9 Innings 9 InningsA Baseball History Reader

J. Manning, Editor

|

Issue # 18: December 12, 2006

The Last .400 Hitter ... Ballplayers vs. Fans ... Men in Blue: The Umpires ... The Art of Sliding ... Diamond Disasters ... Stats: Stolen Bases (Career) ... Year in Review: 1917 ... The 1917 World Series ... Player Profile: Luis Aparicio ... Baseball Dictionary (banjo hitter - baseball rule)

|

"Baseball is a lot like life. The line drives are caught, the squibbers go for base hits. It's an unfair game."

-- Ron Kanehl

1st INNING

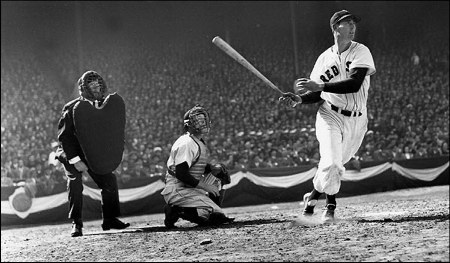

The Last .400 Hitter

[1941] Williams was hot again. Amazingly strong at the plate. He walked frequently -- it was a rare day when he did not receive at least one base on balls -- and frequently he had only one or two official at-bats. Yet he had a hit in practically every game .... Throughout August he stayed close to .410 .... When he had a rare hitless day his average would drop several points, and then he would force it back up again. On August 18 he was down to .405, but in his next three games he had seven hits in twelve at-bats, including five home runs, to lift it to .412, and he was still hitting .410 half a dozen days into September.

Except in Boston, where even his teammates were rooting for him ("He's become positively popular with the other players this year," wrote one newspaperman with obvious surprise), his .400-plus average had not generated a great deal of attention. Attendance in the American League dropped off sharply after the Yankees tore the pennant race apart and DiMaggio stopped hitting .... Didn't Williams' .400 average excite people? Not that much -- at least not until very late in the season .... [P]eople who were then in their late twenties clearly remembered the spate of .400 averages in the early 1920s, seven of them in six seasons. Bill Terry of the Giants had hit .401 in 1930, only a decade earlier ....

So Williams' .410 average in early September was splendid but not earthshaking. What was earthshaking ... was the way he was hitting. He wasn't choking up on the bat and poking safe little singles. He was swinging hard, smashing out doubles, home runs, line drives, long fly balls. He had been well behind in the home-run race earlier in the year, but he hit so many late-season dingers that he moved past the Yankees' Charlie Keller into the league lead.

And he was getting few good pitches to hit. Everybody was walking him. He was given 145 bases on balls that year, almost seventy more than DiMaggio. Slowly the scope of his achievement .. began to be appreciated .... In New York a week into September he wowed a Yankee Stadium crowd by hitting two doubles and a single to lift his average to .413. The Yankee fans even jeered their old favorite, Lefty Gomez, when he walked Ted.

....There were only fifteen games left in the season, but maintaining the blistering pace was becoming increasingly difficult. For a man as sensitive to press coverage and fan comments as Williams was, the pressure must have been excruciating. .... He was in the newspapers every day, and in Boston the press coverage was smothering; there were headlines about him, photographs, cartoons, news stories, features, columns, sidebars, special boxes of statistics on what he had done so far and what he had to do to hit .400.

He went hitless in two successive games (in only four official at-bats) and his average dropped four points to .409. It hovered there for a few more days before another hitless game dropped him to .405, with little more than a week to go. The Red Sox played their last home games of the season on Saturday and Sunday, September 20 and 21, and Williams had three hits in seven at-bats, including his thirty-sixth homer of the year. That splurge lifted his average only a point to .406.

The Red Sox had three games in Washington during the last week of the season and three in Philadelphia. Williams had one hit on the first day in Washington to keep his average at .405 (or precisely .4051, compared to the .4055 it had been the day before; people were beginning to use four decimal points when they discussed Williams' hitting.) But the next day in a doubleheader against the Senators he stumbled badly, getting only one hit in seven at-bats -- and that one an infield single that he barely beat out. One hit in seven at-bats, and his average plummeted all the way down to .401. He had batted only .270 since September 10, and his average had fallen twelve points.

....People began to say that Williams ought to sit out the final three games and not play in Philly. That way he could end the season hitting .401. Joe Cronin, the Red Sox manager, toyed with the idea and mentioned it to Williams, but Williams insisted on playing ....

In Philadelphia on Friday, an off day, Williams went to Shibe Park with a coach and a catcher and took some extra batting practice .... "Hitting here this time of year is a headache," Williams said. "The shadows are bad. You don't get a good look at the ball. But I'm not alibing .... I want to hit over .400, but I'm going to play all three games here even if I don't hit a ball out of the infield. The record's no good unless it's made in all the games."

On Saturday Williams had only one hit in four at-bats and his average fell to .39955. Baseball's long-standing practice was -- and is -- to round off batting averages to the nearest three numbers .... [But if] Ted hadn't played on Sunday his batting average might have been listed in the record books as .400, but no matter how you rounded off the .39955 figure would have echoed and reechoed through baseball history.

....Williams didn't appear confident before the doubleheader on the last day of the season. About all he would say was "I hope I can hit .400" before turning the conversation to a postseason barnstorming trip he and Jimmie Foxx were going on.

Then the first game started. Williams, who was batting fourth, came up for the first time in the second inning. Batting against Dick Fowler ... he took ball one and ball two and then rammed a ground single through the right side of the infield. That lifted his average back over .400 to .401.

He came to bat for the second time in the fifth inning. Fowler missed with his first pitch but came in with the second, and Williams hit it 440 feet over the right-field fence for a long home run. His average was now .402.

The game had become a free-hitting affair, and he batted again the next inning. With the count two balls and no strikes, batting now against a lefthander named Porter Vaughan, he hit another grounder through the hole into right field for his third straight hit.

That raised his average to .404 and practically guaranteed he would finish over .400. He'd have to go hitless in his next five times at bat for his average to fall below that mark. Everyone seemed aware of that and the Red Sox players in the dugout were cheering as vigorously as the crowd was. "His teammates don't consider him a necessary evil anymore," wrote a Boston sportswriter.

Williams came up again in the seventh inning. This time he cracked a line-drive single over the first baseman's head for his fourth straight hit .... For all the hitting (the Red Sox had sixteen hits, the Athletics fifteen) the game was over in two hours and two minutes. The second game, called after the eighth inning because of the darkness in "the crater that was Shibe Park," as someone described the Philadelphia ballpark, took only an hour and thirty one minutes to play. Williams batted three times. He hit yet another ground-ball single to right in his first at-bat, but in his second time up, facing a rookie righthander named Fred Caligiuri, he hit a tremendous shot on a line to right-center field that hit the loudspeaker horns of the public-address system under the 460-foot sign. One writer said it was the hardest Williams had hit a ball in his three seasons with the Red Sox. The ball punched a clean hole in one of the speaker horns, fell back onto the playing field, and Williams was held to a double.

It was the seventh straight time he'd been on base in the doubleheader. He had one more at-bat and for the first time all day he made out, hitting a fly ball to left field. He had had six hits in his eight at-bats and lifted his average six points on the last day of the season to .406 (or, to be precise, .4057.)

.... Someone mentioned the Most Valuable Player award to Williams, and the youngster's face grew serious. "Do you think there's a chance I could win it?" he asked. Then, as though dismissing the idea (DiMaggio eventually won it), he smiled again and said, "Even if I don't, I'll be satisfied with this. What a thrill! I wasn't saying much about it before the game, but I never wanted anything harder in my life."

--Robert W. Creamer

Baseball in '41

2nd INNING

Ballplayers vs. Fans

In no "sport," wrote the editor of Sporting News, is "vicious and vile objurgation" of a performer permitted as in baseball. Jibes like "You bum, you're all in" and "You're a has-been, you ought to be shining shoes or sweeping the streets" were mild compared with the profanities and obscenities frequently directed at players. A bank executive, complaining of these conditions, said that he would attend many more games if he did not have to listen to the epithets hurled at players. A traveling man who said he found conditions the same in all the ball parks objected particularly to such language being used in the presence of ladies. Jack Fournier threatened to quit baseball because of the harassment of Brooklyn fans who persisted in vilifying him with "ugly epithets." His wife had already stopped attending the games because she could not stand the language directed at him.

Every so often an angry player climbed into the stands and attacked a heckler. Rube Waddell beat up one in 1903 .... Sherwood Magee knocked out a drunk who, after abusing him from the bleachers, followed him to the clubhouse to continue his insults. Once Nashville police escorted Detroit manager Ed Barrow to jail for throwing a bucket of water over jeering fans during an exhibition game.

More serious repercussions resulted early in 1912 when Ty Cobb leaped into the stands in Hilltop Park, New York, and assaulted a spectator who had been heckling him. The umpires put Cobb out of the game, and Ban Johnson suspended him indefinitely, pending an investigation. The depth of player resentment of spectator abuse is indicated by the fact that, despite Cobb's unpopularity among them, all eighteen players on the Detroit team opposed Johnson's action .... [T]he players wired Johnson that they would not play another game unless he reinstated Cobb. "If players cannot have protection," they stated, "we must protect outselves." Johnson rejected their demands, declaring they had no business taking the law into their own hands and that a player had only to appeal to the umpire in order to have ruffians ejected from the park. Consequently, the Detroit players carried out a sympathy strike by refusing to play the next day in Philadelphia.

In order to avoid the $5000 penalty to which a club was liable under league rules for failure to play a scheduled game, the Detroit management hastily recruited a makeshift team of strikebreakers, made up of college players and the Detroit coaches, and sent them against the Athletics, who, as might be expected, drubbed them 24-2. Ban Johnson rushed to Philadelphia. The next scheduled game was called off, but Johnson threatened to expel any player who failed to report for the one following. Cobb, who had given out a bitter blast against Ban Johnson, now urged the players to forego the strike and return to work. This they did. Johnson imposed a $50 fine and ten-day suspension on Cobb and $100 fines on each of the other players. Although the strike was quickly broken, it was significant in that it exemplified a growing dissatisfaction among major-league players.

The fine line between the fan's right to jeer as well as cheer and abusive personal vilification was not always distinguishable .... At times players could be at fault, too, by adopting a chip-on-the-shoulder attitude toward fans. Jimmy Archer once attacked a man he thought was flirting with his wife in the stands. Another time Carl Mays accused a spectator of pounding on the dugout, and when the man denied it and called him down, Mays hit him in the head with a baseball. The fan had a warrant sworn out, but the incident was settled when Mays indicated his willingness to apologize ....

Even a hero of Christy Mathewson's stature once overstepped the bounds in his relations with fans. The incident occurred at Philadelphia in 1905. It started with a fight between a New York and a Philly player. Others joined in, and during the fracas Mathewson punched a lemonade boy passing in front of the Giants' bench, supposedly for making a remark about a New York player. This "brutal blow," as a Philadelphia writer called it ... split the boy's lip and loosened some of his teeth. After the game several thousand people mobbed the Giants in their carriages and pelted them with stones and other missiles before the police could quell the mob.

This episode was not in keeping with the accepted stereotype of Mathewson .... Unlike Cobb, Mathewson was a hero who could be loved, and in those days if a boy with visions of becoming a pitcher were asked which player he would like to emulate, the chances were better than even that he would choose Christy Mathewson. He became such a symbol of clean living and sportsmanship that he was invited to address juvenile delinquents and boys' organizations .... In fact, so lauded were his virtues that there was danger of his being considered a prig, so assurances were given that he was also human enough to take a drink, play poker, and even utter an oath on occasion.

-- Harold Seymour

Baseball: The Golden Age

3rd INNING

Men in Blue: The Umpires

In 1914, Christy Mathewson, the pitcher, said, "many fans look upon umpires as a sort of necessary evil to the luxury of baseball, like the odor that follows an automobile." Such fans should imagine what life would be like without the likes of Richie Garcia and Durwood Merrill, two of the American league's finest. In 1914, Christy Mathewson, the pitcher, said, "many fans look upon umpires as a sort of necessary evil to the luxury of baseball, like the odor that follows an automobile." Such fans should imagine what life would be like without the likes of Richie Garcia and Durwood Merrill, two of the American league's finest.Umpires' compensation and benefits have markedly improved in recent years. In 1998 [sic], the first-year umpire earns a base salary of $75,000 a year. An umpire in his thirtieth season earns $225,000. Every November 1 every umpire gets a $20,000 annual bonus, paid from baseball's pot of postseason revenues. Umpires get $5,000 for working the All-Star Game, $12,500 for a Division Series, $15,000 for a League Championship Series and $17,500 for the World Series. In addition, each of the fifteen crew chiefs (eight in the American League, seven in the National) get an extra $7,500 a year. All umpires get thirty-one vacation days during the season -- one week early in the season, two weeks between Memorial Day and Labor Day, one week in September, plus three additional days somewhere along the line, and the All-Star break. That is not a lot of time off, considering that for umpires there are no home games.

A senior umpire who does a lot of postseason work can earn maybe half as much as a mediocre uitlity infielder. The infielder's mediocrity is apparent. Umpires aspire to unnoticed excellence.

It is said that umpires are expected to be perfect on opening day and improve all season.

Garcia, forty-four, came to umpiring from Key West and the Marine Corps. The corps was good training for a vocation that an umpire once summarized in seven words: "Call 'em fast and walk away tough." Garcia is a compact man with a spring in his step and baseball on his brain. On off-days, he watches televised baseball games.

Like the best baseball people, if he is awake he is working. He studies box scores to be aware of what hitters are hot, what pitchers are wild, what fielders are making errors. The night before working home plate, he begins thinking about tomorrow's starting pitchers: their moves to first, their tendency to balk, their mix of pitches.

Merrill, forty-seven, a bear of a man from Oklahoma, via Hooks, Texas, was a burned-out high-school football coach at twenty-eight, so he became an umpire. Studies show that umpires endure stress levels not much lower than those of air-traffic controllers, big-city policemen, inner-city teachers, and Texas high-school football coaches ....

The key to excellence, saysMerrill, is "angle and position": being in the best position to make the difficult calls such as swipe tags and trapped balls. There is another ingredient: confidence.

When Babe Ruth was called out on strikes by umpire Babe Pinelli, Ruth made a populist argument, inferring weight from raw numbers: "There's forty thousand people here who know that last one was a ball, tomato head!" Pinelli replied with the assurance of John Marshall: "Maybe so, but mine is the only opinion that counts" ....

Umpires are islands of exemption from the litigiousness of American life. As has been said, if someone gets three strikes on you, the best lawyer can't get you off.

...."Anybody can see high and low," says Merrill. "It is 'in and out' that is umpiring." The saying "Good umpires are pitchers' umpires" means that good umpires are not afraid to call strikes. Their calling borderline pitches strikes makes pitchers more confident and batters more aggressive. That is, good umpiring makes good baseball, a fact from which a large lesson flows.

The business of umpiring is to regulate striving, to turn it from chaos into ordered competition, thereby enabling excellence to prevail over cruder qualities ....

-- George F. Wills

March 29, 1987

Bunts

4th INNING

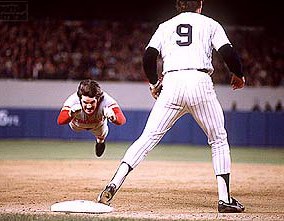

The Art of Sliding

The ball and runner are streaking toward third base from different directions and will arrive at virtually the same instant. The third baseman braces himself for the collision and concentrates intensely on catching the ball and slapping down his glove. The runner leaves his feet and swoops down into the dirt to evade the tag, knock the ball loose, or simply kick up a swirl of dust to obscure the umpire's view. The slide can be baseball's most exciting moment. The ball and runner are streaking toward third base from different directions and will arrive at virtually the same instant. The third baseman braces himself for the collision and concentrates intensely on catching the ball and slapping down his glove. The runner leaves his feet and swoops down into the dirt to evade the tag, knock the ball loose, or simply kick up a swirl of dust to obscure the umpire's view. The slide can be baseball's most exciting moment.The hook slide is used if the runner needs to elude a tag on a throw that has beaten him to the base. The runner rolls his upper body out of the way and hooks the bag with a toe, leaving very little to tag.

Takeout slide: When forced out at second, the runner at first is instructed to upend the second baseman or shortstop in order to ruin ("break up") the double play. Usually he will aim for the infielder's legs to disrupt the throw.

[The] Figure-4 slide or "bent leg slide" is the simplest and safest slide. The runner tucks one leg under the other to form a number 4 shape. His hands should be back out of harm's way, his head up watching the base, which he touches with his straight leg. The Figure-4 can be turned into a "pop-up" slide, in which the runner uses the base as a brace and pops immediately to a standing position so he can advance to the next base.

Headfirst slides have become popular thanks to aggressive runners like Pete Rose and Rickey Henderson. The runner dives horizonal and low, with his palms down and fingers up. The hands touch the ground and the base first. Headfirst slides get you there faster, and are safer now that helmets and batting gloves have become standard equipment. But even with protection, very few players attempt to slide into home headfirst, where a well-protected catcher is likely to be waiting.

Mike King Kelly, hero of the Chicago White Stockings in the 1880s, popularized the hook slide. Kelly swiped 84 bases in 1887, and was so famous in his time that he became the subject of a hit song: "Your running's a disgrace / Stay there, hold your base! / If someone doesn't steal you / and your batting doesn't fail you / they'll take you to Australia! / Slide, Kelly, Slide!" Kelly's final words, while falling off a stretcher after catching pneumonia, were, "This is my last slide."

-- Dan Gutman

The Way Baseball Work

5th INNING

Diamond Disasters

[Sept. 16, 1975] It was the most appalling shutout slaughter of the twentieth century. Before they had even managed to get three outs, the [Chicago] Cubs were praying for rain and looking for a hole to hide in at Wrigley Field. The fans had hardly settled in their seats before starter Rick Reuschel was on his way to the showers after giving up eight runs, six hits, and two walks in only 1/3 inning. The Pirates added another tally in the first and went on to batter Cubs pitching for 24 hits. Every single Pirate in the starting lineup collected at least one hit and scored at least one run. After the first inning, the vendors were selling hot dogs to go. Nobody was more bored by this trouncing than some of the Cubs themselves, especially outfielder Jose Cardenal. He spent most of the time -- when not chasing down Pirate extra-base hits -- studying the ivy on the outfield wall. "I was watching a spider crawl through the ivy," he said. "What else was there to do out there in a game like that?"

Pittsburgh Pirates 22, Chicago Cubs 0

[June 18, 1953] There were no limits to the mortification the Tigers were willing to inflict upon themselves. After getting blown out by the Red Sox 17-1 the day before, the Tigers were bombed by Boston for another 17 runs -- only this time in one inning .... Detroit trailed Boston 5-3 going into the bottom of the seventh inning when the barrage started. The carnage lasted 48 minutes and when the toothless Tigers finally staggered off the field, they carried with them the shameful record of allowing the highest-scoring inning in modern history. In the inning, three Detroit pitchers combined to face 23 batters before getting three outs. They surrendered 11 singles, two doubles, a home run and six walks. They had no one to blame but themselves. All runs were earned.

Boston Red Sox 23, Detroit Tigers 3

-- Bruce Nash & Allan Zullo

The Baseball Hall of Shame

6th INNING

Stats: Stolen Bases (Career)

1. Rickey Henderson 1,186 ... 2. Lou Brock 938 ... 3. Billy Hamilton 912 ... 4. Ty Cobb 892 ... 5. Time Raines 787 ... 6. Vince Coleman 752 ... 7. Eddie Collins 744 ... 8. Arlie Latham 739 ... 9. Max Carey 738 ... 10. Honus Wagner 722 ... 11. Joe Morgan 689 ... 12. Willie Wilson 668 ... 13. Tom Brown 657 ... 14. Bert Campaneris 649 ... 15. George Davis 616 ... 16. Dummy Hoy 594 ... 17. Maury Wills 586 ... 18. George Van Haltren 583 ... 19. Ozzie Smith 580 ... 20. Hugh Duffy 574 ... 21. Bid McPhee 568 ... 22. Davey Lopes 557 ... 23. Cesar Cedeno 550 ... 24. Bill Dahlen 547 ... 25. Brett Butler 543 ... 26. John Ward 540 ... 27. Herman Long 534 ... 28. Patsy Donovan 518 ... 29. Jack Doyle 516 ... 30. Harry Stovey 509 ... 31. Fred Clarke 506 ... 32. Luis Aparicio 506 ... 33. Otis Nixon 498 ... 34. Willie Keeler 495 ... 35. Clyde Milan 495 ... 36. Omar Moreno 487 ... 37. Paul Molitor 484 ... 38. Mike Griffin 473 ... 39. Tommy McCarthy 468 ... 40. Jimmy Sheckard 465 ... 41. Bobby Bonds 461 ... 42. Ed Delahanty 455 ... 43. Ron LeFlore 455 ... 44. Curt Welch 453 ... 45. Steve Sax 444 ... 46. Joe Kelley 443 ... 47. Sherry Magee 441 ... 48. John McGraw 436 ... 49. Tris Speaker 432 ... 50. Bob Bescher 428 1. Rickey Henderson 1,186 ... 2. Lou Brock 938 ... 3. Billy Hamilton 912 ... 4. Ty Cobb 892 ... 5. Time Raines 787 ... 6. Vince Coleman 752 ... 7. Eddie Collins 744 ... 8. Arlie Latham 739 ... 9. Max Carey 738 ... 10. Honus Wagner 722 ... 11. Joe Morgan 689 ... 12. Willie Wilson 668 ... 13. Tom Brown 657 ... 14. Bert Campaneris 649 ... 15. George Davis 616 ... 16. Dummy Hoy 594 ... 17. Maury Wills 586 ... 18. George Van Haltren 583 ... 19. Ozzie Smith 580 ... 20. Hugh Duffy 574 ... 21. Bid McPhee 568 ... 22. Davey Lopes 557 ... 23. Cesar Cedeno 550 ... 24. Bill Dahlen 547 ... 25. Brett Butler 543 ... 26. John Ward 540 ... 27. Herman Long 534 ... 28. Patsy Donovan 518 ... 29. Jack Doyle 516 ... 30. Harry Stovey 509 ... 31. Fred Clarke 506 ... 32. Luis Aparicio 506 ... 33. Otis Nixon 498 ... 34. Willie Keeler 495 ... 35. Clyde Milan 495 ... 36. Omar Moreno 487 ... 37. Paul Molitor 484 ... 38. Mike Griffin 473 ... 39. Tommy McCarthy 468 ... 40. Jimmy Sheckard 465 ... 41. Bobby Bonds 461 ... 42. Ed Delahanty 455 ... 43. Ron LeFlore 455 ... 44. Curt Welch 453 ... 45. Steve Sax 444 ... 46. Joe Kelley 443 ... 47. Sherry Magee 441 ... 48. John McGraw 436 ... 49. Tris Speaker 432 ... 50. Bob Bescher 4287th INNING

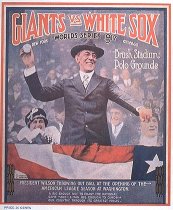

Year in Review: 1917

Very quietly, the Chicago White Sox rebuilt during the mid-1910s. Taking advantage of the troubled financial times during World War I, Sox owner Charlie Comiskey bought and traded for many of the game's top performers until he pieced together one of the dead-ball era's finest teams./ In 1917, Comiskey's White Sox became the last team during the 1910s to win 100 games and left defending champion Boston nine lengths in arrears.

John McGraw's Giants, winners by a slightly wider margin of 10 games in the NL, got most of the ink in 1917 and embarked on their fifth World Series since 1905 as solid favorites. It was during the second week in October 1917 that the rest of the nation awoke to Chicago's secret. The White Sox not only had pitching and defense as was their custom, but now they also could hit and score. Moreover, they were smarter and better trained in fundamentals than the Giants.

All of that began to come clear in Game 5 at Chicago. The two teams had previously traded pairs of victories, each winning twice in its home park, and in the fifth contest the Giants looked ready to take command when they bolted to a 5-2 lead heading into the bottom of the seventh. Then the roof fell in on New York. The White Sox belted Slim Sallee for three runs and continued the onslaught into the next inning against Pol Perritt, finally winning 8-5....

Two days later, in New York, [Red] Faber got his third start against Rube Benton, who had blanked Chicago 2-0 in Game 3. Benton continued his mastery against the Sox -- he concluded the series with a perfect 0.00 ERA -- but was undone by his teammate's inability to execute basic plays. In the third inning, Eddie Collins reached on a bad throw and Joe Jackson on a dropped fly. Happy Felsch then got aboard on a fielder's choice as Giants third baseman Heinie Zimmerman chased Collins across the plate in a botched rundown that earned Zimmerman goat's horns, though the fault was not really his. When all three runners -- Collins, Jackson, and Felsch -- eventually scored, the AL had its seventh fall classic triumph in the past eight seasons.

Season Highlights

-- David Nemec & Saul Wisnia

Baseball: More Than 150 Years

NL: New York, 98-56 ... Philadelphia, 87-65 ... St. Louis, 82-70 ... Cincinnati, 78-76 ... Chicago, 74-80 ... Boston, 72-81 ... Brooklyn, 70-81 ... Pittsburgh, 561-103

AL: Chicago, 100-54 ... Boston, 90-62 ... Cleveland, 88-66 ... Detroit, 78-75 ... Washington, 74-79 ... New York, 71-82 ... St. Louis, 57-97 ... Philadelphia, 55-98

8th INNING

The 1917 World Series The 1917 World SeriesChicago White Sox (4) v New York Giants (2)

October 6-15

Comiskey Park (Chicago), Polo Grounds (New York)

Game 1: Chicago 2, New York 1

Game 2: Chicago 7, New York 2

Game 3: New York 2, Chicago 0

Game 4: New York 5, Chicago 0

Game 5: Chicago 8, New York 5

Game 6: Chicago 4, New York 2

CHICAGO: Eddie Cicotte (p), Eddie Collins (2b), Shano Collins (of), Dave Danforth (p), Red Faber (p), Happy Felsch (of), Chick Gandil (1b), Joe Jackson (of), Nemo Leibold (of), Byrd Lynn (ph), Fred McMullin (3b), Swede Risberg (ph), Reb Russell (p), Ray Schalk (c), Buck Weaver (ss), Lefty Williams (p). Mgr: Pants Rowland

NEW YORK: Fred Anderson (p), Rube Benton (p), George Burns (of), Art Fletcher (ss), Buck Herzog (2b), Walter Holke (1b), Benny Kauff (of), Lew McCarty (c), Pol Perritt (p), Bill Rariden (c), Dave Robertson (of), Slim Sallee (p), Ferdie Schupp (p), Jeff Tesreau (p), Jim Thorpe (of), Joe Wilhoit (ph), Heinie Zimmerman (3b). Mgr: John McGraw

Jim Thorpe, the noted All-American athlete, made his only World Series appearance in Game 5, playing in the outfield for the Giants. Lefty Dave Robertson took his place at the plate, however.

9th INNING

Player Profile: Luis Aparicio Player Profile: Luis AparicioNickname: "Little Louie"

Born: April 29, 1934 (Maracaibo, Venezuela)

ML Debut: April 17, 1956

Final Game: September 28, 1973

Bats: Right Throws: Right

5' 9" 160

Hall of Fame: 1984 (Baseball Writers, 341 votes on 403 ballots, 84.62%)

Baseball was a tradition in the Aparicio family. Luis Aparicio, Sr. was considered one Venezuela's greatest shortstop and, with brother Ernesto, owned a winter league. Luis Aparicio, Jr. signed with the Chicago White Sox for $10,000 in 1955. Starting in place of another Venezuelan shortstop, Chico Carrasquel, in his rookie year, Aparicio led the American League in stolen bases (21) and was named the AL and Sporting News Rookie of the Year. For nine years in a row (1956-1964) Aparicio was the AL's top base stealer, collecting 57 in 1964. He won the Gold Glove nine times and was a ten-time All-Star. For eight consecutive seasons (1959-1966), Aparicio led all AL shortstops in fielding percentage. He teamed with second baseman Nellie Fox for many defensive gems; the pair also provided Chicago with a potent one-two punch at the top of the batting order. According to Fox: "What is the top requirement for a second baseman? A fine shortstop. I'm fortunate in having the greatest shortstop in baseball -- Luis Aparicio." Aparicio was a key part of the 1959 "Go-Go" White Sox who won the AL pennant that year. In 1963 he was traded to Baltimore, and four years later helped the Orioles reach the World Series, where they swept the Los Angeles Dodgers. Back with the Chisox in 1968, Aparicio had his best offensive season in 1970, batting .313 and scoring 86 runs. He closed out his career with three seasons as a Boston Red Sox. In 18 seasons he never played an inning at a position other than shortstop. When he retired, Aparicio was the all-time leader in games played (2,581), assists (8,016), and double plays by a Major League shortstop. He also held the AL record for putouts (4,548), and had 506 career stolen bases. Luis Aparicio, Jr. was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1984.

-- J. Manning

"That little guy is just about the greatest shortstop I've ever seen. I can't imagine how anybody could possibly be any better, no matter how far back you go."

-- Ralph Houk

"I watched Luis Aparicio play in Caracas from the time he was a young boy. His father was one of the greatest shortstops to play in Venezuela. He was called 'Luis le Grande.' As Luis got older and played professional ball I saw that he had the talent to play in the major leagues. I was responsible for the White Sox signing him. In 1954 I called Frank Lane from Caracas and told him about Aparicio. Lane said I should bring him to the States. He was assigned to Waterloo, in Class A, and then Memphis. In 1956 he was ready to play in the big leagues. So I got traded to Cleveland to make room for him. I was happy to help him. And he was always grateful and told sportswriters about me. When I was on Cleveland I talked to him almost every day. On my first trip back to Chicago, Luis was waiting for me. He told me, 'I want to go home.' 'Why?' 'Because Income Tax took all my money.' 'Speak to the White Sox. I know they're going to help you.' 'No, no, no. I want to go home tomorrow.' 'Luis, you can't go home. You've proved to everybody that you can play in the big leagues. And it's because of you I now play in Cleveland. So you better stay here.' That's when Aparicio started to collect his salary without being taxed. The White Sox paid his tax in order to keep him in America."

-- Chico Carrasquel

We Played the Game

EXTRA INNINGS

Baseball Dictionary

banjo hitter

A batter who cannot hit the long ball. Some banjo hitters, like Bert Campaneris, were nonetheless very effective in getting on base.

baptism

Using rubbing mud to remove the sheen from a new baseball before it is put into play. Usually performed by the home plate umpire.

barber

(1) A talkative player. (2) A pitcher who throws close to a batter's head. (3) A pitcher with such pinpoint control that he can "shave" the edge of the strike zone.

barn ball

A forerunner of baseball that survived after baseball was created. It was a game of two players, a ball, a bat (usually an ax handle or stick), and the side of a barn or other building. One player threw the ball against the barn for the other to hit with the bat. If the batter missed and the pitcher caught it, the batter was out and the pitcher was up. However, if the batter hit the ball he had a chance to score a run if he could touch the barn and return to his batting position before the pitcher could retrieve the ball and hit the batter with it -- Dickson Baseball Dictionary.

Baseball Annie

A baseball groupie; an unattached woman who follows ballplayers around.

baseball arm

A sore arm caused by playing baseball. Also, baseball finger, caused by damage to the tendon at the fingertip caused by the repeated impact of a ball. Also, baseball pitcher's elbow, the fracture of bone or cartilage from the head of the radius at the elbow due to strenuous pitching; also, baseball shoulder, caused by the buildup of calcific deposits and fraying of tendons in a player's shoulder.

Baseball Assistance Team

An organization that raises money for indigent ballplayers.

Baseball Chapel

Based in Bloomingdale, NJ, this organization of major and minor league players seeks to spread the Christian gospel to other ballplayers throughout North America.

Baseball Player of the Year

Originally, an annual award presented by Seagram's Distillers and based on fan voting. Since 1988 it's been given by the Associated Press, and is based on the voting of sportswriters and broadcasters.

baseball rule

A legal construct that protects teams from lawsuits brought by spectators who have been injured by flying bats, baseballs, etc.

THIS MATERIAL IS REPRODUCED FOR NON-PROFIT EDUCATIONAL AND SCHOLARLY PURPOSES ONLY, WHICH COMPLIES WITH THE DOCTRINE OF FAIR USE AS EXPRESSED IN THE COPYRIGHT ACT OF 19 OCTOBER 1976, EFFECTIVE 1 JANUARY 1978 (TITLE 17 OF THE UNITED STATES CODE, PUBLIC LAW 94-553, 90 STAT. 2541.)

|