9 Innings 9 InningsA Baseball History Reader

J. Manning, Editor

|

Issue # 12: October 31, 2006

Easy Lessons ... The Knothole Gang and Ladies' Day ... The 2006 Super Team ... Goodbye, Tiger Stadium ... Joe Wood: My Greatest Season ... Stats: Brothers ... Year in Review: 1911 ... The 1911 World Series ... Player Profile: Tommy Henrich ... Baseball Dictionary (Babe Ruth Baseball - backup slider)

|

"A hot dog at the ballgame beats roast beef at the Ritz."

-- Humphrey Bogart

1st INNING

Easy Lessons

[1984] In Winter Haven, on the very first day of this spring jaunt, I found Ted Williams out in right-field foul ground teaching batting to Von Hayes -- a curious business, since the Splendid Splinter , of course, is a spring batting instructor for the Red Sox, and Hayes is the incumbent center fielder of the Phillies. Hayes was accompanied by Deron Johnson, the Philadelphia batting coach, and the visit, I decided, was in the nature of medical referral -- a courtesy second opinion extended by a great specialist to a colleague from a different hospital (or league). Von Hayes is a stringbean -- six feet five, with elongated arms and legs -- and his work at the plate this year will be the focus of anxious attention from the defending National League Champion Phillies, who are in the process of turning themselves from an old club into a young one in the shortest possible time. Since last fall, they have parted with (among others) Pete Rose, Joe Morgan, Tony Perez, and veteran reliever Ron Reed, and later this spring they traded away Gary Matthews, their established left fielder. (Matthews, in fact, was intently listening in on Ted Williams' talk to his teammate Hayes), to the Cubs. Two years ago, in his first full year in the majors, Von Hayes hit fourteen homers and batted in eighty-two runs for the Cleveland Indians -- sufficient promise to encourage the Phillies to give up five of their own players (including the wonderful old Manny Trillo and the wonderful young Julio Franco) for him. Last year, Hayes, troubled with injuries (and perhaps unsettled by the nickname Five-for-One, bestowed on him by Pete Rose, batted a middling-poor .265, with six homers -- reason enough for a call to Dr. Ted. [1984] In Winter Haven, on the very first day of this spring jaunt, I found Ted Williams out in right-field foul ground teaching batting to Von Hayes -- a curious business, since the Splendid Splinter , of course, is a spring batting instructor for the Red Sox, and Hayes is the incumbent center fielder of the Phillies. Hayes was accompanied by Deron Johnson, the Philadelphia batting coach, and the visit, I decided, was in the nature of medical referral -- a courtesy second opinion extended by a great specialist to a colleague from a different hospital (or league). Von Hayes is a stringbean -- six feet five, with elongated arms and legs -- and his work at the plate this year will be the focus of anxious attention from the defending National League Champion Phillies, who are in the process of turning themselves from an old club into a young one in the shortest possible time. Since last fall, they have parted with (among others) Pete Rose, Joe Morgan, Tony Perez, and veteran reliever Ron Reed, and later this spring they traded away Gary Matthews, their established left fielder. (Matthews, in fact, was intently listening in on Ted Williams' talk to his teammate Hayes), to the Cubs. Two years ago, in his first full year in the majors, Von Hayes hit fourteen homers and batted in eighty-two runs for the Cleveland Indians -- sufficient promise to encourage the Phillies to give up five of their own players (including the wonderful old Manny Trillo and the wonderful young Julio Franco) for him. Last year, Hayes, troubled with injuries (and perhaps unsettled by the nickname Five-for-One, bestowed on him by Pete Rose, batted a middling-poor .265, with six homers -- reason enough for a call to Dr. Ted. "Lemme see that," Ted Williams was saying, and he took Hayes' bat and then hefted it lightly, like a man testing a new tennis racquet. "Well, all right, if you're really strong enough," he said, giving it back. "But you don't need a great big bat, you know. Stan Musial always used a little bitty drugstore model. So what do you want? You know what Rogers Hornsby told me forty-five years ago? It was the best batting advice I ever got. 'Get a good ball to hit!' What does that mean? It means a ball that does not fool you, a ball that is not in a tough spot for you. So then when you are in a tough spot, concede a little to that pitcher when he's got two strikes on you. Think of trying to hit it back up the middle. Try not to pull it every time. Harry Heilmann told me he never became a great hitter until he learned to hit inside out. I used to have a lot of trouble in here" -- he showed us an awkward inside dip at the ball with his own bat -- "until I moved back in the box and got a little more time for myself. Try to get the bat reasonably inside as you swing, because it's a hell of a lot harder to go from the outside in than it is to go the other way around."

Hayes, who looked pale with concentration, essayed a couple of left-handed swings, and Williams said, "Keep a little movement going. Keep your ass loose. Try to keep in a quick position to swing. When your hands get out like that, you're just making a bigger arc."

Hayes swung again -- harder this time -- and Williams said, "That looks down to me. You're swingin' down on the ball."

Hayes looked startled. "I thought it was straight up," he said. He swung again, and then again.

"Well, it's still down," Ted said quietly. "And see where you're looking when you swing. You're looking at the ground about out here." He touched the turf off to Hayes' left with the tip of his bat. "Look out at that pitcher -- don't take your eyes off him. That and --" Williams cocked his hips and his right knee and swung at a couple of imaginary pitches, with his long, heavy body uncocking suddenly and thrillingly and then rotating with the smooth release of his hips. His hands, I saw now, were inside, close to his body, while Hayes' hands had started much higher and could not come back for a low inside pitch with anything like Ted's ease and elegance. Nothing to it. Hayes, who has a long face, looked sepulchral now, and no wonder, for no major leaguer wants to retinker his swing -- not in the springtime, not ever -- and Williams, sensing something, changed his tone. "Just keep going," he said gently to the young man. "Everybody gets better if they keep at it."

Hayes kept at it, standing in and looking out at an imaginary pitcher, and then cocking and striding, while Williams stood and watched with Deron Johnson, now and then murmuring something to the other coach and touching his own hip or lifting his chin or cocking his fists by way of illustration -- a sixty-five-year-old encyclopedia of hitting, in mint condition: the book.

When I left, he was deep in converse with Gary Metthews, who had asked about the best response to a pitcher's backup slider after two fastballs up and in. "Why, take that pitch, then!" cried Ted. "Just let it go by. Don't be so critical of yourself. Don't try to be a .600 hitter all the time. Don't you know how hard this all is?"

*****

I accompanied the Red Sox down to Sarasota to watch Tom Seaver work against them the following afternoon -- his first American League innings ever. Seaver, as most of the Northern Hemisphere must know by now, was snatched away from the Mets over the winter when that club carelessly failed to place him on its protected twenty-six man roster prior to a "compensation draft" -- a process that permits a team (in this case, the White Sox) that has lost a so-called Type A player to free agency to select as recompense a player from a pool of players with other teams that have signed up for the plan. This misshapen schema is a monster child spawned by the owners as part of the settlement of the player strike of 1981, and there is considerable evidence that its headstrong fathers may now wish to disinherit it.... I accompanied the Red Sox down to Sarasota to watch Tom Seaver work against them the following afternoon -- his first American League innings ever. Seaver, as most of the Northern Hemisphere must know by now, was snatched away from the Mets over the winter when that club carelessly failed to place him on its protected twenty-six man roster prior to a "compensation draft" -- a process that permits a team (in this case, the White Sox) that has lost a so-called Type A player to free agency to select as recompense a player from a pool of players with other teams that have signed up for the plan. This misshapen schema is a monster child spawned by the owners as part of the settlement of the player strike of 1981, and there is considerable evidence that its headstrong fathers may now wish to disinherit it.... The first glimpse of Tom in Chisox motley -- neon pants, stripes, the famous No. 41 adorning his left groin -- was a shock, though, and so was the sight of him in pre-game conversation with his new batterymate, Carlton Fisk. I took a mental snapshot of the two famous Handsome Harrys and affixed to it the caption "Q: What's wrong with this picture?" (A: Both men are out of uniform.) Then the game started, and Seaver's pitching put an end to all such distractions....

In the clubhouse after his stint, Seaver declared himself satisfied with his work -- perhaps more than satisfied .... He went over the three innings almost pitch by pitch, making sure that the writers had their stories, and they thanked him and went off. A couple of us stayed on while Tom ... talked about tempos of early throwing in the first few days of spring -- a murmured "one, two, three-four .. .one, two, three-four" beat with the windup as his body relearned rhythm and timing. He went on to the proper breaking point of the hands -- where the pitching hand comes out of the glove -- which for him is just above and opposite his face. Half undressed, he was on his feet again and pitching for us in slow motion, in front of his locker.

"What you don't want is a lateral movement that will bring your elbow down and make your arm drop out, because what happens then is that your hand either goes underneath the ball or out to the side of the ball," he said. "To throw an effective pitch of any kind, your fingers have to stay on top of the ball. So you go back and make sure that this stays closed and this stays closed" -- he touched his left shoulder and his left hip -- "and this hand comes up here." The pitching hand was back and above his head. "It's so easy to get to here, in the middle of the windup, and then slide off horizontally with your left side. What you're trying to do instead -- what's right -- is to drive this lead shoulder down during the delivery of the ball. That way, the pitching shoulder comes up -- it has to go up. You've increased the arc, and your fingers are on top of the ball, where they belong."

I said I'd heard pitching coaches urging their pupils to drive the lead shoulder toward the catcher during the delivery.

"Sure, but that's earlier," Tom said. He was all concentration, caught up in his craft. "That's staying closed on your forward motion, before you drive down. No -- with almost every pitcher, the fundamentals are the same. Look at Steve Carlton, look at Nolan Ryan, look at me, and you'll see this closed, this closed, this closed. You'll see this shoulder drive down and this one come up, and you'll see the hand on top of the ball. You'll see some flexibility in the landing leg. There are some individual variables, but almost every pitcher with any longevity has all that-- and we're talking now about pitchers with more than four thousand innings behind them and with virtually no arm troubles along the way."

Someone mentioned Jerry Koosman, who had gone along from the White Sox to the Phillies over the winter, and Seaver reminded us that he and Koosman and Tug McGraw and Nolan Ryan had been together on the 1969 World Champion Mets and that they were all still pitching in the majors, fifteen years later ....

There are other ways to pitch and pitch well, to be sure, Seaver said, and he mentioned Don Sutton as an example. "Sutton's exceptionally stiff-legged," he said, "but he compensates because he follows through. He doesn't do this." He snapped his right arm upward in a whiplike motion after releasing an imaginary ball. "The danger with a stiff front leg is recoiling."

...."What is the theory of pitching?" he went on. He sounded like a young college history lecturer reaching his peroration. "All you're doing is trying to throw a ball from here to here." He pointed off toward some plate behind us. "There's no energy in the ball. It's inert, and you're supplying every ounce of energy you can to it. But the energy can't all go there. You can't do that -- that's physics. Where does the rest of it go? It has to be absorbed back into your body. So you have to decide if you want it absorbed back into the smaller muscles of the arm or into the bigger muscles of the lower half of your body. The answer is simple. With a stiff front leg, everything comes back in this way, back up into the arm, unless you follow through and let that hand go on down after the pitch."

But isn't that leg kick -- " I began.

"The great misnomer in pitching is the 'leg kick,'" he interrupted. "That's totally wrong. Any real leg kick is incorrect. Anytime you kick out your leg you're throwing your shoulders back, and then you're way behind with everything. You've got to stay up on top of this left leg, with your weight right over it. So what is it, really? If it isn't a leg kick, it's a knee lift! Sure, you should bend your back when you're going forward, but -- " He stopped and half-shrugged, suddenly smiling at himself for so much intensity. "I give up," he said. "It's too much for one man to do. It's too much even to remember." He laughed -- his famous giggle -- and went off for his shower.

-- Roger Angell

Game Time: A Baseball Companion

2nd INNING

The Knothole Gang and Ladies' Day

For many years it was the custom of owners to set aside certain days on which school children or orphanage youngsters were admitted free. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle held an Honor Roll Contest for Brooklyn public school children in 1914, with an anticipated 15,000 winners to be awarded free admission to Ebbets Field. In 1906 the Giants advertised with a parade from Union Square to the Battery, in which more than 2,000 boys wearing their baseball uniforms marched with the Giants and visiting Cincinnati players riding in front. One year more than two hundred amateur teams marched in review past the Giants and Pirates at the Polo Grounds ....

Most active in this program for creating future fans were the Cardinals, who inaugurated their "knothole gang" in St. Louis in 1917. The program was originally conceived by a group of St. Louis businessmen as part of a scheme for bailing the club out of financial difficulty through a public offering of Cardinal stock. Purchase of two shares at $25 each entitled the buyer to a season pass for a St. Louis youngster. Much was made of the opportunity to combat juvenile delinquency, which the plan supposedly offered. Those who could afford to invest in baseball stock, however, were not acquainted with poor boys, so eventually the free admissions were handled by the club, which channeled them through such local organizations as the Boy Scouts, the Y.M.C.A., Protestant Sunday schools, Catholic churches, Jewish welfare, and a Negro boys' club. Under the program nearly 64,000 boys were admitted free in the 1920 season. League President Tener declared that the plan created a higher standard of sportsmanship among youthful fans, and he urged other National League teams to adopt the idea. So well did the youngsters learn their lessons in sportsmanship that they took up the cry of "Robber!" when the umpire called a decision against the home team, until Branch Rickey, club president, warned that further demonstrations would mean suspension of free passes ....

National League teams did not rush to adopt the "knothole gang" innovation. Certainly the Brooklyn club of the 1920s made no real effort to stimulate youthful interest. And in those days before the affluent society, few boys had fifty cents to spend for a bleacher seat. But there were ways to see games at Ebbets Field without paying. A boy could earn a pass to the bleachers by picking up trash in the stands the morning of a game, or he could work on a turnstile, for which he got fifty cents and a chance to see the game after the fifth inning. Such opportunities were available to a few interested youngsters at a time when operation of a ball club was far simpler and more informal than it later became. If a boy was not chosen for one of these jobs, he had other means of seeing a game free, provided he was resourceful and lucky. He might stand near the gate pass on Cedar Place on the chance that somebody would have an extra pass. He could pry up an unused side gate ... so that he could squirm underneath. Or he could slip into the park in the early morning when several gates were opened to take in supplies and then hide there until it was safe to mingle with the crowd. But hours of patient waiting in hiding might end in discovery by the special police and a rough ejection from the park.

Ladies' Day, a weekday on which women escorted by men were admitted free, was a promotion stunt as old as baseball itself. But some owners had misgivings about the practice, believing that the ladies were getting too accustomed to free admission and, in any case, women had developed enough interest in baseball to be willing to pay their own way, so why forego this source of income? The National League abolished Ladies' Day in 1909. However, there were sporadic attempts by a few clubs to revive it, and some American League teams kept it on. After 1917 the Ladies' Day idea regained momentum and became established in St. Louis, Chicago, and Cincinnati, even to the point where women were admitted without an escort.

-- Harold Seymour

Baseball: The Golden Age

3rd INNING

From the Editor: The 2006 Super Team

Call it the 2006 That's Baseball Super Team -- my picks for the best players (by position) of the season. I'm not waiting until after the Fall Classic because not much stock is put in post-season performance; it's the consistent superior performance through the day-to-day grind of the regular season that impresses me most.

CATCHER: Ivan Rodriguez (DET) or Joe Mauer (MIN)?

Mauer is the real deal. He hit .308/6/17 in 35 games and had a .991 fielding pct. in 32 games in his rookie year (2004). There was no sophomore slump for Mauer in '05, which he finished .294/9/55 with a .993 fielding pct. (5 errors) in 116 games. This year he won the NL batting title with a .347 average, 13 homers and 84 ribbies, and a fielding pct. of .996 (4 errors) in 120 games. But has he been in Minnesota long enough to establish the kind of leadership quality that Ivan Rodriguez demonstrated in his 12 years with the Texas Rangers and the last three seasons with Detroit? Offensively, Pudge Rodriguez finished the regular season with marks of .300/13/69. His career BA is .304 with 277 home runs and 1119 RBI. There is no sign that he is slacking off the pace in this, his 16th, season. As backstop this season he committed just 2 errors in123 games for a .998 fielding pct. His career fielding pct. is .991. He is a 13-time All-Star (including this season), 11-time Gold Glove recipient, 7-time Silver Slugger. His passion for the game remains high, and the work he has done with Detroit's very young and very talented pitching staff is exemplary. I expect Mauer to make this Super Team in the near future, but this year I have to go with IVAN RODRIGUEZ.

FIRST BASE: Ryan Howard (PHI), Albert Pujols (STL), Mark Texeira (TEX) or Justin Morneau (MIN)?

In just his third year in the majors Howard has shown that he is a force to be reckoned with, finishing the year with a .313 BA, 58 home runs and 149 RBI. He committed 14 errors in 1412 innings (159 games) for a .991 fielding pct. Last year he was named the NL's Rookie of the Year and this season he made the All-Star team for the first time. It certainly won't be the last. Pujols hit at a .331 clip in '06, clubbing 49 homers and 137 RBI. He'd have added to those last two stats but for a long stint on the DL. He committed just six errors in 1244.1 innings for a .996 FP. Of course, Prince Albert was an All-Star this year, as he has been every year he's been in the league save for 2002. Among other things, he was the NL-MVP in 2001, and the NL-MVP in 2005. No Gold Gloves yet, but the competition is stiff, and his prowess at the plate overshadows his excellent glovework. Morneau finished the season with .321/34/130 and his fielding percentage is .994, with just 8 miscues in 1346.1 innings. Texeira has the best FP of them all -- .997 with only four errors in 1399 innings. He hit .282 with 33 homers and 110 ribbies. But the sheer power of Howard and Pujols overshadows the others. Like Joe Mauer, Howard waits in the wings, as this year's Super Team first-sacker is ALBERT PUJOLS.

SECOND BASE: Robinson Cano (NYY), Placido Polanco (DET) or Orlando Hudson (ARI)?

Pujols would like to have his best friend, Placido Polanco, join him on the Super Team. Polanco hit .295/4/52 this year and has career marks (9 seasons) of .300/63/382. He seldom makes mistakes, with just six miscues in 943 innings (108 games) for a .989 FP, just a tad off his .991 career pct. at second. He plays shortstop and third base just about as well. Oddly, he's never gotten the nod for a Gold Glove or an All-Star berth. Cano is the young phenom of that star-studded Yankee cast, hitting .342 this year with 15 roundtrippers and 78 RBI, making the All-Star roster in this, his second, season. He was charged with nine errors in 1009 innings for a .984 fielding percentage. Cano will be wearing the pinstripes long after Giambi and Matsuki and even Jeter are gone, or the entire Yankee front office belongs in a lunatic asylum. Orlando Hudson hit .287/15/67 in 579 ABs (157 games). He committed 13 errors in 1349 innings for a .984 FP. O'Dog won a Gold Glove last year (6 errors, 1067.2 innings, .991 FP). Polanco is a complete player, O-Dog is one of my favorites, but the Super Team second baseman has to be ROBINSON CANO.

THIRD BASE: Joe Crede (CHW), Ryan Zimmerman (WSN) or Freddy Sanchez (PIT)?

Scott Rolen and Chipper Jones are hitters to be feared but have too many miscues this year (15 in 1215.2 innings and 18 in 888.1 innings, respectively). The candidates for the hot corner are clearly a trio of young guns. Crede had his best year yet in the batter's box, with marks of .283/30/94. He committed just 10 errors in 1260 innings (.978 FP). Zimmerman had a.287 BA with 20 homers and 110 RBI for the Nationals. (He hit six more doubles, one more triple and struck out 40 less times than teammate Alfonso Soriano.) He made 15 mistakes in 1368.1 innings for a .965 FP as the regular third baseman (for the first time in his career). Sanchez hit .344 with 6 homers and 85 RBI, winning the NL batting title and going to his first All-Star game. He played 99 games at third, committing six errors for a .981 FP in 821.2 innings. These ballplayers are noted for their amazing fielding exploits, and will set the standard at their position for years to come. But this year we have to give the Super Team third baseman slot to FREDDY SANCHEZ.

SHORTSTOP: Michael Young (TEX), Derek Jeter (NYY), Miguel Tejada (BAL)

Playing for the Rangers means Young tends to be overlooked, but he finished 2006 with a .314 BA, 14 home runs and 103 RBI. His fielding percentage of .981 was the result of 14 errors in 1356.1 innings. As in the previous two seasons, he was an All-Star in '06. Tejada committed 19 errors in 1293.2 innings for a .972 FP, right in line with his .971 career mark. He batted .330 with 24 homers and 100 RBI, better than last season but still off what was probably his career year in '04 -- .311/34/150. Tejada was named an All-Star this year, the fourth time in his career. Jeter was charged with 15 miscues in 1292.1 innings for a .975 FP, hit .343/14/97, was named an All-Star for the eighth time in a 12-year career, will probably win his third consecutive Gold Glove, and may well be named AL-MVP. Then there are the intangibles; on a team of superstars Jeter shines the brightest. He is the captain, the leader. Young is very deserving, but the Super Team shortstop is DEREK JETER.

LEFT FIELD: Carl Crawford (TBD) or Eric Byrnes (ARI)?

Crawford was an All-Star in 2004. Why he wasn't this year is a mystery. In '06 he hit .305 with 18 homers and 77 RBI, his best season at the plate. He committed three errors in 1252.1 innings for a .990 FP. I guess you could call this is an off-year for Crawford defensively, since he had a .994 FP last year and a .996 FP in '04 (in left field). Crawford brings an added dimension -- he is one of the premier base stealers in the majors, leading the AL (for the third time in four seasons) with 58 this year. (He also leads the junior circuit in triples -- 16 -- for the third year in a row.) Eric Byrnes was charged with just one error in 1051 innings this year. He ought to be a frontrunner for the Gold Glove. At the plate he hit .267 with 26 homers and 79 RBI, and stole 25 bases to boot. It's close, but the Super Team leftfielder is CARL CRAWFORD.

CENTER FIELD: Andruw Jones (ATL), Carlos Beltran (NYM), Grady Sizemore (CLE) or Torii Hunter (MIN)?

Perennial All-Star and Gold Glove recipient Andruw Jones made just two errors in 1317.1 innings this year, so expect to see him add another Gold Glove Award to his resume. He hit .262/41/129, which is consistent with his previous seasons in the batter's box. Beltran, the 1999 Al_ROY, has been an All-Star for three consecutive years, hit .275/41/116 and committed two errors in 1184 innings in center field, his best year with the glove. You could have mistaken him for Andruw Jones. Sizemore was a first-time All-Star in this, his third, season. He was charged with three errors in 1379.1 innings. He batted .290, hitting 28 long balls and collecting 76 RBI. He also stole 22 bases -- but struck out a whopping 153 times. Hunter has won Gold Gloves every year since 2001 and this year had four errors in 1232.1 innings for a .989 FP, right in line with his career numbers. He was .278/31/98 at the plate. Jones would probably have made the Super Team last year, Sizemore may well make it next year, and Hunter was great but not quite great enough, as this year the center fielder of choice is CARLOS BELTRAN.

RIGHT FIELD: Bobby Abreu (NYY), Brad Hawpe (COL) or Jermaine Dye (CHW)?

Abreu was an All-Star in '04 and '05 but didn't make the squad this year. He hit just 15 homers (his fewest since 1997),with 107 RBI and a .297 BA. Defensively he was, as usual, nearly flawless, with three errors in 1293 innings and a .990 fielding percentage. He won the Gold Glove last year and probably will this year, too. Whatever they were doing with the humidor at Coors Field this year didn't seem to faze Hawpe, who had a banner year at the plate -- .293/22/84. He committed four errors in 1197.2 innings in right field for a .987 FP. Hawpe tends to be overlooked because of the club he's with, but it will be hard to ignore him if he keeps this up in the years to come. Dye was an All-Star this year, the World Series MVP last year, and a Gold Glover in 2000 when he committed 7 errors for a .976 FP. This year he was charged with 6 miscues and ended up with a fielding pct. of .981, while hitting .315/44/120, better marks even than last year's. Clearly, the best choice for the Super Team in right field is JERMAINE DYE.

STARTING PITCHER: Johan Santana (MIN), Justin Verlander (DET),Aaron Harang (CIN) or Francisco Liriano (MIN)?

Santana, who won the Cy Young Award in 2004, was an All-Star this year as well as last. He finished the season 19-6 with a 2.77 ERA. He led the AL in WHIP, strikeouts (245), wins, and a host of other categories. Rookie Verlander was 17-9 in the 2006 regular season and finished up with a 3.63 ERA. Harang (16-11, 3.76 ERA) led the NL in wins, strikeouts (216) and complete games (6). Liriano, a 2006 All-Star was 12-3 with a 2.16 ERA but pitched just 121.0 innings. Who knows what might have been if he'd had a whole season on the mound. (He didn't join the rotation until May 19 and missed a lot of time with arm ailments.) There's not much to debate here -- the best choice for the Super Team's starter is southpaw JOHAN SANTANA.

RELIEF PITCHER: Trevor Hoffman (SDG), Francisco Rodriguez (LAA) or Jonathan Papelbon (BOS)?

Hoffman surpassed Lee Smith as the all-time leader in saves this season. He led the NL in saves (46) and was named to the All-Star squad for the fifth time in his 14-year career. He finished with a 2.14 ERA in 63 IP, which is impressive -- until compared to Jonathan Papelbon's 0.95 mark in 68.1 innings. In the process Papelbon collected 35 saves. Papelbon also made it to the All-Star Game. Rodriguez was an All-Star two years ago but was passed over this season, even though he led the AL with 47 saves. He finished with a 1.73 ERA in 73 IP. Papelbon served up 40 hits, seven earned runs, 13 walks and three dingers while fanning 75 (68.1 IP); Rodriguez allowed 52 hits, 14 ER, 28 walks and 6 homers while striking out 98 (73.0 IP). Hoffman gave up 48 hits, 15 ER, 13 walks and six homers, collecting 50 K (63.0 IP). It's a tough call, but this year's Super Team reliever is JONATHAN PAPELBON.

The players selected are awarded the right to say -- in the distant future when they're in the twilight of their careers and passing the time with other oldtimers swapping stories and bragging about the highlights of their time in the game -- "Oh, yeah? Well, I was elected to the 9 Innings Super Team of '06." It's something no one will ever be able to take away from them.

-- J. Manning

4th INNING

In the News: Goodbye, Tiger Stadium

Former outfielder Willie Horton, a baseball legend in Motown, avoids driving anywhere close to Tiger Stadium. Baseball hasn't been played there for seven years, but seeing the ballpark is too emotional for Horton.

....A new era of Detroit championship baseball begins Saturday night when the Tigers play Game 1 of the World Series in their snazzy $300 million Comerica Park. Opened in 2000, Comerica has roomy concourses, carnival rides, a downtown view, giant tiger sculptures and an outfield fountain that sprays water synchronized to music.

The park is just over a mile from the corner of Michigan and Trumbull, where decaying Tiger Stadium sits waiting to be demolished. The no-frills park that opened in 1912 (as Navin Field), hosted 12 World Series games and averaged 1.6 million fans a year since 1960 is an albatross in the area's economic growth, officials say.

After seven years of intense debate, city elders announced plans in June to raze the park next year and build retail stores, apartments and condominiums, a museum and a baseball field where children 12 and younger can step into the same batter's box as Ty Cobb, Hank Greenberg and Al Kaline .... The field will stay the same, and developers will keep as much of the ballpark as possible.

...."The city has been criticized for not having done anything but ... we spent time finding the right use and we wound up with something no other city has -- youth baseball players on a former major league diamond[," says Peter Zeiler, special projects manager for the Detroit Economic Growth Corp.]

Not everyone agrees. Most who don't are clinging to the tradition of baseball in that Corktown area.

Tiger Stadium, site of three All-Star Games (two as Briggs Stadium), is the symbol of the club's glory years, especially when the most recent Tigers were losing. (This season they had their first winning record since 1993.)

Louis Beer of Clarkston, Mich., is the leader of the Navin Field Consortium, a group that proposed returning the ballpark to its original 1912 configuration when it had 18,000 seats. Beer wanted to bring in an independent or minor league team."

....Some former Tigers think it is time for the ballpark to go. "I don't understand the people who want to keep the ballpark because it is an eyesore," says Jack Morris, who won 198 games for the Tigers from 1977-90.

Hall of Famer Kaline agrees: "It was a great old ballpark for the fans to watch a game, but there was nothing else good about it."

....Horton ... was the youngest of 21 children growing up in the Jeffries Projects 10 minutes from Tiger Stadium .... As a kid, [he] and his friends used the Tiger Stadium walls as a backstop to play baseball. He would sneak into the stadium with concession trucks, hide in Dumpsters and go into the park when the gates opened.

At 17, Horton came to Tiger Stadium and signed his first contract. He hit a home run in his first game there, off the Baltimore Orioles' Robin Roberts. There is a statue of Horton outside Comerica Park, and his uniform No. 23 has been retired.

He speaks of throwing out the Cardinals' Lou Brock at home plate in the 1968 World Series, about the '72 playoffs and how Tiger Stadium was so intimate that teammate Gates Brown's dad, John, could give him batting tips as he stood in the on-deck circle.

Horton thumps his chest and says, "Tiger Stadium will always be branded right here. There's not a day goes by that I don't think of Tiger Stadium. We played more than a game there. That's where I learned about life."

-- Mel Antonen

USA Today (10.19.06)

5th INNING

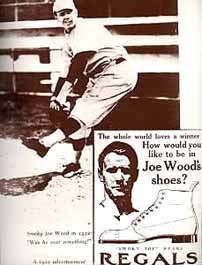

Joe Wood: My Greatest Season

It was ... 1907 that I really started in organized ball, with Hutchinson in the Western Association .... I had a pretty good year there, won about 20 games and struck out over 200 men, and after the 1907 season was over I was sold to Kansas City in the American Association. I pitched there until the middle of the 1908 season, when John I. Taylor bought me for the Boston Red Sox and I reported ... that August. It was ... 1907 that I really started in organized ball, with Hutchinson in the Western Association .... I had a pretty good year there, won about 20 games and struck out over 200 men, and after the 1907 season was over I was sold to Kansas City in the American Association. I pitched there until the middle of the 1908 season, when John I. Taylor bought me for the Boston Red Sox and I reported ... that August. Rube Marquard came up to the Giants from Indianapolis a month later. We'd pitched against each other many and many a time when he was with Indianapolis and I was with Kansas City .... Neither one of us was nineteen years old yet .... Four years later we faced each other again in the 1912 World Series, and then again eight years after that in the 1920 World Series ....

Of course, that Red Sox team I joined in 1908 turned out to become one of the best teams of all time. Tris Speaker had been on the club earlier that year but had been farmed out to Little Rock, where he hit .350 and led the league. He came back up a few weeks after I got there and we started to room together, and we roomed together for 15 years, first with the Red Sox and later with Cleveland ....

There was nobody even close to that man as an outfielder, except maybe Harry Hooper. Speaker played a real shallow center field and he had that terrific instinct -- at the crack of the bat he'd be off with his back to the infield, and then he'd turn and glance over his shoulder at the last minute and catch the ball so easy it looked like there was nothing to it ....

Harry Hooper joined the Red Sox the next year. He was the closest I ever saw to Speaker as a fielder. It's a real shame Harry was on the same club as Spoke, having to play all those years in his shadow. Just like Gehrig with Ruth, or Crawford with Cobb.

Won 11 games for the Red Sox in 1909, 12 in 1910, and then 23 (including a no-hitter) in 1911 and 34 in 1912. That was my greatest season, 1912: 34 wins, 16 in a row, 3 more in the World Series, and, of course, beating Walter Johnson 1-0 in that big game at Fenway Park on September 6, 1912.

....The newspapers publicized us like prizefighters: giving statistics comparing our height, weight, biceps, triceps, arm span, and whatnot. The Champion, Walter Johnson, versus the Challenger, Joe Wood. That was the only game I ever remember in Fenway Park, or anywhere else for that matter, where the fans were sitting practically along the first-base and third-base lines. Instead of sitting back where the bench usually is, we were sitting on chairs right up against the foul lines, and the fans were right behind us. The overflow had been packed between the grandstand and the foul lines, as well as out in the outfield behind ropes. Fenway Park must have contained twice as many people as its seating capacity that day ....

Well, I won, 1-0, but don't let that fool you. In my opinion the greatest pitcher who ever lived was Walter Johnson. If he'd ever had a good ball club behind him what records he would have set!

You know, I got an even bigger thrill out of winning three games in the World Series that fall. Especially the first game, when we beat the Giants, 4-3. In the last of the ninth they got Chief Meyers on second base and Buck Herzog on third with only one out, and I started to get a little nervous .... But I struck out both Art Fletcher and Otis Crandall and we won it. They say that was the first time Crandall ever struck out at the Polo Grounds. I fanned him with a fastball over the outside corner. I doubt if he ever saw it, even though he swung at it. The count was three and two and that pitch was one of the fastest balls I ever threw in my life.

That was the Series we won in the tenth inning of the last game. In that last game you always hear about [Fred] Snodgrass dropping that fly ball, but you never hear about the incredible catch that Harry Hooper made in the fifth inning that saved the game for us. That was the thing that really took the heart out of the Giants. Larry Doyle hit a terrific drive to deep right center, and Harry ran back at full speed and dove over the railing and into the crowd and in some way, I'll never figure out quite how, he caught the ball -- I think with his bare hand. It was almost impossible to believe even when you saw it.

....So there I was after the 1912 season -- including the World Series I'd won 37 games and lost only 6, struck out 279 men in days when the boys didn't strike out much, and I'd beaten Walter Johnson and Christy Mathewson one after the other. And do you know how old I was? Well, I was twenty-two years old, that's all. The brightest future ahead of me that anybody could imagine in their wildest dream.

And do you know something else? That was it. That was it, right then and there. My arm went bad the next year and all my dreams came tumbling down around my ears like a damn house of cards. The next five years, seems like it was nothing but one long terrible nightmare.

-- Lawrence S. Ritter

The Glory of Their Times

6th INNING

Stats: Brothers

Top Ten Brothers, Career Hits: Paul and Lloyd Waner (5611) ... Felipe, Matty and Jesus Alou (5094) ... Joe, Dom and Vince DiMaggio (4853) ... Ed, Jim, Frank, Joe and Tom Delahanty (4217) ... Hank and Tommie Aaron (3987) ... Cal and Billy Ripken (3857) ... Joe and Luke Sewell (3619) ... Ken, Clete and Cloyd Boyer (3559) ... Honus and Butts Wagner (3474) ... Bob and Roy Johnson (3343)

With 350 Career Home Runs: Hank and Tommie Aaron (788) ... Joe, Vince and Dom DiMaggio (573) ... Eddie and Rich Murray (505) ... Jose and Ozzie Canseco (462) ... Cal and Billy Ripken (451) ... Lee and Carlos May (444) ... Ken, Clete and Cloyd Boyer (444) ... Craig and Jim Nettles (406) ... Dick, Hank and Ron Allen (358)

With 1,800 or More Career Runs: Joe, Dom and Vince DiMaggio (2927) ... Paul and Lloyd Waner (2828) ... Ed, Jim, Frank, Joe and Tom Delahanty (2309) ... Hank and Tommie Aaron (2276) ... Felipe, Matty and Jesus Alou (2213) ... Bob and Roy Johnson (1956) ... Cal and Billy Ripken (1934)

With 1,750 or More Career RBIs: Joe, Dom and Vince DiMaggio (2739) ... Hank and Tommie Aaron (2391) ... Ed, Jim, Frank, Joe and Tom Delahanty (2153) ... Eddie and Rich Murray (1924) ... Cal and Billy Ripken (1920) ... Paul and Lloyd Waner (1907) ... Bob and Emil Meusel (1886) ... Bob and Roy Johnson (1839) ... Ken, Clete and Cloyd Boyer (1803) ... Lee and Carlos May (1780)

With 200 or More Career Wins: Phil and Joe Niekro (539) ... Gaylord and Jim Perry (529) ... John, Dad and Walter Clarkson (383) ... Greg and Mike Maddux (346) ... Ramon and Pedro Martinez (301) ... Stan and Harry Coveleski (297) ... Bob and Ken Forsch (282) ... Gus and John Weyhing (260) ... Jesse and Virgil Barnes (214) ... Al and Mark Leiter (210) ... Dizzy and Paul Dean (200)

-- David Nemec

Great Baseball Feats, Facts & Firsts

7th INNING

Year in Review: 1911

It seemed that Fate would frown on the New York Giants in 1911 when the Polo Grounds caught fire on April 14 and was extensively damaged. The orphaned Giants were taken into Highlander Park by the Yankees, but this was hardly an auspicious manner in which to begin a season. Despite the spring mishap, John McGraw's men stayed close to the pace-setting Chicago Cubs during the summer before taking off in August and leaving the pack behind. The Giants' hot streak dated from the time utility man Art Fletcher was given the shortstop job, and Buck Herzog was reacquired from Boston to fill the third base slot. Staying free of injuries, the Giants passed the Cubs on August 24, and wrapped up the pennant with 20 victories in their final 24 games. The injury-plagued Cubs could not match the Giant pace and had to settle for a second-place finish, 7-1/2 games back. Perhaps aiding the Giants most of all down the stretch was moving back into the rebuilt Polo Grounds in September.

The Giants victory could be found in Rube Marquard who, after two years of mediocrity, fulfilled the promise that had prompted McGraw to shell out $11,000 to purchase his contract in 1908. The left-handed hurler developed into the league's top southpaw, winning 24 games and leading the league in strikeouts. He formed a counterpoint to righty Christy Mathewson, giving McGraw the top pitching duo in baseball. Larry Doyle, Art Fletcher and Chief Meyers posted .300 averages for the Giants, and Fred Merkle provided power and run production for the offense.

Honus Wagner took his eighth and last batting crown with a .334 mark, and Wildfire Schulte of Chicago won the home run title with a tremendous total of 31 circuit blasts, the best power mark since 1899. Eight pitchers chalked up 20 victories, with rookie Grover "Pete" Alexander of the Phillies leading the way with 28.

The American League race was a two-team affair as the Philadelphia Athletics and Detroit Tigers ran away from the rest of the field. Philadelphia started slowly, while Detroit began the year as a hot team. The Athletics righted themselves and played winning ball from May on to stay hot on Detroit's tail throughout the summer. Both teams possessed hich octane offenses, but Connie Mack's pitching staff gave the Athletics the edge. Behind ace pitchers Jack Coombs and Eddie Plank, Philadelphia passed the Tigers on August 4, and did not stop until they had the pennant won by 13-1/2 games. The Athletic infield of Stuffy McInnis, Eddie Collins, Jack Barry, and Frank Baker became known as the $100,000 Infield, and a team batting mark of .296 enabled the strong pitching staff to win 101 games.

Ty Cobb and Sam Crawford formed the most feared batting tandem in the league, but mediocre pitching negated their efforts and failed to give Detroit the balance to overhaul the Athletics. Cobb won his fifth consecutive batting title with a career-high .420 mark, although rookie outfielder Joe Jackson of the Cleveland Indians threatened him all the way with a .408 average. -- the highest runner-up average ever recorded in baseball. Philadelphia's Frank Baker led all batters with 11 homers, and teammate Jack Coombs led in wins with 28.

--David S. Neft, Richard M. Cohen, Michael L. Neft

The Sports Encyclopedia: Baseball (22nd ed.)

8th INNING

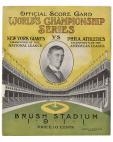

The 1911 World Series

Philadelphia Athletics (4) v New York Giants (2)

October 14-26

Shibe Park (Philadelphia), Brush Stadium (New York)

The Athletics' pitchers continued to handcuff batters in the World Series as they held the Giants to a .175 batting average and 13 runs in a six-game Series won by the Mackmen. Bender, Coombs, and Plank all pitched complete game victories, but the star of the Series was Athletic third baseman Frank Baker. Besides hitting .375t, his home run in the second game beat Rube Marquard, and another homer in the ninth inning of the third game off Christy Mathewson tied the score. The third baseman's power performance was substantial enough to have the press immediately dub him as Home Run Baker -- one

of the early heroes of Series play. (The Sports Encyclopedia: Baseball, Neft, et al.) of the early heroes of Series play. (The Sports Encyclopedia: Baseball, Neft, et al.)Game 1: New York 2, Philadelphia 1

Game 2: Philadelphia 3, New York 1

Game 3: Philadelphia 3, New York 2

Game 4: Philadelphia 4, New York 2

Game 5: New York 4, Philadelphia 3

Game 6: Philadelphia 13, New York 2

PHILADELPHIA: Frank Baker (3b), Jack Barry (ss), Chief Bender (p), Eddie Collins (2b), Jack Coombs (p), Harry Davis (1b), Jack Lapp (c), Bris Lord (of), Stuffy McInnis (1b), Danny Murphy (of), Rube Oldring (of), Eddie Plank (p), Amos Strunk (of), Ira Thomas (c). Mgr: Connie Mack

NEW YORK: Red Ames (p), Beals Becker (ph), Doc Crandall (p), Josh Devore (of), Larry Doyle (2b), Art Fletcher (ss), Buck Herzog (3b), Rube Marquand (p), Christy Mathewson (p), Fred Merkle (1b), Chief Meyers (c), Red Murray (of), Fred Snodgrass (of), Art Wilson (c), Hooks Wiltse (p). Mgr: John McGraw

Six days of heavy rains in Philadelphia caused a week-long gap between Games 3 and 4.

9th INNING 9th INNINGPlayer Profile: Tommy Henrich

Nickname: "Old Reliable"

Born: February 20, 1913 (Massillon, OH)

ML Debut: May 11, 1937

Final Game: October 1, 1950

Bats: Left Throws: Left

6' 0" 180

Played for New York Yankees (1937-1950)

Postseason: 1938 WS, 1941 WS, 1947 WS, 1949 WS

All Star 1942, 1947, 1948, 1949, 1950

Tommy Henrich was a fiercely independent individual who jealously guarded his private life. He made a conscious effort to appear to live as clean and virtuous a life as Babe Ruth led a rowdy and hell-raising one. For Henrich letting his hair down meant having a few drinks, smoking a big black cigar, or organizing his teammates to harmonize "When Irish Eyes Are Smiling," "Take Me Out to the Ball Game," and "Down by the Old Mill Stream" in the shower of the clubhouse after a Yankee victory.

Mostly what Henrich was was serious. He was a bad loser, and he worked hard at becoming a success. He drove his teammates to be successes too, and if he thought another player was taking money out of his pocket by not hustling or by making a stupid mistake, Henrich would lash into him with a biting criticism, causing hard feelings. The young players on the team feared Henrich's tongue-lashing even more than they did [Casey] Stengel's.

Henrich was the living embodiment of Frank Merriwell and Chip Hilton. In a storybook romance he married a nurse who came to visit him in the hospital just to see what "the star" was like. On the field of play he performed Merriwellian game-winning feats. To the press he said things like, "I get a thrill every time I put on my Yankee uniform. It sounds corny, but it's the gospel truth," and it was the gospel truth. A respected, respectful. and patriotic citizen, with all the Christian virtues, Henrich displayed a restraint and moderation and a lack of flair which too often has blurred the memory of his skillful ability to hit a baseball, especially with a runner in scoring position in the late innings.

Mel Allen, the Yankee broadcaster, nicknamed him Old Reliable, and it is this reliability to deliver key hits in crucial situations for which he is best remembered. His lifetime batting average reads .282, a respectable figure, but he was one of the best .282 hitters in the game, and in the outfield he was admired for his guile and intelligence.

Henrich was always considering the wind currents and the position of the sun and the habits of each batter, and he practiced for hours fielding rebounds off the tricky Yankee Stadium fences. His favorite trick was to wait under a fly ball with a speedy runner on first and a slower one at bat, pretending to set himself to catch it. At the last second he would let it drop, trapping the ball and throwing out the speedier runner at second, sometimes getting a double play if an inattentive batter, lulled into believing Henrich was going to catch the ball, did not hustle down to first.

Henrich first signed with the Cleveland Indians in 1934. After performing spectacularly in the minors for three years, but getting bounced from one farm team to another, he was beginning to feel that the Indians were deliberately trying to impede his progress to the majors. Though Cleveland general manager Cy Slapnicka had told him that he had received offers to buy him from a couple of major league clubs, Slapnicka himself kept Henrich from coming to Cleveland, leaving him in the minors. Henrich, an intelligent thinking man, and a force to be reckoned with when angered, daringly wrote to baseball commissioner Judge Landis, asking him to investigate, knowing that if Landis saw no wrongdoing, Cleveland might let him languish in the minors forever. Landis did investigate, and he declared Henrich a free agent. Eight major league teams, including the Yankees, rushed to sign him. The Yankees offered him $25,000, outbidding everyone else. Henrich was sent to Newark, the Yankees' top farm club, where he played one week. In April of 1937 Yankee manager Joe McCarthy became angry with the attitude of outfielder Roy Johnson. After ordering general manager Ed Barrow to "trade, sell, or release Johnson," he told Barrow, "bring up that kid at Newark." Henrich became a Yankee fixture in right field for ten seasons, joining Joe DiMaggio and Charlie Keller to form one of the all-time classic outfield combinations. Despite a three-year Coast Guard hitch during World War II, for eleven seasons Henrich starred for the Yankees. He retired in 1950 because of 27-year-old arthritic knees.

-- Peter Golenbock

Dynasty: The New York Yankees, 1949-1964

EXTRA INNINGS

Baseball Dictionary

Babe Ruth Baseball

Founded in 1951, this nonprofit organization supports summer leagues for youngsters age 9-18.

backdoor slide

An unconventional slide in which the baserunner's body goes past the bag before he touches the bag, normally resorted to when the runner realizes he is in danger of being tagged out.

backdoor slider

A slider that starts outside but slices in over the outside corner of the plate. Also used to describe a slider thrown by a RHP to a left-handed batter that crosses the plate moving away from the batter.

back end

The trailing runner in a double steal.

backhand

Fielding a ball by reaching the glove across the body.

back off

A pitcher is said to "back a batter off" when he throws inside in an effort to move the batter away from the plate.

backstop

(1) A screen behind and extending over the home plate area, designed to protect spectators from foul balls. The backstop must be a minimum of 60 feet away from home plate in the majors. First used: Boston Daily Globe, Mar. 27. 1872. (2) A catcher.

back up

In fielding, to move into a supporting position where one can retrieve a ball if another fielder can't reach it or muffs it. For instance, a pitcher sometimes backs up the third baseman who is about to receive a throw from the outfield, or the ssecond baseman may move over towards the first base line, behind the first baseman, when the latter is about to receive a throw from the catcher.

backup

A player who fills in for a regular. A substitute. First used: DeWitt's Base Ball Guide, 1869.

backup slider

A slider thrown over the middle of the plate when the catcher has set up to one side.

THIS MATERIAL IS REPRODUCED FOR NON-PROFIT EDUCATIONAL AND SCHOLARLY PURPOSES ONLY, WHICH COMPLIES WITH THE DOCTRINE OF FAIR USE AS EXPRESSED IN THE COPYRIGHT ACT OF 19 OCTOBER 1976, EFFECTIVE 1 JANUARY 1978 (TITLE 17 OF THE UNITED STATES CODE, PUBLIC LAW 94-553, 90 STAT. 2541.)

|