9 Innings 9 InningsA Baseball History Reader

J. Manning, Editor

|

||

Issue # 7: September 26, 2006

19th Century Baseball Cards ... Baseball According to Giamatti ... The East-West Game ... Bucky F****** Dent ... Sam Crawford: The O's, Wee Willie, and Dummy Hoy ... Stats: Record Holders (Pitching) ... Year in Review: 1906 ... The 1906 World Series ... Player Profile: James Creighton ... They Played the Game

|

||

"A game of great charm, in the adoption of mathematical measurements to the timing of human movements, the exactitudes and adjustments of physical ability to hazardous chance. The speed of the legs, the dexterity of the body, the grace of the swing, the elusiveness of the slide -- these are the features that make Americans everywhere forget the last syllable of a man's last name or the pigmentation of his skin."

-- Branch Rickey

1st INNING

19th Century Baseball Cards

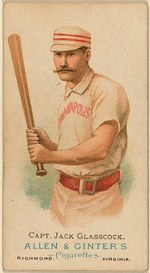

Baseball cards are an important part of any 19th-century collection, especially those from 1886 to 1890, a period collectors often call "the first golden age" of baseball-card production. More than 25 issues, encompassing thousands of cards, flooded the marketplace. Produced primarily by cigarette and tobacco companies and marketed as inserts with their goods, the intriguing swatches of cardboard featured either state-of-the-art color lithography or handsome sepia-toned photographs of the most notable players of the era.

The first major issue of baseball cards was produced in 1887 by the tobacco firm of Goodwin & Company and distributed in packages of Old Judge cigarettes They have an American Card Catalog ... designation of N172 (the "N" signifies 19th century in the ACC, and the 172 is an arbitrary number assigned to that card issue. These small cards consisted of sepia toned photographs glued onto thick cardboard mounts. They depicted well over 500 different subjects, including all the stars of the day from both the major and minor leagues. Because nearly all of the players appeared in multiple poses, there are more than 2,000 cards from this issue .... The most sought-after subjects include Cap Anson, Mike Kelly, Buck Ewing, John Ward, Connie Mack, John Clarkson, Don Brouthers, Pud Galvin, Amos Rusie, Harry Wright, Tim Keefe, and Charles Comiskey. The first major issue of baseball cards was produced in 1887 by the tobacco firm of Goodwin & Company and distributed in packages of Old Judge cigarettes They have an American Card Catalog ... designation of N172 (the "N" signifies 19th century in the ACC, and the 172 is an arbitrary number assigned to that card issue. These small cards consisted of sepia toned photographs glued onto thick cardboard mounts. They depicted well over 500 different subjects, including all the stars of the day from both the major and minor leagues. Because nearly all of the players appeared in multiple poses, there are more than 2,000 cards from this issue .... The most sought-after subjects include Cap Anson, Mike Kelly, Buck Ewing, John Ward, Connie Mack, John Clarkson, Don Brouthers, Pud Galvin, Amos Rusie, Harry Wright, Tim Keefe, and Charles Comiskey.....In 1887 and 1888, the Allen & Ginter Company produced three full-color 50-card sets of sports champions, including baseball stars. These sets are extremely popular with collectors today. The first, catalogued as N28, features 10 baseball players, six of whom are members of the Hall of Fame ....

Many other issues appeared in the last four years of the 1880s, among them the Kimball, Goodwin's Champions, and Buchner gold coin releases. Each of these issues featured beautiful color images. In the mid-1890s, Mayo and Company issued a 48-card set, designated N300, with sepia portraits of many of the day's stars. They are classics of the period.

Many collectors try to obtain a single example of the era's scarcer issues, which include Lone Jack, Yum Yum, Kalamazoo Bats, S.F. Hess, and G&B chewing gum (one of the few period issues that is not tobacco-related.) Perhaps the most popular of these was the Kalamazoo Bats, issued by Charles Gross and cataloged as N690. This large issue of about 50 cards can be divided into four groups. The first three feature shots of individual players on the Philadelphia Athletics, the New York Giants, and the New York Metropolitans. The fourth contain full-team poses .... Gross also issued a group of even larger cabinet images. One of these, an image of baseball pioneer Harry Wright, is extremely rare and particularly desirable.

Extremely rare card issues, such as Four Base Hits, Just So, and the Large Gypsy Queens, represent a formidable challenge to collectors looking for just a single example. Two of the great rarities of this group are the Four Base Hits collectible of legendary player Mike Kelly, of which only two examples are known to exist, and the Just So card of Cy Young .... This was Young's first appearance on a baseball card, and there is only one example of the immortal pitcher's Just So card known to exist. Cards such as these are the stuff of collecting legend. They may never come up for sale, but the diehard collector lives for the evere-tantalizing possibility of acquiring one.

-- Stephen Wong

Smithsonian Baseball

2nd INNING

Baseball According to Giamatti

Genteel in its American origins, proletarian in its development, egalitarian in its demands and appeal, effortless in its adaptation to nature, raucous, hardnosed, and glamorous as a profession, expanding with the country like fingers unfolding from a fist, image of a lost past, evergreen reminder of America's best promises, baseball fits and still fits America. It fits so well because it embodies the interplay of individual and group that we so love and because it conserves our longing for the rule of law while licensing our resentment of lawgivers.

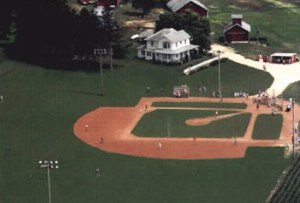

....Law -- defined as a complex of formal rules, agreed-upon boundaries, authoritative arbiters, custom, and a set of symmetrical opportunities and demands -- is enshrined in baseball. Indeed, the layout of the field shows baseball's essential passion for and reliance on precise proportions and clearly defined limits, all the better to give shape to energy and provide an arena for equality and expression. The pitcher's mound is comprised of a pitcher's rubber, 24 inches by 6 inches, elevated in the middle of an 18-foot circle; the rubber is 60 feet 6 inches from home plate; the four base paths are 90 feet long; the distance from first base to third, and home plate to second base, is 127 feet 3-3/8 inches; the pitcher's rubber is the center of a circle, described by the arc of the grass behind the infield from foul line to foul line, whose radius is 95 feet; from home plate to backstop, and swinging in an arc, is 60 feet. On this square tipped like a diamond containing circles and contained in circles, built on multiples of three, nine players play nine innings, with three outs to a side, each out possibly composed of three strikes. Four balls, four bases break (or is it underscore?) the game's reliance on "threes" to distribute an odd equality, all the numerology and symmetry tending to configure a game unbounded by that which bounds most sports, and adjudicates in many, Time. ....Law -- defined as a complex of formal rules, agreed-upon boundaries, authoritative arbiters, custom, and a set of symmetrical opportunities and demands -- is enshrined in baseball. Indeed, the layout of the field shows baseball's essential passion for and reliance on precise proportions and clearly defined limits, all the better to give shape to energy and provide an arena for equality and expression. The pitcher's mound is comprised of a pitcher's rubber, 24 inches by 6 inches, elevated in the middle of an 18-foot circle; the rubber is 60 feet 6 inches from home plate; the four base paths are 90 feet long; the distance from first base to third, and home plate to second base, is 127 feet 3-3/8 inches; the pitcher's rubber is the center of a circle, described by the arc of the grass behind the infield from foul line to foul line, whose radius is 95 feet; from home plate to backstop, and swinging in an arc, is 60 feet. On this square tipped like a diamond containing circles and contained in circles, built on multiples of three, nine players play nine innings, with three outs to a side, each out possibly composed of three strikes. Four balls, four bases break (or is it underscore?) the game's reliance on "threes" to distribute an odd equality, all the numerology and symmetry tending to configure a game unbounded by that which bounds most sports, and adjudicates in many, Time.The game comes from an America where the availability of sun defined the time for work or play -- nothing else. Virtually all our other sports reflect the time clock, either in their formal structure or their definition of a winner. Baseball views time as daylight and daylight as an endlessly renewable natural resource; it may put a premium on speed, of throw or foot, but it is unhurried. Daytime, like the water and forests, like the land itself, was assumed to be ever available. When it was not, the work of playing ceased. Until, that is, the lights in stadiums brought day to night and let the day worker watch (or engage in) play in the false sun of the arc light.

The point is, symmetrical surfaces, deep arithmetical patterns, and a vast, stable body of rules ensure competitive balance in the game and show forth a country devoted to the ideals of equality of treatment and opportunity; a country whose deepest dream is of a divinely proportioned and peopled green garden enclosure .... Baseball's essential rules for place and for play were established, by my reckomning, with almost no exceptions of consequence, by 1895. By today, the diamond and the rules of play have the character of Platonic ideas, of preexistent immutabilities that encourage activity, contain energy, and like any set of transcendent ideals, do not change. The image of the place for play, varied in reality, now often domed or carpeted, lit up at night, but unchanged in our mind's eye, is a shared image across America. In the lore of a society whose mobility has always been one of its distinguishing features, the baseball field is an image of home.

....The hunger for home makes the green geometry of the baseball field more than simply a metaphor for the American experience and character. The baseball field and the game that sanctifies boundaries, rules, and law, and appreciates cunning, theft and guile; that exalts energy, opportunism, and execution, while paying lip service to management, strategy, and long-range planning, is finally closer to an embodiment of American life than to the mere sporting image of it.

....[Baseball] renews itself with every pitch, every game, every season. Baseball is best played in the sun, on grass, but it can also, like literature, be played in the head. And there it lasts longest, and never loses its abiding innocence. There, the gap between promise and performance disappears.

-- A. Bartlett Giamatti

Foreword, The Armchair Book of Baseball (John Thorn, ed.)

3rd INNING

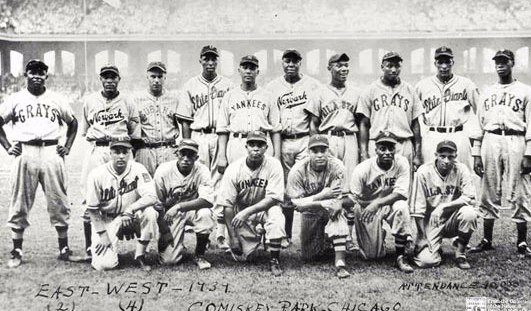

The East-West Game

The East-West Game was the Negro League's All-Star Game. It was started by Gus Greenlee, owner of the Pittsburgh Crawfords, in 1934, the same year major league baseball began its All-Star Game. It was played in Comiskey Park in Chicago ... and pitcher Bill Foster, representing the East, beat Lefty Streeter, representing the West, 11-7. The players were selected through voting by fans in black newspapers. The game would sometimes draw as many as 50,000 fans and outdrew the major league All-Star Game in 1938, 1942, 1943, 1946 (two East-West Games were held in 1946, the second at Griffith Stadium in Washington), and 1947. In his autobiography, I Was Right on Time, Negro Leaguer Buck O'Neil said that playing in an East-West Game "was something very special. That was the greatest idea Gus ever had, because it made black people feel involved in baseball like they'd never been before. While the big leagues left the choice of players up to the sportswriters, Gus left it up to the fans .... That was a pretty important thing for black people to do in those days, to be able to vote, even if it was just for ballplayers, and they sent in thousands of ballots .... Right away it was clear that our game meant a lot more than the big league game. Theirs was, and is, more or less an exhibition. But for black folks, the East-West Game was a matter of racial pride. Black people came from all over Chicago every year -- that's why we outdrew the big-league game some years, because we always had 50,000 people, and almost all of them were black people .... The weekend was always a party. All the hotels on the South Side were filled. All the big nightclubs were hopping."

Monte Irvin, in Mark Ribowsky's book A Complete History of the Negro Leagues, called the East-West games "a joyful experience. They put red, white and blue banners up all over the park, and a jazz band would play in between innings .... The games were good. The players were great. If you could have picked one all-star team from the two squads, it surely could have rivaled any white major league all-star team of all time. That team would have been as good as any all-star team that's ever played."

Some of the other great Negro League players who were voted to play in the East-West Game included Josh Gibson, Oscar Charleston, Satchel Paige, Martin Dihigo, Cool Papa Bell, Willie Wells, Ray Dandridge, Mule Suttles, and O'Neil. The game, in a watered-down version after the integration of major league baseball, continued until the final game was played in 1963 in Kansas City.

-- Thom Loverro

The Encyclopedia of Negro League Baseball

4th INNING

Bucky F****** Dent

In Boston, they add an unprintable middle name to Bucky Dent.

The Yankees acquired Dent early in the 1977 season as owner George Steinbrenner, desiring an All-Star at every position, grew weary of Fred "Chicken" Stanley and Jim Mason. Oscar Gamble went to the White Sox for Dent and hit 31 home runs despite playing half his games in a pitcher's park, teaming with "Pitch at Risk to" Richie Zisk, Ralph "Roadrunner" Garr, and the immortal Eric Soderholm to help Chicago make an improbable run at the AL West title. Dent hit .247, a nine-point improvement over Stanley.

Dent missed part of 1978 with a leg injury and spent most of the season in the .240s again. He was by far the weakest link in a Yankees lineup loaded with dangerous clutch hitters like Chris Chambliss, Willie Randolph, Craig Nettles, Reggie Jackson, Mickey Rivers, Lou Piniella, and Thurmon Munson. When the prettyboy shortstop came to bat in Yankee Stadium, grown men muttered while the teenage girls squealed.

The 1978 Yankees had fallen 14-1/2 games behind the Boston Red Sox in early August before making perhaps the greatest late-season charge of all time. On September 7, having won 12 of 14, the Yankees came to Fenway Park only 4 games behind Boston. They call what happened the "Boston Massacre," as New York left town in a first-place tie, having outscored the Red Sox 42-9. But ... the Red Sox did not go quietly. Down 3-1/2 games, Boston beat New York in the final game of a three-game series in Yankee Stadium and slowly began to crawl back into contention. They tied the Yankees on the final game of the season ....

The one-game playoff took place in Fenway Park, where 16-game winner Mike Torrez faced off against the league's best pitcher, 24-3 Ron Guidry and his nine shutouts. Carl Yastrzemski put the Red Sox in front with a line-drive home run just inside the right-field pole, but Mike Torrez carried a 2-0 lead into the seventh inning. With two men on, Red Sox manager Don Zimmer let Torrez face the weak-hitting Dent. He had only 16 extra-base hits and 37 RBI all season, so Boston fans were counting the number-nine hitter as an easy out before Mickey Rivers and the top of the lineup came around again.

The Sox and their fans had to be feeling even more confident when Dent fouled a ball straight down onto his foot and crumpled in a heap in the batter's box. As Dent tried to walk off the pain, few noticed Mickey Rivers handing Dent a new bat, telling him that he'd spotted a crack in the one the shortstop had been using. Back in the box but down 0-2, Dent responded by lifting a long fly ball that settled into the screen mere inches above the Green Monster in left field to put the Yankees ahead 3-2.

New York went ahead 5-2, the fifth run coming on a majestic Reggis Jackson home run into the seats in center field. The Yankees brought in relief ace Rich Gossage in the bottom of the seventh, and he kept things interesting. Boston closed to 5-4, and put the winning runs on in the bottom of the ninth before Gossage got Carl Yastrzemski to pop up to Craig Nettles at third base to end the game.

The Dodgers' faces bore the same looks of stunned disbelief when Bucky Dent went on to lead the Yankees to their second consecutive championship, hitting .417 and knocking in 7 runs, 3 in the Game 6 finale in L.A.

Don Zimmer later acknowledged having nightmares about Bucky Dent's fly-ball home run throughout the 1978 off-season. It could only make matters worse when, years later, Mickey Rivers admitted that Dent's bat didn't have a crack in it after all. He was just looking for an excuse to hand the light-hitting shortstop a corked bat!

-- Doug Myers & Bryan Dodd

Batting Around

5th INNING

Sam Crawford: The O's, Wee Willie, and Dummy Hoy

Kid Gleason used to be on that old Baltimore Orioles team in the 1890's. You know, with Willie Keeler and [John] McGraw and Dan Brouthers and Hughie Jennings, who later became our manager at Detroit. That whole crew moved over to Brooklyn later. I played against those guys when I came up with Cincinnati, in 1899, and let me tell you, after you'd made a trip around the bases against them you knew you'd been somewhere. They'd trip you, give you the hip, and who knows what else. Boy, it was rough. There was only one umpire in those days, see, and he couldn't be everywhere at once.

Ned Hanlon used to manage that Baltimore club, but those old veterans didn't pay any attention to him. Heck, they all knew baseball inside out. You know, ballplayers were tough in those days, but they were real smart, too. Plenty smart. There's no doubt at all in my mind that the old-time ballplayer was smarter than the modern player. No doubt at all. That's what baseball was all about then, a game of strategy and tactics, and if you played in the Big Leagues you had to know how to think, and think quick, or you'd be back in the minors before you knew what in the world hit you.

Now the game is all different. All power and lively balls and short fences and home runs. But not in the old days. I led the National League in home runs in 1901, and do you know how many I hit? Sixteen. That was a helluva lot for those days. Tommy Leach led the league the next year -- with six! In 1908 I led the American League with only seven. Do you know the most home runs Home Run Baker ever hit in one year? It was twelve. That was his best year. In 1914 Baker and I tied for the lead with the grand total of eight each. Now, little Albie Pearson will hit that many accidentally. So you see, the game is altogether different from what it was ....

Like I said, those old Baltimore Orioles didn't pay any more attention to Ned Hanlon, their manager, than they did to the batboy. When I came into the league, that whole bunch had moved over to Brooklyn, and Hanlon was managing them there, too. He was a bench manager in civilian clothes. When things would get a little tough in a game, Hanlon would sit there on the bench and wring his hands and start telling some of those old-timers what to do. They'd look at him and say, "For Christ's sake, just keep quiet and leave us alone. We'll win this ball game if you only shut up."

They would win it, too. If there was any way to win, they'd find it. Like Wee Willie Keeler. He was really something. That little guy couldn't have been over five feet four, and he only weighed about 140 pounds. But he played in the Big Leagues for 20 years and had a lifetime batting average of close to .350 .... "Hit 'em where they ain't," he used to say. And could he ever! He choked up on the bat so far he only used about half of it, and then he'd just peck at the ball. Just a little snap swing, and he'd punch the ball over the infield. You couldn't strike him out. He'd always hit the ball somewhere. And could he fly down to first! Willy was really fast .... They would win it, too. If there was any way to win, they'd find it. Like Wee Willie Keeler. He was really something. That little guy couldn't have been over five feet four, and he only weighed about 140 pounds. But he played in the Big Leagues for 20 years and had a lifetime batting average of close to .350 .... "Hit 'em where they ain't," he used to say. And could he ever! He choked up on the bat so far he only used about half of it, and then he'd just peck at the ball. Just a little snap swing, and he'd punch the ball over the infield. You couldn't strike him out. He'd always hit the ball somewhere. And could he fly down to first! Willy was really fast ....You know, there were a lot of little guys in baseball then. McGraw was a fine ballplayer and he couldn't have been over five feet six or seven. And Tommy Leach, with Pittsburgh -- he was only five feet six and he couldn't have weighed over 140. He was a beautiful ballplayer to watch. And Bobby Lowe, who was the first player to ever hit four home runs in one game. He did that in 1894. That was something, with that old dead ball. Bobby and I played together for three or four years in Detroit, around 1905 or so.

Dummy Hoy was even smaller, about five-five. You remember him, don't you? He died in Cincinnati only a few years ago, at the age of ninety-nine. Quite a ballplayer. In my opinion, Dummy Hoy and Tommy Leach should both be in the Hall of Fame.

Do you know how many bases Dummy Hoy stole in his major-league career? Over 600!* That alone should be enough to put him in the Hall of Fame. We played alongside each other in the outfield with the Cincinnati club in 1902. He started in the Big Leagues way back in the 1880's, you know, so he was on his way out then ... but even that late in his career he was a fine out fielder. A great one.

I'd be in right field and he'd be in center, and I'd have to listen real careful to know whether or not he'd take a fly ball. He couldn't hear, you know, so there wasn't any sense in me yelling for it. He couldn't talk either, of course, but he'd make a kind of throaty noise, kind of a little squawk, and when a fly ball came out and I heard this little noise I knew he was going to take it. We never had any trouble about who was to take the ball.

Did you know that he was the one responsible for the umpire giving hand signals for a ball or a strike? Raising his right hand for a strike, you know, and stuff like that. [Dummy Hoy]'d be up at bat and he couldn't hear and he couldn't talk, so he'd look around at the umpire to see what the pitch was, a ball or a strike. That's where the hand signs for the umpires calling balls and strikes began. That's a fact. Very few people know that.

-- Sam Crawford

The Glory of Their Times (Ritter)

* Actually, Hoy is credited with 594 base thefts -- ed.

IMAGE: Willie Keeler

6th INNING

Stats: Record Holders (Pitching, through the 2005 season)

Career Wins:

Cy Young (1890-1911) 511 ... Walter Johnson (1907-27) 417 ... Pete Alexander (1911-30) 373

Wins in a Season (before 1900):

Charley Radbourne (1884) 59 ... John Clarkson (1885) 53 ... Guy Hecker (1884) 52

Wins in a Season (after 1900):

Jack Chesbro (1904) 41 ... Ed Walsh (1908) 40 ... Christy Mathewson (1908) 37

Career ERA:

Ed Walsh (1904-17) 1.82 ... Addie Joss (1902-10) 1.89 ... Mordecai Brown (1903-16) 2.06

Single-Season ERA:

Tim Keefe (1880) .857 ... Dutch Leonard (1914) .961 ... Mordecai Brown (1906) 1.038

Career Saves (through 2005):

Lee Smith (1980-97) 478 ... Trevor Hoffman (1993- ) 436 ... John Franco (1984- ) 424

Saves in a Season:

Bobby Thigpen (1990) 57 ... Eric Gagne (2003) 55 ... John Smoltz (2002) 55

Career Shutouts:

Walter Johnson (1907-27) 110 ... Pete Alexander (1911-30) 90 ... Christy Mathewson (1900-16) 79

Career Complete Games:

Cy Young (1890-1911) 749 ... Pud Galvin (1875-92) 646 ... Tim Keefe (1880-93) 554

Career Losses:

Cy Young (1890-1911) 316 ... Pud Galvin (1875-92) 308 ... Nolan Ryan (1966-93) 292

SO/9IP in a Season: SO/9IP in a Season:Randy Johnson (2001) 13.41 ... Pedro Martinez (1999) 13.20 ... Kerry Wood (1998) 12.58

Strikeouts in a Season:

Matt Kilroy (1886) 513 ... Toad Ramsey (1886) 499 ... Hugh Daily (1884) 483*

Strikeouts to Walks in a Season:

Bret Saberhagen (1994) 11.000 ... Jim Whitney (1884) 10.000 ... Jim Whitney (1883) 9.857

*In modern times Nolan Ryan has the most strikeouts in a season (1973) with 383, followed by Sandy Koufax with 382 in 1965 -- ed.

IMAGE: Randy Johnson

7th INNING

Year in Review: 1906

The year 1906 saw the first one-city World Series. Over the next 83 years there would be 14 more -- 13 played in New York. But the '06 Series was the first, last, and only all-Chicago affair.

In early June, player/manager Frank Chance's Cubs kicked off the greatest NL dynasty of the 1900s by building a big lead over John McGraw's Giants and then coasting to a major league-record 116 wins against only 36 losses.

First baseman Chance led an offense that outscored the nearest team by 80 runs; he tied Honus Wagner for the league lead in both runs with 103 and on-base average at .406. Chance anchored the NL's tightest-fielding infield, made up of .327 hitter and RBI leader Harry Steinfeldt and the immortal double-play combination of Joe Tinker and Johnny Evers. Up-and-coming star Frank "Wildfire" Schulte led the Cubs outfielders with 13 triples and four home runs, and Jimmy Sheckard banged out 27 doubles. Chicago pitchers allowed only 381 runs, 89 fewer than the nearest team, and turned in a 1.76 ERA.

Four of the five Cubs starters -- Three-Finger Brown, Ed Reulbach, Jack Pfiester, and Orvie Overall -- had ERAs below 2.00, and Brown's ERA of 1.04 is the second-lowest in history.

The Cubs finished a mere 20 games ahead of the Giants, who won 96 games. The entire second division -- Brooklyn, Cincinnati, St. Louis, and Boston -- came in 50 or more games off the pace. Among the few offensive categories not dominated by Cubs were batting average, led by Wagner at .339, and slugging average, led by Brooklyn's Harry Lumley at .477.

Chicago's American League counterpart had a more difficult summer, as the White Sox wallowed in fourth place behind Philadelphia, New York, and Cleveland. Then in early August, the Sox reeled off an AL-record 19 straight victories to secure the pennant. Unlike their crosstown rivals, the White Sox did not monopolize the offensive leader board, but their attack -- which produced 570 runs, third-most in the league -- hardly deserved its nickname, the "Hitless Wonders."

Chicago had no sluggers to compare with St. Louis' George Stone, the league leader in batting at .358 and slugging at .501, nor with Cleveland's Elmer Flick, who knocked 33 doubles and a league-high 22 triples. But slugging was not the name of the game in the dead-ball era. Fielder Jones' Sox scratched out their runs by drawing walks (outfielders Jones and Ed Hahn were two and three in the AL in free passes) and working a running game (both second baseman Frank Isbell and first baseman Jiggs Donahue were in the Top Five in stolen bases). Chicago's only big RBI man was shortstop George Davis, who drove in 80 runs, third in the league behind [Nap] Lajoie and Philadelphia slugger Harry Davis.

It was only in pitching where the White Sox could compete with the Cubs. But even with ace Doc White (who won the ERA title at 1.52) and Ed Walsh (the author of a league-leading ten shutouts), the American Leaguers went into the World Series as distinct underdogs...

-- David Nemec, et al.

The Baseball Chronicle

8th INNING

The 1906 World Series

Chicago White Sox (4) v Chicago Cubs (2) Chicago White Sox (4) v Chicago Cubs (2)Played in snowy October weather in Chicago, games one through four were understandably low-scoring. Nick Altrock beat the Cubs 2-1 in the opener, played in the Cubs' West Side Park, and Walsh won game three 3-0. But going into the fifth game, the Series was tied 2-2. Then, suddenly, the Hitless Wonders' bats caught fire, defeating Reulbach 8-6 and banging around both Brown and Overall to win the deciding game 8-3. The White Sox narrowly outhit their opponents .198 to .196, but more than halved the mighty Cubs' ERA, 1.50 to 3.40. (The Baseball Chronicle, David Nemec, et al.)

October 9-14

West Side Grounds (Chicago), Southside Park (Chicago)

Game 1: Chicago AL 2, Chicago NL 1

Game 2: Chicago NL 7, Chicago AL 1

Game 3: Chicago AL 3, Chicago NL 0

Game 4: Chicago NL 1, Chicago AL 0

Game 5: Chicago AL 8, Chicago NL 6

Game 6: Chicago AL 8, Chicago NL 3

CHICAGO WHITE SOX: Nick Altrock (p), George Davis (ss), Jiggs Donahue (1b), Patsy Dougherty (of), Ed Hahn (of), Frank Isbell (2b), Fielder Jones (pf), Ed McFarland (ph), Bill O'Neill (of), Frank Owen (p), George Rohe (3b), Billy Sullivan (c), Lee Tannehill (ss), Babe Towne (ss), Ed Walsh (p), Doc White (p). Mgr: Fielder Jones

CHICAGO CUBS: Mordecai Brown (p), Frank Chance (1b), Johnny Evers (2b), Doc Gessler (ph), Solly Hodfman (of), Johnny Kling (c), Pat Moran (ph), Orval Overall (p), Jack Pfiester (p), Ed Reulbach (p), Frank Schulte (of), Jimmy Sheckard (of), Harry Steinfeldt (3b), Joe Tinker (ss). Mgr: Frank Chance

The Cubs went into the World Series having won 116 games in the regular season, leading the league in hitting and pitching (1.76 combined ERA).

9th INNING

Player Profile: James Creighton Player Profile: James Creighton Born: April 14, 1841 (New York, NY)

Died: October 18, 1862

Played for: Young America Base Ball Club (1857), Niagara Club (1858), Brooklyn Excelsiors (1859-62)

[Baseball's] first real superstar was pitcher James Creighton, who started his career at the age of 17 and went on to national renown with the Brooklyn Excelsiors. In an 1863 Peck & Snyder trade card, Creighton is portrayed throwing a ball underhand, as the rules required at the time. The rules also required pitchers to toss the ball gently over the plate without snapping their wrist during delivery. But Creighton managed to snap his wrist without being detected, generating speed on the ball "as swift as [if] sent from a cannon." He bewildered most of his opposing batsmen, who stood only 45 feet from the pitcher's box -- another rule at the time.

During a barnstorming tour with the Excelsiors in 1860, Creighton proved to be the game's first big draw. Fans in upstate New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Delaware came out in droves to see him pitch. Creighton's dominance continued into the following year at the Grand Match, the first baseball match game to be played for a trophy. On November 21, 1861, at the Elysian Fields, an "all-star" team from Brooklyn took on an all-star team from New York. Creighton pitched Brooklyn to an 18-6 win. The lemon peel-style baseball used in this game ... by the game's first star ... [is] a glorious relic. Tragically, Creighton's reign was cut short the following year, when he died from a ruptured bladder after hitting a home run against the Unions of Morrisania. His stature was so widespread by then that the president of the Excelsiors, concerned that American mothers would deem baseball too dangerous for their sons, told reporters that the accident had happened while Creighton was playing cricket, not baseball.

-- Stephen Wong

Smithsonian Baseball

EXTRA INNINGS

They Played the Game

Larry Doby

(1947-59)

The first African-American to play in the American League, Doby is a Hall-of-Famer who won home run titles in 1953 and 1955. He played for the Cleveland Indians during their pennant-winning seasons of 1948 and 1954. Before his time in the AL, Doby played four years with the Newark Eagles of the Negro National League. He and Don Newcombe became the first former major leaguers to play for a Japanese team (Chunichi Dragons, 1962).

BORN: 12.13.23 (Camden, SC) .283, 253, 970

All-Star 1949-55

Hall of Fame (1998)

Tony Perez

(1964-86)

Perez had a reputation as a clutch hitter who drove in 90 or more runs in eleven consecutive seasons (1967-77) and 100 or more in seven seasons. After being an integral part of Cincinnati's "Big Red Machine" and playing in three World Series (1970, 1972, 1975), Perez moved on to the Montreal Expos, Boston Red Sox and Philadelphia Phillies. He managed the Cincinnati Reds in 1993 and the Florida Marlins in 2001.

BORN: 5.14.42 (Ciego de Avila, Cuba) .279, 379, 1652

All-Star 1967-70, 1974-76 1967 ML AS MVP

Hall of Fame (2000)

Frank Baker

(1908-22)

Third baseman "Home Run" Baker was the top power hitter of his day who led the American League in RBI in 1912 and 1913 and leading in home runs between 1911 and 1914. He earned his nickname by hitting long balls off Christy Mathewson and Rube Marquard in the 1911 World Series. He played for the Philadelphia Athletics (1908-14) and the New York Yankees (1916-18, 1921-22).

"Home Run" BORN: 3.13.1886 (Trappe, MD)

Hall of Fame (1955)

Ted Simmons

(1968-88)

One of the best hitting catchers in major league history, the switch-hitting Simmons clubbed over 20 homers in six seasons and collected over 90 RBIs eight times. He played for the St. Louis Cardinals (1968-80), Milwaukee Brewers (1981-85) and Atlanta Braves (1968-88).

BORN: 9.9.49 (Highland Park, MI) .285, 248, 1389

All-Star 1972-74, 1977-79, 1981, 1983 Silver Slugger 1980

Billy Hamilton

(1888-1901)

The 5'6" Hamilton was one of the greatest leadoff hitters in baseball history. He led the league in runs, walks, on-base percentage and stolen bases in 1894, and also set the all-time ML record for runs scored in a single season (192). His 115 base thefts in 1891 stood as an NL record for over 80 years. Hamilton hit over .300 for twelve consecutive seasons and is one of only three players whose hits (1,691) exceed games played (1,578). His teams: Kansas City Cowboys (1888-89), Philadelphia Phillies (1890-95), and the Boston Beaneaters (1896-1901).

"Sliding Billy" BORN: 2.16.1866 (Newark, NJ)

Hall of Fame (1961)

THIS MATERIAL IS REPRODUCED FOR NON-PROFIT EDUCATIONAL AND SCHOLARLY PURPOSES ONLY, WHICH COMPLIES WITH THE DOCTRINE OF FAIR USE AS EXPRESSED IN THE COPYRIGHT ACT OF 19 OCTOBER 1976, EFFECTIVE 1 JANUARY 1978 (TITLE 17 OF THE UNITED STATES CODE, PUBLIC LAW 94-553, 90 STAT. 2541.)

|