a ticker tape parade down Broadway, and that was great. We ended up at City Hall, and Mayor Wagner was on the steps, and he gave Casey the key to the city. It was quite an experience.

When the season started we were full of confidence. We had veterans at every position. Gus Bell, Richie Ashburn and Frank Thomas were in the outfield, and Hobie Landrith, the first player drafted, caught. In the infield Don Zimmer was the third baseman, and Felix Mantilla was at short, Charlie Neal at second, and Gil Hodges at first ....

....But we had absolutely no pitching. And we had no bullpen. We had one of the finest relief pitchers in the National League, Roger Craig, as a starter. He would have set all kinds of relief records had he been able to be used as a reliever. Roger was a good five-inning pitcher, had a good pickoff move, and he had a good sinker/slider. He could come in and get a ground ball, and boom, it's over. He was perfect for relief. But we had to use him as a starter.

We would be in the game through the sixth or seventh inning, and then it was over. We lost our first nine games, but we were in a lot of those games. We just didn't get off the ground.

Even though we lost, we were still upbeat .... A lot of people identified with the Mets -- underdog types, not losers -- quality people who weren't quite getting it together. And Casey was always a draw. Casey would fill the [newspaper] columns .... And you've got to do that in New York. You have to give them something to write about. Casey always had print for the writers, and that's why the writers would go along with him ....

We started the '62 season with nothing but veterans, because that's what [General Manager] George Weiss wanted. He wanted to attract the National League crowd. And Casey didn't want that at all.

I was hitting .330 in early May. I went up to Casey in his office in the Polo Grounds, and I said, "I'm hitting .330, leading the team in hitting. How come I'm not playing regularly?" And he asked me how much I was making. I said, "Eight thousand." He said, "You're not making enough money to be playing regular." He said, "I'm going to give the Old Man upstairs," meaning Weiss, "the walking dead till he's sick of it" ....

And then Hodges went down, and Zimmer was gone, and we traded Bell to Milwaukee. Before the season was over, he started playing the younger guys.

-- Rod Kanehl

in Amazin': The Miraculous History of New York's

Most Beloved Baseball Team (Peter Golenbock)

6th INNING

Stats: Top (25) Single-Season RBI

Hack Wilson (CHC), 1930, 191 Hack Wilson (CHC), 1930, 191 Lou Gehrig (NYY), 1931, 184

Hank Greenberg (DET), 1937, 183

Jimmie Foxx (BOS), 1938, 175

Lou Gehrig (NYY), 1927, 175

Lou Gehrig (NYY) 1930, 174

Babe Ruth (NYY), 1921, 171

Hank Greenberg (DET), 1935, 170

Chuck Klein (PHI), 1930, 170

Jimmie Foxx (PHI), 1932, 169

Joe DiMaggio (NYY), 1937, 167

Sam Thompson (DET), 1887, 166

Lou Gehrig (NYY), 1934, 165

Manny Ramirez (CLE), 1999, 165

Al Simmons (PHA), 1930, 165

Sam Thompson (DET), 1895, 165

Babe Ruth (NYY), 1927, 164

Jimmie Foxx (PHI), 1933, 163

Babe Ruth (NYY), 1931, 163

Hal Trosky (CLE), 1936, 162

Sammy Sosa (CHC), 2001, 160

Lou Gehrig (NYY), 1937, 159

Vern Stephens (BOS), 1949, 159

Ted Williams (BOS), 1949, 159

Hack Wilson (CHC), 1929, 159

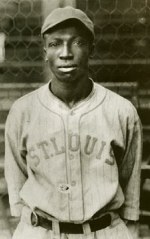

IMAGE: Hack Wilson (1923-34)

7th INNING

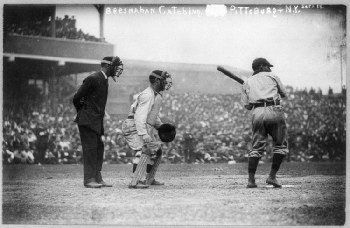

Year in Review: 1908

The 1908 season was the biggest year for pitching in a decade of pitchers' years. Both leagues batted .239, both record lows. Only one of the 16 major league pitching staffs, the Yankees', had an ERA over 3.00. Seven pitchers threw no-hitters and seven of the all-time 50 lowest season ERAs came in 1908. Individual milestones included Ed Walsh's 40 wins (the second greatest total in history) and 464 innings pitched (the most ever); Christy Mathewson's 37 wins; Addie Joss's 1.16 ERA (seventh-lowest in history); and Cy Young's 1.26 ERA (the tenth-best).

This wealth of pitching produced two of the closest, most exciting, and most controversial pennant races of all time. A three-team NL race between Chicago, Pittsburgh, and New York hinged on the still-talked-about Fred Merkle blunder, which occurred in a September 23 game between the Giants and the Cubs.

The score was tied 1-1 and the sun was setting over the Polo Grounds in New York. Fred Merkle, a rookie substitute, was standing on first and Moose McCormick occupied third with two outs in the bottom of the ninth, when Giants shortstop Al Bridwell singled to center. Thinking the game was won, and with a crowd of happy fans swarming the infield, Merkle bypassed second base and made for the New York clubhouse. But Chicago second baseman Johnny Evers got the attention of the umpire who, after seeing Evers tag second base with a ball (there was some dispute over whether it was actually the game ball), declared Merkle forced out at second, nullifying the winning run.

This ignited a storm of protests, counter-protests, and league hearings. Finally, NL president Harry Pulliam ruled that the game would be replayed after the season if it proved to have a bearing on the pennant race. Unfortunately for the Giants, it did. New York and Chicago finished in a tie, which was broken when Chicago's Three Finger bBown defeated Mathewson 4-2 in the make-up game. The Cubs finished with a 99-55 record, 1 game up on the Giants and Pirates, both at 98-56.

While the 1908 Cubs exhibited their usual combination of great pitching and team defense, the Giants were carried by Christy Mathewson, who led the league in wins, games, complete games, strikeouts, and ERA. He threw a league-high 11 shutouts and recorded five saves, pitching in a dozen games out of the bullpen between starts. Once again, Pittsburgh was the Honus Wagner Show, as Wagner won his usual batting title at .354 and led in on-base average at .410 and slugging average at .542. He also made a clean sweep of six other key offensive categories: hits, RBI, doubles, triples, total bases, and stolen bases.

In the AL, a four-team race came down to the wire, with Detroit (90-63) finally slipping past Cleveland (90-64) by .004 percentage points, the smallest margin of victory in AL or NL history. Chicago finished 1-1/2 back and St. Louis faded late to end up 6-1/2 behind.

As in 1907, Ty Cobb and Sam Crawford led the AL in nearly everything. Cobb won the batting title at .324 and was No. 1 in hits, doubles, triples, total bases, RBI, and slugging. Crawford led in home runs and was second in runs, RBI, hits, total bases, batting, and slugging.

-- David Nemec, et al.

The Baseball Chronicle

IMAGE: Roger Bresnahan, catching a game in Pittsburgh in 1908.

8th INNING

The 1908 World Series

Chicago Cubs (4) v Detroit Tigers (1)

October 10-14

West Side Grounds (Chicago), Bennett Park (Detroit)

For the second straight year, [Ty] Cobb's team was humiliated in the World Series, this time 4-1. Cubs batters hit .293 off Tigers pitching, while [Three Finger] Brown's 0.00 ERA in 11 innings paced the Chicago staff to a 2.60 ERA. Cobb's personal performance improved, as he batted .368 with four RBI and a pair of stolen bases. (The Baseball Chronicle, David Nemec, et al.)

Ty Cobb in action in the 1908 World Series

Game 1: Chicago 10, Detroit 6

Game 2: Chicago 6, Detroit 1

Game 3: Detroit 8, Chicago 3

Game 4: Chicago 3, Detroit 0

Game 5: Chicago 2, Detroit 0

CHICAGO: Mordecai Brown(p), Frank Chance (1b), Johnny Evers (2b), Solly Hofman (of), Del Howard (ph), Johnny Kling (c), Orval Overall (p), Jack Pfiester (p), Ed Reulbach (p), Frank Schulte (of), Jimmy Sheckard (of), Harry Steinfeldt (3b), Joe Tinker (ss). Mgr: Frank Chance

DETROIT: Ty Cobb (of), Bill Couglin (3b), Sam Crawford (of), Bill Donovan (p), Red Downs (2b), Davy Jones (ph), Ed Killian (p), Matty McIntyre (of), George Mullin (p), Charley O'Leary (ss), Claude Rossman (1b), Germany Schaefer (2b, 3b), Boss Schmidt (c), Ed Summers (p), Ira Thomas (c), George Winter (p). Mgr: Hughie Jennings

Chicago's Mordecai "Three Finger" Brown started two of the four games and had a series ERA of 0.00. Joe Tinker's Game 2 homer was the first hit in a world series since 1903's Game 2. Cubs pitcher Orval Overall struck out four Detroit batters in a single inning of Game 5.

9th INNING 9th INNINGPlayer Profile: James Thomas "Cool Papa" Bell

Born May 17, 1903 (Starksville, MS)

Died March 7, 1991 (St. Louis, MO)

Inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1974

Played for: St. Louis Stars (1922-31), Detroit Wolves (1932), Kansas City Monarchs (1932, 1934), Homestead Grays (1932, 1943-46), Pittsburgh Crawfords (1933-38), Memphis Red Sox (1942), Chicago American Giants (1942), Detroit Senators (1947), Kansas City Stars (1948-50).

Won the Mexican League Triple Crown in 1940 when his .437 average bested fellow Hall of Famer Martin Dihigo.

James Bell was a pitcher early in his career but later a great center fielder for most of his tenure in Negro League baseball, a career that lasted from 1922 to 1946 .... [He] was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1974 [and] is most famous for his legendary speed, which was often described in colorful stories ... He is...supposed to have once hit a ball up the middle and was hit by the ball as he slid into second base. Although [such] stories may be more lore than truth, the fact is that the 5-foot-11, 150-pound Bell ... was probably the fastest man in Negro League baseball -- and likely in all of baseball at the time....

....Bell broke into Negro League baseball at age 19 in 1922 with the St. Louis Stars, where he got his nickname for his ability to play under pressure -- in particular, one time when he struck out the great Oscar Charleston. He was a perennial player in the East-West All-Star Game, and in the 1935 game scored from second on an infield hit by Boojum Wilson in a spectacular play....

Bell remained one of the best hitters in Negro League baseball in his later years, batting .373 in 1945 and .412 the following year, according to some reports. Bell was offered a chance to play major league baseball with the St. Louis Browns in 1951 when he was nearly 48 years old but turned it down. Browns owner Bill Veeck said of Bell: "Defensively, he was the equal of Tris Speaker, Joe DiMaggio, or Willie Mays" ....

Bell said he stole 175 bases in 200 games one year, and one report had him running around the bases in 12 seconds .... Records show that Bell is believed to have batted .342 during his Negro League career .... In St. Louis, Bell played with such ... greats as Willie Wells and Mule Suttles. In Pittsburgh he played with [Satchel] Paige, Charleston, and Josh Gibson. Bell also played winter baseball in Cuba, where he reportedly hit .316 lifetime, and in Mexico, where he batted .367 during his career there....

In 1937 Bell was one of a group of Negro players recruited by Dominican Republic dictator Rafael Trujillo to play one season in his country as part of the baseball political battle going on there. He also played on a team in the California Winter League in 1935 -- the only black team in the league that year, playing on a squad known as the Philadelphia Giants, along with Suttles and Turkey Stearnes. He also played for a barnstorming team that competed against white teams ... and batted .392 against them. He spent his final years in baseball managing a team ... sometimes known as the Kansas City Stars .... Some of the players he managed on that team included Ernie Banks and Elston Howard.

Bell retired and worked for the city of St. Louis as a watchman and janitor until retiring in 1973. A month after his wife, Clara, passed away in 1991, Bell suffered a heart attack ... and died a week later.

-- Thom Loverro

The Encyclopedia of Negro League Baseball

EXTRA INNINGS

They Played the Game

Tommie Agee

(1962-73)

Only Bobby Bonds has a worse strikeout ratio among leadoff men than Agee who, while with the New York Mets, had five consecutive years with more than 100 strikeouts. His season high was 156 in 1970. Agee did, however, make two spectacular outfield grabs in the World Series that matched the Miracle Mets against Baltimore, and he was a two-time All-Star.

BORN 9.9.42, Magnolia, AL .255, 130, 433 All-Star 1966, 1967 1966 AL ROY

1966 AL Gold Glove, 1970 NL Gold Glove

Sparky Anderson

(1959, 1970-1995)

The only manager to win world championships for teams in both leagues. Managed Cincinnati and Detroit for 25 years while, as a player, appeared as a regular only one year (1959), with the Phillies. Under Anderson the Big Red Machine won five division titles, four pennants and two World Series between 1970-1978. His Tigers won a world championship in 1984 and a division title in 1987, giving him a record (tied by Bobby Cox) for winning the most pennant playoff series (5).

"Captain Hook" BORN 2.22.34, Bridgewater, SD

Mgr record 2194-1834 2 NL Championships 3 World Series Championships

Tim Keefe

(1880-93)

Hall of Famer Keefe pitched in three major leagues during his 14-year career, and won games in 47 different major league parks -- an all-time record. Keefe racked up a total of 342 wins. His 19 consecutive wins in 1888 with the New York Giants was a single-season record until 1912, when it was broken by Rube Marquand -- who also played for the Giants. That year Keefe led the NL in wins, ERA, strikeouts and shutouts. In 1889, the year owners instituted a pay scale, Keefe earned $5,000, the highest salary in the NL. He helped establish the Players' League in 1890.

BORN 1.1.1887 (Cambridge, MA) 1888 NL Triple Crown

John Paciorek

(1963)

In the final game of the 1963 season, Houston's John Paciorek went 3-for-3 with two walks, three RBI, and four runs scored in his first ML game. But Paciorek never played in another ML game.

BORN 2.11.45, Detroit, MI 1.000, 0, 3

Cy Seymour

(1896-1913)

Led the NL with 239 strikeouts in 1898, but after the 1899 season his arm gave out and he became one of the game's best hitters, coming close to winning the NL's Triple Crown in 1905 with .377, 8, 121 marks.

BORN 12.9.1872 (Albany, NY)

THIS MATERIAL IS REPRODUCED FOR NON-PROFIT EDUCATIONAL AND SCHOLARLY PURPOSES ONLY, WHICH COMPLIES WITH THE DOCTRINE OF FAIR USE AS EXPRESSED IN THE COPYRIGHT ACT OF 19 OCTOBER 1976, EFFECTIVE 1 JANUARY 1978 (TITLE 17 OF THE UNITED STATES CODE, PUBLIC LAW 94-553, 90 STAT. 2541

|