9 Innings 9 InningsA Baseball History Reader

J. Manning, Editor

|

Issue # 13: November 7, 2006

Breaking Baseball's Color Barrier ... The First Truly Exciting All-Star Game ... The Hot Stove ... The Man With No Strike Zone ... What the Black Sox Did for Baseball ... Stats: Hits ... Year in Review: 1912 ... The 1912 World Series ... Player Profile: Duke Snider ... They Played the Game

|

"No game in the world is as tidy and dramatically neat as baseball, with cause and effect, crime and punishment, motive and result, so cleanly defined."

-- Paul Gallico

1st INNING

Breaking Baseball's Color Barrier

Baseball hadn't always been segregated. Right after the Civil War, during baseball's infancy, blacks played alongside whites. Two brothers, Moses Fleetwood "Fleet" Walker and Welday Wilberforce Walker, both played for Toledo in the American Association, and Fleet Walker and black pitching star George Stovey played for Newark in the 1880s when more than twenty blacks held positions in various leagues around the country. Baseball hadn't always been segregated. Right after the Civil War, during baseball's infancy, blacks played alongside whites. Two brothers, Moses Fleetwood "Fleet" Walker and Welday Wilberforce Walker, both played for Toledo in the American Association, and Fleet Walker and black pitching star George Stovey played for Newark in the 1880s when more than twenty blacks held positions in various leagues around the country. The first recorded move to exclude "the colored" in professional baseball occurred in 1882 when Adrian "Cap" Anson -- an Iowan, not a southerner -- came to Toledo with his Chicago White Stockings and ordered Toledo's Fleet Walker off the field. "Get that nigger off the field," he said, "or I will not allow my team to take the field." To its credit the Toledo management told Anson to buzz off, and despite Walker's presence Anson's team played.

Five years later Anson brought his team to Newark, where he again demanded that a black, Stovey, not be allowed to play. This time the Newark management caved in, and Stovey, not wishing to cause embarrassment to his employees, voluntarily left the field. Later when Anson learned that John Montgomery Ward was going to buy Stovey for the New York Giants, Anson successfully moved to bar black-skinned players from "organized baseball."

....The one manager with the guts to try to buck the barrier was New York Giant[s] manager John McGraw. McGraw, who began managing the Giants in 1902, had scouted a black star of the Columbia Giants by the name of Charley Grant, and after he signed him to a Giant contract, McGraw tried to fool reporters and everyone else by contending that Grant was not a Negro but rather a full-blooded Indian. But when the Giants played an exhibition in Baltimore, Grant's black followers packed the ballpark, and McGraw's deception was uncovered. Sometime later McGraw tried to sign a shortstop named Haley and get him through by saying he was Cuban. Again it didn't work. Not even the powerful McGraw could break baseball's immovable color bar.

....The first rumblings against the status quo began in the '40s, when black activist Paul Robeson confronted [Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain] Landis, demanding to know why black men ... were not permitted to play professional baseball. Robeson, who had been an All-American football player at Rutgers, told Landis that blacks played in football, track, and even professional croquet. Why not baseball?

With great solemnity, Judge Landis told Robeson that there was no rule on the books prohibiting a black man from joining a major league team. It was up to the owners to hire whom they pleased. Landis could get away with such a cavalier statement because he knew that the owners weren't about to give a Negro the opportunity. Chicago White Sox manager Jimmy Dykes had held a tryout for shortstop Jackie Robinson and pitcher Nate Moreland, but owner Charley Comiskey refused to sign them. Later, the Red Sox tried out Jackie Robinson, Marvin Williams, and Sam Jethroe. Coach Hugh Duffy wanted to sign all three of them, but owner Tom Yawkey refused to approve. For years Yawkey avoided signing Negro players, saying that he was waiting for a "great one." Having passed up a dozen or so Hall of Fame players, he became the last owner in either league to sign a black.

Then in the mid-1940s William Benswanger, owner of the Pittsburgh Pirates, tried to sign Josh Gibson, the Negro League's equivalent to Babe Ruth. Faced with an actual challenge, Commissioner Landis turned down the request, intoning, "The colored ballplayers have their own league. Let them play in their own league."

In 1944 Landis also prevented Bill Veeck from purchasing the cellar-dwelling Philadelphia Phillies and reviving them by hiring the best players from Negro League baseball. As soon as Landis heard the plan, he arranged for the Philadelphia owner, Gerry Nugent, to turn the team back to the National League so that Veeck would have to deal with National League President Ford Frick. Frick then allowed lumber dealer William Cox to buy the team for about half of what Veeck had offered. According to Veeck, Frick was bragging all over the baseball world that he had stopped Veeck from "contaminating the league."

....[W]ith Landis's death, the prime barrier against integrating the major leagues was gone. Under Happy Chandler, things would be different.

HAPPY CHANDLER: "For twenty-four years Judge Landis wouldn't let a black man play. I had his records, and I read them, and for twenty-four years Landis consistently blocked any attempts to put blacks and whites together on a big league field .... Now, see, I had known Josh Gibson and Buck Leonard and Satchel Paige, and, of course, Josh died without having his chance, and I lamented that, because he was one of the greatest players I ever saw ... and I thought that was an injustice.

"....I was named the commissioner in April 1945, and just as soon as I was elected commissioner, two black writers from the Pittsburgh Courier ... came down to Washington to see me. They asked me where I stood, and I shook their hands and said, 'I'm for the Four Freedoms, and if a black boy can make it in Okinawa and go to Guadalcanal, he can make it in baseball' ...."

From the time Chandler made his Four Freedoms statement in April 1945, Branch Rickey took just four months to select the man with the qualifications to break baseball's color barrier. Rickey, however, had been "making plans" long before then. Rickey had opposed discrimination since the turn of the century when he was the twenty-one-year-old baseball coach of Ohio Wesleyan University .... [R]acism in baseball embarrassed him, but he too knew that as long as Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis ... was commissioner, there was no way he would be able to do anything, and so he kept his thinking to himself as he waited for the day when Landis would step down.

...He knew there would be opposition when he acted, because no one -- not even his family -- was for it. When Rickey finally decided to go ahead with his bold plan to integrate major league baseball, the first person [he] confided in was Jane Rickey, his wife of many years....

Jane Rickey pleaded him; "Why should you be the one to do it? Haven't you done enough for baseball? Can't someone else do something for a change?"

His son, Branch, Jr., who was in charge of the [Brooklyn] Dodger farm system, told him, "It means we'll be out of scouting in the South."

"For a while," said Branch, Sr., "not forever."

Nothing would sway him. In August of 1945 Rickey sent scout Clyde Sukeforth to watch the Negro League's Kansas City Monarchs and to learn something about the team's shortstop, Jackie Robinson.

....Jackie became a star athlete in football, basketball, and baseball, first at Pasadena Junior College and then at UCLA, where he and Kenny Washington led his football team to within one yard of a Rose Bowl appearance. In basketball he was All-American honorable mention, and in track he broke a national record for the long jump previously set by his brother Mack, who had finished second to Jesse Owens in the 200-meter run in the 1936 Olympics in Berlin. Jackie was also a dominant baseball player. Whatever sport he played, he was hard to beat .... Robinson gained recognition as the nation's most versatile athlete, and some say that had he been white and from the East, he would have been rated as a better all-around athlete than the legendary Jim Thorpe.

....Jackie had applied for officer candidate school, and in January of 1943 he became a second lieutenant in the army, where he was a constant thorn in the side of his superiors .... Jackie had been asked to play on the Fort Riley [Kansas] football team, and he came out for practice, but before the first scrimmage ... [he] was virtually ordered to accept a pass to visit his folks back home. The real reason, he knew, was that the brass didn't want a Negro playing on the team. When Robinson came out for the baseball team, again he was denied the right to play.

....In November of 1944 ... the army gave Robinson an honorable discharge. In April of 1945, Robinson joined the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro American League for $400 a month ....

....When it was announced that the Brooklyn Dodgers had chosen Robinson as the first Negro to play in "organized baseball," his Kansas City teammates couldn't believe it. In forty-one games playing in the Negro American League, Robinson hit .345, hit ten doubles, four triples, and five home runs, and was the West's shortstop in the East-West all-star game, but most of them hadn't liked Robinson .... He was a California boy, a hothead who didn't know his place. He was college-educated, and they thought he felt superior to them. Also, he was a rookie, and his teammates felt that the first should have been a Negro League veteran such as Josh Gibson, Satchel Paige, Buck Leonard, or Monte Irvin, who later proved his worth with the New York Giants.

....What these Negro League ballplayers ... didn't understand was that Robinson's signing would ultimately mean the demise of the Negro Leagues. Most of the Negro ballplayers though that Robinson would be an isolated case. But it took only a couple of years for the full impact of Robinson's signing on the Negro League's to sink in.

In 1947, because of Robinson, attendance was down alarmingly for Negro League games. Nearly all Negro League teams lost money. Nineteen forty-eight was a disaster. The fans no longer showed up for games at all, and by 1949 the Negro League teams began trying to sell their players wholesale to keep from going under. In 1950 the New York Giants paid $15,000 to the Birmingham Black Barons for nineteen-year-old Willie Mays. In 1952 Milwaukee bought eighteen-year-old Henry Aaron from the Indianapolis Clowns, and in 1953 the Cubs bought twenty-two-year-old Ernie Banks from the Kansas City Monarchs.

When the major league teams began buying youngsters, the Negro Leagues were doomed. The Negro Leagues could stand the loss of a Robinson, or maybe even a Satchel Paige. But when all of a sudden the kids were going to the majors, the Negro Leagues didn't have any talent coming up, and that's what killed them. Two-and-a-half years after Mays came up in 1951, the Negro Leagues folded.

On October 23, 1945, it was announced that Jackie Robinson had signed a contract to play for the [Dodger AA] Montreal Royals for the 1946 season. In the North there was only a ripple of reaction, but for the masses of disillusioned Negroes in the South, Jackie Robinson's entry into baseball meant so much more. Because not only was Robinson going to play baseball, but he was going to play it with whites. He was going to get the opportunity to prove to the white community that he could be just as good as they were ...

-- Peter Golenbock

Bums: An Oral History of the Brooklyn Dodgers

2nd INNING

The First Truly Exciting All-Star Game

In Detroit, where the [1941] All-Star game was to be played ... [m]any of the All-Star players had "candid cameras," as the newly popular 35-mm cameras were called, and some had movie cameras. All of them took pictures of [Joe] DiMaggio. When the All-Star teams were introduced he and [Bob]Feller received the greatest applause from the Detroit crowd (except for Rudy York, the lone Tiger in the American League lineup.)

DiMaggio batted third for the American League while [Ted] Williams hit fourth. Feller pitched the first three innings and shut down the National League with only one hit. Williams drove in the first run of the game with a double off Paul Derringer in the fourth, and after six innings the American League led 2-1.

Then the presumptive hero of the game emerged. He was Arky Vaughan, the renowned shortstop of the Pittsburgh Pirates .... Vaughan hit a two-run homer in the seventh inning to put the National League ahead 3-2, and in the eighth he hit another two-run homer to make the score 5-2.

The American League, the dominant league in those days, had won six of the first seven All-Star games, but the Nationals had won the year before when they shut out the Americans 4-0. Then the Nationals won the World Series for the first time in six years, and now they were winning the All-Star game again. People gave credit for this success to Bill McKechnie, the Cincinnati Reds' manager, who piloted the National League All-Stars in both 1940 and 1941 ....

DiMaggio had not yet had a hit, not that it mattered as far as his [45-game hitting] streak was concerned. The All-Star game was an exhibition not a regular-season game. But the crowd wanted a hit from Joe and yelled for him to get one each time he batted, and it felt let down each time he failed. In the eighth inning, to the joy of the crowd, Joe doubled, and a moment later, after [Claude] Passeau struck out Williams, he scored on his brother Dominic's double. But that was all the American League could do. The Nationals still led 5-3 going into the last half of the ninth.

McKechnie ... let Passeau stay in the game for a third inning. The big righthander ... got the first man out on a pop-up to Billy Herman, who was playing second base for the Nationals. But Ken Keltner hit a hard ground ball to short that took a bad hop and hit Eddie Miller, who had taken over for Vaughan, on the shoulder. Keltner was safe. Joe Gordon followed with a clean single to right. Passeau went to a three-and-two count on Cecil Travis and walked him, filling the bases with one out, and the great DiMaggio came to bat.

....But DiMaggio hit a bouncing ball to the shortstop, a grounder made to order for a fast, game-ending double play. Miller fielded it, hurried his throw and tossed the ball a little off-line to Herman at second base. Herman, veteran of a thousand double plays, caught the ball just as Travis slid in hard and relayed it a little awkwardly to first base. They missed the double play. Herman's throw pulled the first baseman off the bag and DiMaggio, running hard as always, was safe. The run scored. The game, which seemed over, was not over. The American League still had life.

Gordon was on third base, DiMaggio on first. There were two out, the score was 5-4 in favor of the Nationals, and Williams was up. He was a lefthanded hitter opposing the righthanded Passeau, who was facing his sixth batter in this third inning of pitching, and yet McKechnie stayed with him. He remembered that Passeau had struck out Williams in the eighth.

"Passeau was always tough," Williams said in his autobiography. "He had a fast tailing ball he'd jam a lefthanded hitter with, right into your fists, and if you weren't quick he'd get it past you...."

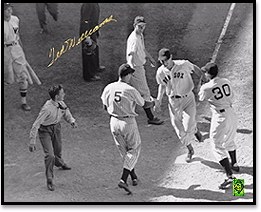

The first pitch was low for a ball. Williams fouled the second down the first-base line. The third was high and inside for ball two. The fourth was the tailing fast ball Williams spoke of, in on the fists. Williams was waiting for it .... He hit the ball. Briggs Stadium in Detroit was famous as an easy home-run park, but Williams' towering blast down the right-field line ... would have been a home run anywhere. It soared on a high arc and hit against the green woodwork at the front of the roof high in right field. Three runs scored .... [T]he American League had won, 7-5. Williams, laughing, clapping his hands, leaping like a young colt, bounded his way around the base paths and touched home plate. The All-Stars on the American League bench ran ... like small boys to pound Williams on the back, pat him, shake his hand ....

There had been dramatic moments in earlier All-Star games --Ruth's home run in 1933, Carl Hubbel striking out five great hitters in a row in 1934, Feller coming on in relief in 1939 with the bases loaded and one out and ending the uprising with one pitch that was hit into an inning-ending double play. But Williams' homer, coming after Vaughan's two, made this the first truly exciting All-Star game, and in half a century since there hasn't been another to top it. There had been dramatic moments in earlier All-Star games --Ruth's home run in 1933, Carl Hubbel striking out five great hitters in a row in 1934, Feller coming on in relief in 1939 with the bases loaded and one out and ending the uprising with one pitch that was hit into an inning-ending double play. But Williams' homer, coming after Vaughan's two, made this the first truly exciting All-Star game, and in half a century since there hasn't been another to top it. ....If there was a precise moment when Williams was fully accepted by the baseball fraternity, this was it.

"I'm delighted," he kept saying. "Boy, was I glad to beat those guys this way. That's a moment I'll never forget."

He never did. He played another sixteen seasons, batted .400, won six batting titles, won the Most Valuable Player award as his team won the pennant, hit three more homers in All-Star play, hit another 450 homers in regular-season play, and was elected to the Hall of Fame. When it was all over he said the home run in Detroit was "the most thrilling hit of my life. It was a wonderful, wonderful day for me."

--Robert W. Creamer

Baseball in '41

3rd INNING

From the Editor: The Hot Stove

Maybe back in the day there wasn't much for the ballplayers, managers, coaches and owners to do but sit around a hot stove on a winter's day and talk about the last campaign. These days, though, there is nearly as much activity in the weeks following the Fall Classic and before Opening Day as occurs during the season.

In November there are numerous baseball awards to be bestowed -- the Gold Gloves for both leagues, the Rookies of the Year for both leagues (11.13), The NL Cy Young Award (11.14) and the AL CYA (11.16), the Managers of the Year for both leagues (11.15), the National League's Most Valuable Player (11.20) and the AL MVP (11.21). In November there are numerous baseball awards to be bestowed -- the Gold Gloves for both leagues, the Rookies of the Year for both leagues (11.13), The NL Cy Young Award (11.14) and the AL CYA (11.16), the Managers of the Year for both leagues (11.15), the National League's Most Valuable Player (11.20) and the AL MVP (11.21). Between October 28 and November 11 players whose contracts have expired and who have at least six years of major league service may file for free agency. Beginning on November 12, free agents and ballclubs may discuss deals. Ballclubs can offer arbitration to their players who have filed for free agency up through December 1. By offering arbitration the ballclub qualifies for draft pick compensation if the player signs with another club. A free agent has until December 7 to accept or decline arbitration. By accepting he ceases to be a free agent, and the two parties will either agree on a contract or the salary of the player will be determined by an arbitrator. The salary arbitration filing period is January 5-15, 2007.

In 2006 the Winter Meetings are being held in Orlando, FL. For four days owners and general managers can talk shop and sign free agents and work out trade details. During the meeting the ballclubs participate in the Rule 5 Draft. Clubs can choose minor league players from other teams, but in doing so they must keep those players on their major league roster all season. This was put in place to allow young players stuck in one organization's minor league network to get a shot in The Show.

Players with more than three but less than six years of major league service must be offered a contract by December 12. If a contract is offered to a player, he remains the property of that club. If he isn't, he becomes a non-tender free agent.

Salary arbitration hearings are held between February 1-21. Shortly after that, it's off to spring training, and we're all gearing up for a brand new season of baseball.

IMAGE: The Cy Young Award

-- J. Manning

4th INNING

The Man With No Strike Zone

As owner of the hapless St. Louis Browns [in 1951, Bill] Veeck decided to create a little excitement in the midst of another last-place season. On August 19, the Browns were at home entertaining the Detroit Tigers in a doubleheader.

The first game was uneventful enough. Then came the nightcap. In the Browns' half of the first inning, outfielder Frank Saucier was due to lead off. But a pinch hitter appeared out of the St. Louis dugout. Suddenly, everyone in the ballpark stood to get a closer look. It seemed as if the Browns were sending a small boy to the plate!

The batter was only three feet, seven inches tall, weighed sixty-five pounds, and had the number 1/8 on his uniform shirt. Plate umpire Ed Hurley called time immediately and demanded an explanation. That's when Browns' manager Zach Taylor came out of the dugout and showed Hurley a major league contract. The batter was only three feet, seven inches tall, weighed sixty-five pounds, and had the number 1/8 on his uniform shirt. Plate umpire Ed Hurley called time immediately and demanded an explanation. That's when Browns' manager Zach Taylor came out of the dugout and showed Hurley a major league contract. Meet Eddie Gaedel, a twenty-six-year-old midget, who had actually signed to play for the Browns. Only Bill Veeck would come up with something like this. Umpire Hurley had no choice but to allow Gaedel to bat. The contract was valid and the three-foot, seven-inch [batter] was a legitimate player.

Gaedel took his place in the batter's box and went into a deep crouch. The strike zone was reduced to microscopic size and Tiger pitcher Bob Cain couldn't find it. He walked Eddie Gaedel on four pitches, whereupon Manager Taylor sent in a pinch runner.

No one knows whether Veeck intended to use Gaedel as a pinch hitter in future situations where a walk was needed to help win a game. He didn't get the chance. American League president Will Harridge would not approve Gaedel's playing contract, claiming that Gaedel playing for the Browns came under the heading of "conduct detrimental to baseball."

So Eddie Gaedel never appeared in a major league game again, but his name will forever be remembered, thanks once more to master showman Bill Veeck. Gaedel, however, would have preferred to remain with the team.

"I felt like Babe Ruth when I walked out on the field that day," he told reporters.

-- Bill Gutman

Strange & Amazing Baseball Stories

NOTE: Gaedel made a few other appearances on the baseball field. In 1959 he and several other midgets, dressed as spacemen, showed up at Comiskey Park in a helicopter that landed behind second base, and in 1961 he and seven other midgets acted as vendors as Veeck responded to complaints that vendors blocked the view of fans. Later that same year Gaedel was mugged in Chicago and died of a heart attack at the age of 36 -- ed.

5th INNING

What the Black Sox Did for Baseball

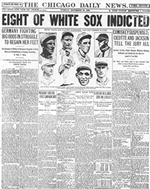

The second pitch Ed Cicotte of the White Sox threw in the first game of the 1919 World Series hit Cincinnati's leadoff man. New York gamblers got the signal: The Series was fixed ....

The Black Sox scandal involved two timeless themes of art: love and regret. In that instance, it was love of vocation and regret about losing it. The most poignant figure was Shoeless Joe Jackson, the illiterate natural who compiled the third-highest batting average in history and who was so reflexively great that even when throwing the Series he could not stop himself from hitting .375 and setting a Series record with twelve hits. The Black Sox scandal involved two timeless themes of art: love and regret. In that instance, it was love of vocation and regret about losing it. The most poignant figure was Shoeless Joe Jackson, the illiterate natural who compiled the third-highest batting average in history and who was so reflexively great that even when throwing the Series he could not stop himself from hitting .375 and setting a Series record with twelve hits. The scandal is a window in a dank basement of American history. In 1919, Americans were feeling morally admirable, if they did say so themselves, and they did. They had been on the winning side in "the war to end war." The fixed Series occurred three months before the beginning of a misadventure in moralism, Prohibition.

But gambling was as American as the gold rush -- the dream of quick riches -- and when the government closed racetracks during the war, gamblers turned to baseball, which was then America's biggest entertainment industy. Hotel lobbies where teams stayed teemed with gamblers. "Hippodroming" was the nineteenth-century word for throwing games, and in postwar America there was a new brazenness by gamblers.

On September 10, 1920, various Wall Street brokerage houses received "flashes" on their news wires: Babe Ruth and some teammates had been injured in an accident en route to Cleveland. Quickly the odds on that game changed, and the gamblers -- the source of the lie -- cleaned up.

The White Sox conspirators assumed they would get away with their plot because they assumed, almost certainly correctly, that other major leaguers had gotten away with fixes. In response to the scandal, the team owners, frightened about the possible devaluation of their franchises, rushed out and bought some virtue in the person of a federal judge to serve as baseball's first commissioner.

Kenesaw Mountain Landis, with his shock of white hair over craggy features and his mail-slot mouth, looked like a statue of Integrity Alerted .... Landis was a tobacco-chewing bourbon drinker who would hand out stiff sentences to people who violated prohibition. He had a knack for self-dramatizing publicity. He ... tried to extradite Kaiser Wilhelm* on a murder charge because a Chicagoan died when a German submarine sank the Lusitania.

Landis barred from baseball eight Sox players, including one who merely knew about the conspiracy but did not report it. It was rough justice. Nothing happened to the gamblers, and some of the players were guilty primarily of stupidity and succumbing to peer pressure. Most of them were cheated out of most of the money gamblers had promised to them, and only one player made much ($35,000). But roughness can make justice effective. Baseball's gambling problems were cured.

The 1920s, the dawn of broadcasting and hence of hoopla, washed away memories of the scandal. Those years were the Golden Age of American sport -- Babe Ruth, Jack Dempsey, Gene Tunney, Red Grange, Knute Rockne, Bobby Jones, Bill Tilden, Man o' War.

....Baseball put its house in order because of the Black Sox .... [I]t is well to consider how far we have come in the ... years since Chicago children began their sandlot games with the cry "PLAY BAIL!"

-- George F. Wills

October 6, 1988

Bunts

6th INNING

Stats: Most Hits by Decade (through the 1980s)

1893-99: Jesse Burkett 1,462 ... Ed Delahanty 1,431 ... Willie Keeler 1,346

1900-09: Honus Wagner 1,847 ... Sam Crawford 1,677 ... Nap Lajoie 1,660

1910-19: Ty Cobb 1,949 ... Tris Speaker 1,821 ... Eddie Collins 1,682

1920-29: Rogers Hornsby 2,085 ... Sam Rice 2,010 ... Harry Heilmann 1,924

1930-39: Paul Waner 1,959 ... Charlie Gehringer 1,865 ... Jimmie Foxx 1,845

1940-49: Lou Boudreau 1,578 ... Bob Elliott1,563 ... Dixie Walker 1,512

1950-59: Richie Ashburn 1,875 ... Nellie Fox 1,837 ... Stan Musial 1,771

1960-69: Roberto Clemente 1,877 ... Hank Aaron 1,819 ... Vada Pinson 1.776

1970-79: Pete Rose 2,045 ... Rod Carew 1,787 ... Al Oliver 1,686

1980-89: Robin Yount 1,731 ... Eddie Murray 1,642 ... Willie Wilson 1,636

Most Hits in a Career:

Pete Rose 4,256 ... Ty Cobb 4,189 ... Hank Aaron 3,771 ... Stan Musial 3,630 ... Tris Speaker 3,514 ... Carl Yastrzemski 3,419 ... Honus Wagner 3,415 ... Paul Molitor 3,319 ... Eddie Collins 3,315 ... Willie Mays 3,283

Most Hits in a Single Season:

Pete Browning (1887) 275 ... Tip O'Neill (1887) 275 ... Ichiro Suzuki (2004) 262 ... George Sisler (1920) 257 ... Denny Lyons (1887) 256 ... Lefty O'Doul (1929) 254 ... Bill Terry (1930) 254 ... Al Simmons (1925) 253 ... Oyster Burns (1887) 251 ... Rogers Hornsby (1922) 250 ... Chuck Klein (1930) 250

7th INNING

Year in Review: 1912

Few seasons have been as turbulent as 1912. Along with the Detroit player strike, Fenway Park and Tiger Stadium ... both opened for business. For the first time in history, a Washington team challenged for a pennant. Huge personnel turnover also occurred, further evidence that it was a transitional season. The New York Highlanders used a record 44 players, and even the A's needed 17 pitchers in a vain attempt to defend their championship.

The A's sag enabled Boston to claim its first AL flag since 1904. In the interim the team had adopted a new nickname -- the Red Sox -- and unearthed in Tris Speaker and Joe Wood the best defensive outfielder and the best young pitcher in the game. When Wood went an astounding 34-5 and Speaker hit .383, the Crimson Hose rose from fourth place in 1911 to first, drilling 105 victories to set a new AL mark.

As usual, John McGraw and the New York Giants were in the thick of things in 1912

In the NL, however, the more things changed the more they remained the same. Though many new faces dotted the loop, the pennant race still belonged exclusively to the Giants, the Pirates, and the Cubs while the other five clubs scrapped for the remaining spot in the first division. In 1912, the Cincinnati Reds earned the privilege of finishing a remote fourth to John McGraw's Giants, and even Pittsburgh, in second, staggered home 10 games back. The best offensive team in the majors with a .286 BA and 823 runs, the Giants also flaunted the deepest pitching staff after rookie spitballer Jeff Tesreau was added and banged out 17 wins and a loop-leading 1.96 ERA.

-- David Nemec & Saul Wisnia

Baseball: More Than 150 Years

8th INNING

The 1912 World Series

Boston Red Sox (4) v New York Giants (3)

October 8-16

Fenway Park (Boston), Polo Grounds (New York)

A World Series scoreboard, downtown San Diego, October 5, 1912

Favored in the Series because of their depth and experience, the Giants fell behind Boston, 3-1. Backed against the wall, Rube Marquard and Tesreau then won on successive days to knot the Series at 3-all and set up the first-ever winner-take-all postseason game. McGraw summoned Christy Mathewson and Boston skipper Jake Stahl called on Hugh Bedient. The two had dueled four days earlier to a 2-1 Boston win. It seemed Mathewson's destiny to triumph 2-1 when the Giants pushed home a run in the top of the 12th, but he then was victimized by two egregious defensive lapses in the bottom of the frame. The first, Fred Snodgrass's muffed fly ball, was more highly publicized, but it was really the foul pop that Speaker hit that went uncaught later in the inning that ultimately permitted Boston to plate two unearned runs and gain a 3-2 victory in one of the baseball's greatest postseason games.*

Game 1: Boston 4, New York 3

Game 2: Boston 6, New York 6

Game 3: New York 2, Boston 1

Game 4: Boston 3, New York 1

Game 5: Boston 2, New York 1

Game 6: New York 5, Boston 2

Game 7: New York 11, Boston 4

Game 8: Boston 3, New York 2

BOSTON: Neal Ball (ph), Hugh Bedient (p), Hick Cady (c), Bill Carrigan (c), Ray Collins (p), Clyde Engle (ph), Larry Gardner (3b), Charley Hall (p), Olaf Henriksen (ph), Harry Hooper (of), Duffy Lewis (of), Buck O'Brien (p), Tris Speaker (of), Jake Stahl (1b), Heinie Wagner (ss), Joe Wood (p), Steve Yerkes (2b). Mgr: Jake Stahl

NEW YORK: Red Ames (p), Beals Becker (ph), Doc Crandall (p), Josh Devore (of), Larry Doyle (2b), Art Fletcher (ss), Buck Herzog (3b), Rube Marquand (p), Christy Mathewson (p), Moose McCormick (ph), Fred Merkle (1b), Chief Meyers (c), Red Murray (of), Tillie Shafer (ss), Fred Snodgrass (of), Jeff Tesreau (p), Art Wilson (c). Mgr: John McGraw

Game 2, tied at 6, was called in the 11th inning when night fell. It was the second World Series tie game (see 1907).

* SEE "Losing A Big One" -- Issue # 3, 1st Inning -- for more on the seventh game -- ed.

9th INNING

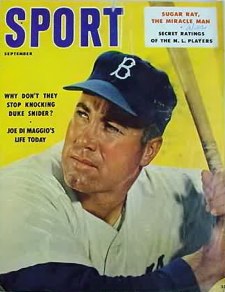

Player Profile: Duke Snider

Nickname: "The Duke of Flatbush" "The Silver Fox"

Born: September 19, 1926 (Los Angeles, CA)

ML Debut: April 17, 1947

Final Game: October 3, 1964

Bats: Left Throws: Right

6'0" 190 lb

Hall of Fame: 1980 (Baseball Writers; 333 votes on 385 ballots, 86.49%)

The advent of television coincided with the coming of age of the Dodger center fielder, Edwin "Duke" Snider, who more than any other Dodger benefited from the small rectangular box that was invading living rooms, bedrooms, stores, and bars in Brooklyn and across America. He was young, handsome, and he had a winning smile. Almost overnight the prematurely silver-haired Duke Snider became Brooklyn's matinee idol. The advent of television coincided with the coming of age of the Dodger center fielder, Edwin "Duke" Snider, who more than any other Dodger benefited from the small rectangular box that was invading living rooms, bedrooms, stores, and bars in Brooklyn and across America. He was young, handsome, and he had a winning smile. Almost overnight the prematurely silver-haired Duke Snider became Brooklyn's matinee idol. ....Snider had grown up in Los Angeles, played only one full season in the minors, in 1944, and after two years in the service played for St. Paul the tag end of 1947 and in 1948 for Montreal, where he drove in seventy-seven runs in seventy-seven games .... Snider had raw talent [and] had a powerful swing at the plate ....

The Duke played with intensity and abandon, and his physical skills were exceptional. When a ball stayed in the ballpark, the Duke would find a way to catch it. The parks then had different nooks and crannies and stands jutting out on the field, and in an old stadium like Philadelphia's Connie Mack Stadium, where a player could jump up and catch balls that would have been in the third or fourth row, Duke would make plays that were otherwordly, running full speed and never getting hurt and leaping and hitting the wall and amazing the fans by catching the balls that would have been home runs.

And starting in 1953, the first of five consecutive years when he hit forty or more home runs, Duke Snider was regarded as the premier power hitter on what some regard as the most powerful lineup ever to grace a National League diamond. At Ebbets Field he hit towering home runs into Bedford Avenue, and every once in a while he would send the baseball clear across the street, clattering through the plate glass windows of Dodger Dodge. Any left-handed kid growing up in Brooklyn wore number 4 on the back of his t-shirt and demanded that he play center field on his team.

....BILL REDDY: "There were only two center fielders in Metropolitan New York, Duke Snider and [the New York Giants'] Willie Mays. Whenever we debated about the greatest center fielder, Mantle's name was in there, you had to put it in, but Mantle was just a name you threw in as a sop to the Yankee fans that might be listening. Believe me, Mantle never figured in at all, not one iota. It was Snider and Mays, and every day we would scan the papers to see which guy made the most spectacular catch or the most hits that day...."

Duke, like so many of the players, lived in Brooklyn. He was one of dem, and there were times when he would come home after a ballgame and play stickball with the kids in the street.

The fans loved him, though they sensed he was flawed. Somehow they knew he hated to hit against left-handed pitchers, and they knew that in October Mantle's team won and his team didn't. In the backs of their minds always was the disquieting sense that no matter how good Snider was, somehow he should be better. Which demonstrated the perspicacity of the Dodger fans. For during his entire career, Snider fretted and worried about the same thing. When Snider was on the field, winning was all he thought about. He was consumed with the notion of winning, for to him losing was a sign of personal weakness. An error was a sign of weakness. Striking out was a sign of weakness ....

....Duke Snider, who personified the Dodger power, ironically had an inferiority complex. As a batter he had expected to get a hit every single time at bat, and when didn't he would sulk. If an opposing fielder made a great play on a long hit, he would complain to the heavens about his bad luck. For his entire career, Duke Snider carried on in this manner, always raging and decrying his luck. It had been Snider whose rope into center field should have won the pennant for the Dodgers in 1950. Except that Cal Abrams got thrown out at home. Typical Snider luck. As great as he was, no matter how well he was doing, Duke Snider always felt that his luck should have been better.

--Peter Golenbock

Bums: An Oral History of the Brooklyn Dodgers

...Snider was baseball's most prolific home run hitter of the 1950s, clouting 326 round-trippers in the decade. Included in the total were five straight seasons of 40 or more and a league-leading 43 in 1956. He drove in 100 runs six times, with an NL high of 136 in 1955. He also scored 100 runs six times, including three straight league-leading totals. Although he struck out more than any other league batter three times, Snider was no all-or-nothing hitter. He paced the league in hits in 1950, averaged better than .300 seven times, and ended his career at .295 only because of his final desultory seasons. In both the 1952 and 1955 World Series he hit four home runs. While not gifted with the speed of a Mays or mantle and given to allowing hits to roll out to him, he was an exceptional defensive outfielder. His leaping catch of a Yogi Berra drive against the Yankee Stadium auxiliary scoreboard in the fifth game in 1952 ranks as one of the greatest World Series fielding plays.

Nobody was more affected than Snider by the Dodgers move from Brooklyn to Los Angeles after the 1957 season. Instead of Ebbets Field's friendly right field wall, he had to deal with the Yellowstone distances of the Coliseum, and he tailed off precipitously. After some time in a platoon role with the Dodgers, he was sold to the Mets in a gate-appeal move by the expansion New York franchise .... The outfielder ended his 18-year career in 1964 with a short stint with the Giants.

....In 1956 he attracted attention for telling Collier's magazine that he played baseball for money. The declaration horrified baseball executives and sportswriters for, as one of them put it, "disillusioning young fans."

--Donald Dewey & Nicholas Acocella

The New Biographical History of Baseball

Snider hit the last home run recorded at Ebbets Field, on September 22, 1957.

Snider is the Dodgers franchise record-holder for home runs (389), RBIs (1,271) and extra-base hits (814).

EXTRA INNINGS

They Played the Game

Sam Thompson

(1885-1898, 1906)

Thompson was the only 19th century player to average over two home runs -- 2.12, to be exact -- per 100 at-bats. He also has the second-most RBI in the 19th century: 165 in 1895, and set a pre-1893 record with 166 RBI in 127 games in 1887, the year his Detroit Wolverines won an NL pennant and defeated the AA champions, the St. Louis Browns, in a "world series". In 1894 Thompson was playing for the Philadelphia Phillies when he set an all-time record with 1.38 RBI per game. (He broke that record the very next year.) When Thompson signed his first professional contract in 1884, he was paid $2.50 a game.

"Big Sam"

BORN 3.5.1860 (Danville, IN)

HALL of FAME 1974

.331, 127, 1299

Frank Robinson

(1956-76)

(HoF) After winning NL MVP honors in 1961, Robinson was traded by the Cincinnati Reds to Baltimore in '66. That year Robinson won the Triple Crown (.316, 49, 133), hit a pair of homers in the World Series, and was voted the AL MVP -- becoming the first and only player to win that honor in both leagues.

BORN 8.31.35 (Beaumont, TX)

HALL of FAME 1982

.294, 586, 1812

All-Star 1956, 1957, 1959, 1961, 1962, 1965, 1966, 1967, 1969, 1970, 1971, 1974

1956 NL ROY 1961 NL MVP 1966 AL MVP 1966 AL Triple Crown 1966 ML WS MVP 1971 ML AS MVP

Billy Herman

(1931-43, 1946-47)

This Hall of Famer had an inauspicious big league debut. In his first at-bat he tipped a Si Johnson pitch and the ball hit the ground and bounced up to strike him on the head, knocking him unconscious. He was carried off the field on a stretcher.

BORN 7.7.09 (New Albany, IN)

HALL of FAME 1975

.304, 47, 839

All-Star 1934, 1935, 1936, 1937, 1938, 1939, 1940, 1941, 1942, 1943

Paul Hines

(1872-1890)))

The first Triple Crown winner in major league history was outfielder Hines (Providence Grays), due to his 1878 marks of .358, 4, 50. He never knew about the honor, however. In fact, Milwaukee's Abner Dalrymple was awarded the NL batting crown that year. Only later did statisticians discover that the 1878 calculations had been erroneous. Hines was aware of the Triple Crown he won in 1879 with marks of .357, 2, 52. He was the first repeat Triple Crown winner.

BORN 3.1.1865 (Virginia)

.302, 57, 885

1878 NL Triple Crown

Pud Galvin

(1875-92)

Hall of Fame pitcher Galvin holds the 19th century record of 361 wins, and pitched in 705 games between 1871 and 1892. On August 4, 1882 he won the most lopsided no-hitter in history when his Buffalo Bisons defeated Detroit 18-0.

BORN 12.25.1856 (St. Louis, MO)

HALL of FAME 1965

364-310, 2.86

THIS MATERIAL IS REPRODUCED FOR NON-PROFIT EDUCATIONAL AND SCHOLARLY PURPOSES ONLY, WHICH COMPLIES WITH THE DOCTRINE OF FAIR USE AS EXPRESSED IN THE COPYRIGHT ACT OF 19 OCTOBER 1976, EFFECTIVE 1 JANUARY 1978 (TITLE 17 OF THE UNITED STATES CODE, PUBLIC LAW 94-553, 90 STAT. 2541.)

|