9 Innings 9 InningsA Baseball History Reader

J. Manning, Editor

|

Issue # 5: September 12, 2006

Brooklyn and Its Bums ... How Do You Figure? ... The Worst Baseball Team of All Time ... "Take Me Out to the Ball Game" ... Sam Crawford: My Teammate, Ty Cobb ... Dusty's Unforgettable Home Run ... Year in Review: 1904 ... Stats: MVP (NL) ... Player Profile: Bo Belinsky ... They Played the Game

|

"[I]t's our game; that's the chief fact in connection with it: America's game; it has the snap, go, fling of the American atmosphere; it belongs as much to our institutions, fits into them as significantly as our Constitution's laws; is just as important in the sum total of our historic life."

-- Walt Whitman

1st INNING

Brooklyn and Its Bums

There was an informal, nonprofessional quality to Ebbets Field and the Dodgers. It was very personal. The fans loved the players. The players loved the fans. All a player had to do was walk out onto the field, and the fans would begin waving at him and hollering to be waved back at, and they would throw down little vials of holy water and religious medals, and when a ballplayer had a birthday, there would always be one or two homemade cakes in the clubhouse for him.

In Ebbets Field there might be 5,000 fans in the park, but it would sound like ten times as many. Five fanatical fans that made up the Dodgers Symphony would play and dance on top of the dugout and walk through the stands playing their ragtime music, and when the umps came out before the game, they would play "Three Blind Mice," until the year when the National League added a fourth umpire to the crew, lousing up their little joke. If an opposing pitcher was knocked out, the symphony would razz him by playing "The Worms Crawl In, The Worms Crawl Out," and they would wait for an opposing batter who made [an] out to return to the dugout and sit down, and just as the player's backside would touch the bench, the cymbal from the symphony would crash, and the Dodger fans would applaud and chuckle at the player's embarrassment. In Ebbets Field there might be 5,000 fans in the park, but it would sound like ten times as many. Five fanatical fans that made up the Dodgers Symphony would play and dance on top of the dugout and walk through the stands playing their ragtime music, and when the umps came out before the game, they would play "Three Blind Mice," until the year when the National League added a fourth umpire to the crew, lousing up their little joke. If an opposing pitcher was knocked out, the symphony would razz him by playing "The Worms Crawl In, The Worms Crawl Out," and they would wait for an opposing batter who made [an] out to return to the dugout and sit down, and just as the player's backside would touch the bench, the cymbal from the symphony would crash, and the Dodger fans would applaud and chuckle at the player's embarrassment.....Never had there been such involvement .... At Ebbets Field before each game, the fans would line up along the railing, and the players would walk along and shake hands with everybody and sign autographs and chat about that afternoon's game. For many of the fans, the Dodgers became part of their family. And every once in a while, the Dodgers made a fan part of theirs.

IRVING RUDD: "I remember when I was a kid, I used to major in hooky. I would run off to the ballpark at the drop of a hat. And one day .... I was hanging around outside the ballpark, holding my scrapbook under my arm, when Al Lopez came out of the clubhouse. He was a kid catcher, about twenty years old, and he's got with him a guy by the name of Hollis Thurston, who had been a good pitcher with the White Sox, and a guy by the name of Louis 'Buck' Newsom, who was Bobo later, Jake Flowers, and Clise [Dudley] .... Lopez says to me, 'Hey, kid, how 'bout going to dinner with us?' I said, 'Gee, I have to ask my mother.' He said, 'Give her a call.' Who had a phone in those days? .... I told him we didn't have a phone. They asked me where I lived, and I told them, 'Powell Street in Brownsville,' and Lopez said, 'We'll drop you off on the way home. You ask your mother.' And he added, 'Wash your face, too, and put another pair of pants on.' I was a sloppy kid in those days.

"So we got into the car ... and they drove me to Brownsville....

"It was so different then. I remember going up to Dazzy Vance, when he was leaving the ballpark. I said, 'Hey, Daz, that pitch you threw in the ninth inning...' He said, 'Kid, let me tell you about it. Now, you got a guy like Hack Wilson playing against you...' and as we walked, we talked about the game. And that's the way it was then."

....The Dodger fans were part of the show, part of the sights and sounds that made Ebbets Field so special. Some of those fans became almost as renowned as the players they came to watch. The other Dodger fans may not have known their names, but they could count on them being there and adding to the noise and craziness.

....The most famous of the Dodger fans -- perhaps the most famous in baseball history, was named Hilda Chester, a plump, pink-faced woman with a mop of stringy gray hair. Hilda began her thirty-year love affair with the Dodgers in the 1920s. She had been a softball star as a kid, or so she said, and she once told a reporter that her dream was to play in the big leagues or start up a softball league for women. Thwarted as an athlete, she turned to rooting. As a teenager she would stand outside the offices of the Brooklyn Chronicle every day, waiting to hear the Dodger score. After a while she became known to the sportswriters, who sometimes gave her passes to the games. In her twenties Hilda worked as a peanut sacker for the Stevens Brothers ... who owned most of the concession stands across the country .... [I]n her capacity as peanut sacker she was able to work and attend the Dodger games. By the 1930s she was attending games regularly, screaming lustily, one of hundreds of Ebbets Field regulars.

Shortly after suffering a heart attack, she began her rise to fame. Her physician forbade her from yelling, and when she was sufficiently recovered, she returned to Ebbets Field with a frying pan and an iron ladle. Banging away on the frying pan from her seat in the bleachers, she made so much noise that everyone, including the players, noticed her. It was the Dodger players in the late 1930s who presented Hilda Chester with the first of her now-famous brass cowbells.

In 1941 Hilda suffered a second heart attack, and when she entered the hospital this time, she was an important enough personality that Durocher and several of the players went to visit her. As a result Durocher became Hilda's special hero, and by the mid-1940s she was almost the team mascot. Sometimes during short road trips, Hilda even went with the team....

During the games Hilda lived in the bleacher seats with her bell. Durocher had given her a lifetime pass to the grandstand, but she preferred sitting in the bleachers with the entourage of fellow rowdies. With her fish peddler voice, she'd say, "You know me. Hilda wit da bell. Ain't it trillin'? Home wuz never like dis, mac." When disturbed her favorite line was, "Eacha heart out, ya bum!"

Hilda had a voice that could be heard all over the park. It stood out above all the other voices, and the players could hear her raspy call followed by the clanging of her cowbell all through a game.

-- Peter Golenbock

Bums: An Oral History of the Brooklyn Dodgers

2nd INNING

How Do You Figure?

EARNED RUN AVERAGE is calculated by adding up the EARNED RUNS allowed by a pitcher, multiplying that number by nine, and dividing by INNINGS PITCHED. (If a run scores as the result of an error, then it is not considered an "earned" run.) For example, if a pitcher allows two earned runs in six innings of work, his ERA would be 3.00 (2 x 9 divided by 6).

BATTING AVERAGE is calculated by dividing a batter's HITS by his AT BATS. A player has an at-bat if he hits safely, strikes out, or hits into an out. If a player reaches base due to a walk or a hit-by-pitch, he is not considered to have had an "at bat." (However, if a player reaches base due to an error or fielder's choice, he is considered to have had an "at-bat.") For example, if a batter comes to the plate four times, gets a hit, strikes out, walks, and reaches on a fielding error, his batting average is .333, arrived at by dividing one hit by three at-bats (the base on balls is not counted).

FIELDING PERCENTAGE is calculated by adding up a fielder's PUTOUTS and ASSISTS and dividing that number by TOTAL CHANCES. (Total chances is the sum of a player's putouts, assists, and errors combined; an assist is when the fielder throws the ball to a teammate who makes a putout.) A player may field the ball and not get a putout, assist or error -- this is not considered a "chance." A player can also get more than one "chance" on a double- or triple-play.

OBP, or On Base Percentage is a measurement of how often a batter gets to first base for any reason other than a fielding error or fielder's choice. OBP is calculated by adding HITS + BASES ON BALLS + HIT BY PITCH and dividing that number by AT BATS + BASES ON BALLS + HIT BY PITCH + SACRIFICE FLIES.

A batter's SLUGGING PERCENTAGE is determined by dividing TOTAL BASES by official AT BATS. Total bases are all the bases the batter reached when he hit safely (and, so, does not include bases on balls or a base awarded because the batter was hit by a pitch.) An official at-bat, of course, would not be one that resulted in a walk, a sacrifice, or a hit by a pitch.

-- J. Manning

3rd INNING

The Worst Baseball Team of All Time

The Cleveland Spiders of 1899 were certifiably the worst team in baseball history. Wallowing in the basement of the 12-team National League, these laughable losers piled up an amazing 134 losses against only 20 wins for the all-time lowest winning percentage of .130. They finished 84 games out of first, making the rest of history's lousiest teams seem like pennant contenders. The Cleveland Spiders of 1899 were certifiably the worst team in baseball history. Wallowing in the basement of the 12-team National League, these laughable losers piled up an amazing 134 losses against only 20 wins for the all-time lowest winning percentage of .130. They finished 84 games out of first, making the rest of history's lousiest teams seem like pennant contenders.The Spiders were last in runs, doubles, triples, homers, batting average, slugging percentage, and stolen bases. They were outscored by a two-to-one margin, 1,252 runs to 529. Appropriately enough, the Spiders lost the first game of the season 10-1 to start their losing habit. Six different times they recorded losing streaks of eleven or more games. Once, in Brooklyn, they found themselves in an unfamiliar situation -- leading 10-1 after six innings. Refusing to bow to victory, they managed to pull out the defeat by an 11-10 score.

With losses piling up left and right, manager Lave Cross quit in disgust before the end of the first month. Blame the team's abysmal record on the owners, brothers Frank and Matthew Robison, who knew little about baseball. Rather than hire more talent before the season started, they bought a second team, the St. Louis Browns, and then set about dissecting the Spiders. To guarantee failure of the Spiders, the Brothers Robison shipped their best players, including Cy Young, to the Browns. Young won 26 games for St. Louis that season -- six more than his former team won all year .... The two aces on the [Spiders] staff, Charlie Knepper and Jim Hughey, each won a paltry four games and together were responsible for 52 losses.

The Spiders were so bad that even their own loved ones wouldn't come out to watch them. As a result, they played only 41 games of the 154-game schedule in Cleveland .... Fittingly, the Spiders ended their season by dropping 40 of their last 41 games. In their final game they recruited a hotel cigar counter clerk to pitch for them against the Cincinnati Reds. In true Spider tradition, he lost 19-3.

The following year, the league voted to reduce the number of teams, and to no one's surprise, the Spiders were stomped out of existence.

-- Bruce Nash & Allan Zullo

The Baseball Hall of Shame

IMAGE: The Cleveland Spiders of 1898.

4th INNING

"Take Me Out to the Ball Game"

Katie Casey was base ball mad. Katie Casey was base ball mad.Had the fever and had it bad;

Just to root for the home town crew,

Ev'ry sou Katie blew.

On a Saturday, her young beau

Called to see if she'd like to go,

To see a show but Miss Kate said,

"No, I'll tell you what you can do."

"Take me out to the ball game,

Take me out with the crowd.

Buy me some peanuts and cracker jack,

I don't care if I never get back,

Let me root, root, root for the home team,

If they don't win it's a shame.

For it's one, two, three strikes, you're out,

At the old ball game."

Katie Casey saw all the games,

Knew the players by their first names;

Told the umpire he was wrong,

All along good and strong.

When the score was just two to two,

Katie Casey knew what to do,

Just to cheer up the boys she knew,

She made the gang sing this song:

"Take me out to the ball game,

Take me out with the crowd.

Buy me some peanuts and cracker jack,

I don't care if I never get back,

Let me root, root, root for the home team,

If they don't win it's a shame.

For it's one, two, three strikes, your out,

At the old ball game."

Author: Jay Norworth

Composer: Albert Von Tilzer

Published: 1908, 1927

York Music Company

Norworth was a successful entertainer and songwriter ("Shine on, Harvest Moon") when he wrote this classic on a subway train bound for Manhattan. He was reputedly inspired by a sign that read "Ballgame Today at the Polo Grounds." It took Norworth fifteen minutes to write the lyrics. (Von Tilzer then put the words to music.) It was performed by Norworth's wife, Nora Bayes, at the Ziegfried Follies and, by 1910, was a staple at all big league ballparks. It's said that only "The Star Spangled Banner" and "Happy Birthday" are sung more often than "Take Me Out to the Ball Game."

Neither Norworth nor Von Tilzer had ever actually seen a baseball game before creating the song.

5th INNING 5th INNINGSam Crawford: My Teammate, Ty Cobb

Cobb ... was terrific, no doubt about it. After all, he stole almost 900 bases and had a batting average of of .367 over 24 years in the Big Leagues. You can't knock that. I remember one year I hit .378 -- in 1911, it was -- and I didn't come anywhere close to leading the league: Joe Jackson hit .408 and Cobb hit .420. I mean, that's mighty rugged competition!

I played in the same outfield with Cobb for 13 years, from 1905 through 1917. I was usually in right, Cobb in center, and Davy Jones and then Bobby Veach in left. Davy Jones, he was the best lead-off man in the league .... The lineup usually was Davy Jones, Donie Bush, Cobb, and Crawford, although sometimes I batted third and Cobb fourth. That Donie Bush was a superb shortstop, absolutely superb. I think he still holds a lot of records for assists and putouts.

They always talk about Cobb playing dirty, trying to spike guys and all. Cobb never tried to spike anybody. The base line belongs to the runner. If the infielders get in the way, that's their lookout. Infielders are supposed to watch out and take care of themselves. In those days, if they got in the way and got nicked they'd never say anything. They'd just take a chew of tobacco out of their mouth, slap it on the spike wound, wrap a handkerchief around it, and go right on playing. Never thought any more about it.

We had a trainer, but all he ever did was give you a rubdown with something we called "Go Fast." He'd take a jar of Vaseline and a bottle of Tabasco sauce -- you know how hot that is -- mix them together, and rub you down with that. Boy, it made you feel like you were on fire! That would really start you sweating. Now they have medical doctors and whirlpool baths and who knows what else.

But Ty was dynamite on the base paths. He really was. Talk about strategy and playing with your head, that was Cobb all the way. It wasn't that he was so fast on his feet, although he was fast enough. There were others who were faster, though, like Clyde Milan, for instance. It was that Cobb was so fast in his thinking. He didn't outhit the opposition and he didn't outrun them. He outthought them!

A lot of times Cobb would be on third base and I'd draw a base on balls, and as I started to go down to first I'd sort of half glance at Cobb, at third. He'd make a slight move that told me he wanted me to keep going -- not to stop at first, but to keep on going to second. Well, I'd trot two-thirds of the way to first and then suddenly, without warning, I'd speed up and go across first as fast as I could and tear out for second. He's on third, see. They're watching him, and suddenly there I go, and they don't know what the devil to do.

If they try to stop me, Cobb'll take off for home. Sometimes they'd catch him, and sometimes they'd catch me, and sometimes they wouldn't get either of us. But most of the time they were too paralyzed to do anything, and I'd wind up at second on a base on balls ....

Cobb was a great ballplayer, no doubt about it. But he sure wasn't easy to get along with. He wasn't a friendly, good-natured guy, like [Honus] Wagner was, or Walter Johnson, or Babe Ruth .... He wrote an autobiography, you know, and he spends a lot of time in there telling how terrible he was treated when he first came up to Detroit, as a rookie, in 1905. About how we weren't fair to him, and how we tried to "get" him.

But you have to look at the other side, too .... Every rookie gets a little hazing, but most of them just take it and laugh. Cobb took it the wrong way. He came up with an antagonistic attitude, which in his mind turned any little razzing into a life-or-death struggle. He always figured everybody was ganging up against him .... Well, who knows, maybe if he hadn't had that persecution complex he never would have been the great ballplayer he was. He was always trying to prove he was the best, on the field and off. And maybe he was, at that.

-- Sam Crawford

The Glory of Their Times (Ritter)

6th INNING

Dusty's Unforgettable Home Run

Before Dodger Kirk Gibson beat the Athletics in Game One of the 1988 World Series, Dusty Rhodes was the only man in baseball history to grab a bat, pinch-hit in the bottom of the ninth inning or later of a World Series game, and clout a game-winning home run. The day after Gibson's blast against Oakland reliever Dennis Eckersley, Rhodes could tell Gibson what to expect for the rest of his life. Before Dodger Kirk Gibson beat the Athletics in Game One of the 1988 World Series, Dusty Rhodes was the only man in baseball history to grab a bat, pinch-hit in the bottom of the ninth inning or later of a World Series game, and clout a game-winning home run. The day after Gibson's blast against Oakland reliever Dennis Eckersley, Rhodes could tell Gibson what to expect for the rest of his life."They will never, ever let him forget that," said Rhodes, the former Giants outfielder, then age sixty-one and working a tugboat in New York harbor. "Never in a hundred years. Never, ever, ever. No matter how many times he strikes out, all they'll remember is that home run."

Rhodes's unforgettable home run came in Game One of the 1954 World Series. In the eighth inning, Willie Mays had made his astonishing over-the-shoulder catch of Vic Wertz's 460-foot blast to center field. In the bottom of the tenth, New York and Cleveland were still tied 2-2, with Giants on first and second, and one out.

Rhodes was sitting on the bench, steaming at manager Leo Durocher. "I was still kind of mad at the time," drawled Rhodes, Alabama accent intact despite thirty-five years in New York. "Last game of the season in Philadelphia, Leo said, 'The starting lineup tonight is the starting lineup in the World Series.' I played that night.

"So next day is an off-day, and we're working out at the Polo Grounds. I'm hitting in the cage, with all the newsmen around. They said, 'Starting lineup come here for pictures.' I said, 'I'll be with you in a minute.' They said, 'Stay where you are, you ain't playing.' Next day during the game, I was still fuming."

In the tenth inning ... Durocher told him to pinch-hit for Monte Irvin against Indians righty Bob Lemon.

"My intention was to take the first pitch," said Rhodes. "But he hung me a curve. It looked like a balloon up there. So I took a swing and the wind caught it."

It plopped into the short right-field stands at the Polo Grounds and into baseball history. "I can still see Dave Pope jumping for it out there," said Rhodes. "Wertz hit one 460 feet, and Mays caught it. I hit one 250 feet, and I'm a hero for forty years. I turned around and looked at Bob Lemon, and he'd thrown his glove into the stands. It went further than my home run did."

The home run carried Rhodes deep into baseball lore. "I still get three or four letters a week from people looking for me to sign, and they include, 'Congratulations on your home run'," said Rhodes. "I heard Howard Cosell report once it was the cheapest home run ever. I'll tell you one thing: my home run stayed in the air longer than his television show stayed on the air."

Rhodes proceeded to tilt the series from the bench. In Game Two he tied the game with a pinch single, then stayed in the lineup and homered in his next at-bat. In Game Three he pinch-hit and singled with the bases loaded.

"Once in a while when you're down in the dumps, you think about it and it picks you up," said Rhodes.

-- David Cataneo

Baseball Legends and Lore

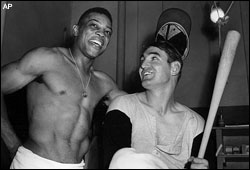

IMAGE: Rhodes (right) celebrates Game One win with Willie Mays in clubhouse.

The New York Giants won the 1954 World Series four games to none.--Ed.

7th INNING

Year in Review: 1904

Seeking to become the first team since the 1885 to 1888 St. Louis Browns to sweep four straight ML pennants, Pittsburgh's dynasty ended with a thud. In 1904, John McGraw's New York Giants devoured the rest of the NL and set a new ML record with 106 victories.

But if McGraw and Giants owner John "Tooth" Brush expected their triumph would captivate New York, they were wrong. The pair faced stiff competition for the hearts of Gothamites from the upstart New York Highlanders, who had joined the AL the previous year. Ironically, McGraw and Brush had paved the way for a rival team in New York when they conspired to kill the Baltimore AL franchise, thinking it would sink the junior circuit. AL president Ban Johnson, however, thwarted their scheme by moving the Maryland team to the Big Apple and outbidding Charlie Comiskey to furnish it with his crafty pitcher-manager, Clark Griffith.

After finishing fourth in 1903, Griffith bagged Jack Powell in a trade to team with his mound ace, Jack Chesbro. The dynamic hill duo posted an AL-record 64 wins by pitching teammates -- 41 of them by Chesbro. For a time it seemed that the pair would catapult the Highlanders to the pennant and force an all-New York World Series. By the final Friday morning of the season, however, the Boston Pilgrims held a slim half-game lead. In a schedulemaker's dream, the Pilgrims faced the Highlanders that afternoon in the opener of a season-ending five-game series in the Big Apple. New York won on Friday to go a half-game up, but Boston shot back in front by sweeping a doubleheader the following afternoon. The season came down to a Sunday twinbill, with the Highlanders needing both games to win the flag.

In the opener, New York staked Chesbro to a 2-0 lead, but Boston tied the game in the seventh. It remained 2-2 in the ninth when Lou Criger singled and moved around to third on a sacrifice and a ground out. Chesbro then uncorked the most famous wild pitch in history as Criger scampered home with the pennant-clinching run. But Boston's thrilling victory proved somewhat empty. Fearing the Highlanders would win the pennant, McGraw and Brush had earlier refused to meet the AL victor in a championship match. Both claimed they still refused to recognize the AL, but many believed the real truth was they didn't want to risk their supremacy against another New York club.

-- David Nemec & Saul Wisnia

Baseball: More Than 150 Years

8th INNING

Stats: Most Valuable Player (NL)

1911: Frank Schulte (CHC) ... 1912: Larry Doyle (NYG) ... 1913: Jake Daubert (BRO) ... 1914: Johnny Evers (BSN) ... 1924: Dazzy Vance (BRO) ... 1925: Rogers Hornsby (STL) ... 1926: Bob O'Farrell (STL) ... 1927: Paul Waner (PIT) ... 1928: Jim Bottomley (STL) ... 1929: Rogers Hornsby (CHC) ... 1931: Frankie Frisch (STL) ... 1932: Chuck Klein (PHI) ... 1933: Carl Hubbell (NYG) ... 1934: Dizzy Dean (STL) ... 1935: Gabby Hartnett (CHC) ... 1936: Carl Hubbell (NYG) ... 1937: Joe Medwick (STL) ... 1938: Ernie Lombardi (CHC) ... 1939: Bucky Walters (CIN) ... 1940: Frank McCormick (CIN) ... 1941: Dolph Camilli (BRO) ... 1942: Mort Cooper (STL) ... 1943: Stan Musial (STL) ... 1944: Marty Marion (STL) ... 1945: Phil

Cavaretta (CHC) ... 1946: Stan Musial (STL) ... 1947: Bob Elliott (BSN) ... 1948: Stan Musial (STL) ... 1949: Jackie Robinson (BRO) ... 1950: Jim Konstanty (CIN) ... 1951: Roy Campanella (BRO) ... 1952: Hank Sauer (CHC) ... 1953: Roy Campanella (BRO) ... 1954: Willie Mays (NYG) ... 1955: Roy Campanella (BRO) ... 1956: Don Newcombe (BRO) ... 1957: Hank Aaron (MIL) ... 1958: Ernie Banks (CHC) ... 1959: Ernie Banks (CHC) ... 1960: Dick Groat (PIT) ... 1961: Frank Robinson (CIN) ... 1962: Maury Wills (LAD) ... 1963: Sandy Koufax (LAD) ... 1964: Ken Boyer (STL) ... 1965: Willie Mays (SFG) ... 1966: Roberto Clemente (PIT) ... 1967: Orlando Cepeda (SFG) ... 1968: Bob Gibson (STL) ... 1969: Willie McCovey (SFG) ... 1970: Johnny Bench (CIN) ... 1971: Joe Torre (STL) ... 1972: Johnny Bench (CIN) ... 1973: Pete Rose (CIN) ... 1974: Steve Garvey (LAD) ... 1975: Joe Morgan (CIN) ... 1976: Joe Morgan (CIN) ... 1977: George Foster (CIN) ... 1978: Dave Parker (PIT) ... 1979: Keith Hernandez (STL) & Willie Stargell (PIT) ... 1980: Mike Schmidt (PHI) ... 1981: Mike Schmidt (PHI) ... 1982: Dale Murphy (ATL) ... 1983: Dale Murphy (ATL) ... 1984: Ryne Sandberg (CHC) ... 1985: Willie McGee (STL) ... 1986: Mike Schmidt (PHI) ... 1987: Andre Dawson (CHC) ... 1988: Kirk Gibson (LAD) ... 1989: Kevin Mitchell (SFG) ... 1990: Barry Bonds (PIT) ... 1991: Terry Pendleton (ATL) ... 1992: Barry Bonds (PIT) ... 1993: Barry Bonds (SFG) ... 1994: Jeff Bagwell (HOU) ... 1995: Barry Larkin (CIN) ... 1996: Ken Caminiti (SDP) ... 1997: Larry Walker (COL) ... 1998: Sammy Sosa (CHC) ... 1999: Chipper Jones (ATL) ... 2000: Jeff Kent (SFG) ... 2001: Barry Bonds (SFG) ... 2002: Barry Bonds (SFG) ... 2003: Barry Bonds (SFG) ... 2004: Barry Bonds (SFG) ... 2005: Albert Pujols (STL) Cavaretta (CHC) ... 1946: Stan Musial (STL) ... 1947: Bob Elliott (BSN) ... 1948: Stan Musial (STL) ... 1949: Jackie Robinson (BRO) ... 1950: Jim Konstanty (CIN) ... 1951: Roy Campanella (BRO) ... 1952: Hank Sauer (CHC) ... 1953: Roy Campanella (BRO) ... 1954: Willie Mays (NYG) ... 1955: Roy Campanella (BRO) ... 1956: Don Newcombe (BRO) ... 1957: Hank Aaron (MIL) ... 1958: Ernie Banks (CHC) ... 1959: Ernie Banks (CHC) ... 1960: Dick Groat (PIT) ... 1961: Frank Robinson (CIN) ... 1962: Maury Wills (LAD) ... 1963: Sandy Koufax (LAD) ... 1964: Ken Boyer (STL) ... 1965: Willie Mays (SFG) ... 1966: Roberto Clemente (PIT) ... 1967: Orlando Cepeda (SFG) ... 1968: Bob Gibson (STL) ... 1969: Willie McCovey (SFG) ... 1970: Johnny Bench (CIN) ... 1971: Joe Torre (STL) ... 1972: Johnny Bench (CIN) ... 1973: Pete Rose (CIN) ... 1974: Steve Garvey (LAD) ... 1975: Joe Morgan (CIN) ... 1976: Joe Morgan (CIN) ... 1977: George Foster (CIN) ... 1978: Dave Parker (PIT) ... 1979: Keith Hernandez (STL) & Willie Stargell (PIT) ... 1980: Mike Schmidt (PHI) ... 1981: Mike Schmidt (PHI) ... 1982: Dale Murphy (ATL) ... 1983: Dale Murphy (ATL) ... 1984: Ryne Sandberg (CHC) ... 1985: Willie McGee (STL) ... 1986: Mike Schmidt (PHI) ... 1987: Andre Dawson (CHC) ... 1988: Kirk Gibson (LAD) ... 1989: Kevin Mitchell (SFG) ... 1990: Barry Bonds (PIT) ... 1991: Terry Pendleton (ATL) ... 1992: Barry Bonds (PIT) ... 1993: Barry Bonds (SFG) ... 1994: Jeff Bagwell (HOU) ... 1995: Barry Larkin (CIN) ... 1996: Ken Caminiti (SDP) ... 1997: Larry Walker (COL) ... 1998: Sammy Sosa (CHC) ... 1999: Chipper Jones (ATL) ... 2000: Jeff Kent (SFG) ... 2001: Barry Bonds (SFG) ... 2002: Barry Bonds (SFG) ... 2003: Barry Bonds (SFG) ... 2004: Barry Bonds (SFG) ... 2005: Albert Pujols (STL)IMAGE: Roy Campanella on the cover of a 1955 issue of TIME

9th INNING

Player Profile: Bo Belinsky

Full name: Robert Belinsky Full name: Robert BelinskyNickname:

Born: December 7, 1936 (New York, NY)

Died: November 23, 2001 (Las Vegas, NV)

ML Debut: April 18, 1962

Final Game: May 18, 1970

Bats: Left Throws: Left

6'2" 191

Played for Los Angeles Angels (1962-64), Philadelphia Phillies (1965-66), Houston Astros (1967), Pittsburgh Pirates (1969), Cincinnati Reds (1970)

[O]n and off the field, the most noted hurler of all on the 1962 [Los Angeles] Angels was southpaw Bo Belinsky.

Probably no major leaguer has received more publicity for doing less than the screwballer Belinsky. By the time he had finished an eight-year career that included lengthy stays in the minors and on the disabled list, he had won a mere 28 games, arriving at double figures only in his rookie year and even then losing more than winning. Just once, in 1964 when he was 9-8, did he stack up more victories than losses. In 1962, however, Belinsky burst on a stodgy baseball scene with a reputation as a womanizer, pool hustler, and all-around bon vivant, and promptly added value to all these pastimes by racking up his first five decisions; one of the wins was a May 5 no-hitter against Baltimore, the organization from which the Angels had drafted the lefty and that had rejected a bid from California to take him back after an unimpressive showing in spring training. Thanks in part to his media-intense surroundings in Los Angeles and in part to aging Hearst columnist Walter Winchell's doting on him as a perfect partner for doubledating actresses the newsman wanted to impress, Belinsky was soon as much of a regular feature in gossip columns as he was on sports pages. With no attempt to disguise his nocturnal roamings, he was linked at one time or another with Iran's Queen Soraya and actresses Ann-Margret, Connie Stevens, and Tina Louise. The lengthiest relationship of all was with actress Mamie Van Doren, whose regular presence at Dodger Stadium* in low-cut outfits out-Hollywooded the Hollywood atmosphere surrounding the Dodgers and did nothing to hurt the Angels gate. For a while, the team also tolerated increasing coverage being given to Belinsky's rowdy influence on other Angels, particularly pitching ace [Dean] Chance, who by his own admission rarely skipped the all-night parties, night club shows, and pool games that attracted his roommate.

The party started to peter out when, after going 6-1 in his first seven decisions, Belinsky hit a wild streak (he led the AL in walks in 1962) and went 4-10 for the rest of the year. {Manager Bill] Rigney, who had disliked the pitcher's style from the beginning and who had tried in vain to persuade [Fred] Haney to send him back to Baltimore during spring training, appeared to have more success when he urged the general manager to use Belinsky as bait in ongoing trade talks with Kansas City for reliever Dan Osinski. A's president Charlie Finley agreed to accept Belinsky as "a player to be named alter" after the season in exchange for Osinski. But then A's manager Hank Bauer, who was either very careless or very nimble about evading a problem he didn't want, let Belinsky know he was the player-to-be-named later. The pitcher, who had no desire to leave Los Angeles for Kansas City, waited until the team arrived in New York for a game against the Yankees and, assured of maximum media coverage, announced that he knew all about the deal between Haney and Finley and that he was going anwhere; moreover, he challenged both the commissioner's office and the AL to look into a situation where a player who was already traded might have been representing the league in the World Series. The ploy worked. Commissioner [Ford] Frick threw the hot potato to the American League, and AL president Joe Cronin passed it on to Finley and Haney behind a warning that everyone's interests might best be served by replacing Belinsky in the deal. An infuriated Haney persuaded the A's to accept lefty Ted Bowsfield as a substitute.

About the only members of the organization not ambivalent about Belinsky were Rigney, who didn't want him around, and Chance, who very much did. Haney and Autry, in particular, changed their minds whenever Rigney announced a new fine against the hurler for missing a curfew, then changed them back again whenever his appearance on the mound or in a newspaper photograph boosted gate receipts .... Then in late May, Rigney again appeared to have prevailed when Belinsky's 1-7 record (with an ERA approaching six) argued convincingly for a stay back in the minors. Because the Angels' chief farm club was in Hawaii, however, Belinsky had no problem accepting the demotion, to the point that he resisted a recall to Los Angeles in August. With tales of his Hawaiian adventures added to those in California, the southpaw actually received a $2,000 raise for the 1964 season despite an overall performance of 2-9, with a 5.75 ERA. To some degree, the incentive paid off because Belinsky responded with his only winning season. But the 1964 campaign also featured a punchup with Los Angeles Times sportswriter Braven Dyer, after which there was a perceptible change in the media coverage of Belinsky's antics. He was dealt to the Phillies over the winter for Rudy May and, under increasing drinking and arm problems, started wandering around the National League from Philadelphia to Houston to Pittsburgh to Cincinnati. After failing in an attempt to catch on with St. Louis in 1971, he called it quits.

--Dewey & Acocella

Total Ballclubs

*The Angels played in Dodger Stadium for four of their first five seasons as part of an agreement with Dodgers owner Walter O'Malley indemnifying the latter for giving up exclusive rights to the Los Angeles area. -- Ed.

IMAGE: Bo Belinsky with actress Mamie Van Doren.

EXTRA INNINGS

They Played the Game

Hughie Jennings

(1891-1909, 1912, 1918)

In 1896 this excitable, demonstrative Hall of Famer, nicknamed "Ee-Yah," became the last player in the NL to hit over .400 and yet fail to win the batting title. That year he set a record for the most RBIs (121) by a player who hit no home runs. He hit over .350 in '95, '96, and '97 and stole 359 bases during his playing career. He managed the Detroit Tigers from 1907-1920 and the New York Giants in 1924-25.

"Ee-Yah" BORN: 4.2.1869, Pittston, PA .311, 18, 840 Managerial record: 1184-995

Fernando Tatis

(1997-2003)

In a 23 April 1999 game between the Dodgers and the Cardinals, St. Louis third baseman Tatis hit two grand slam home runs in the same inning, something no player before him has ever done.

BORN: 1.1.1975, San Pedro de Macoris, PR .261, 90, 339

Joe Adcock

(1950-66)

Playing for the Braves in the 1950s, first baseman Adcock hit four homers in one game against the Dodgers (31 July 1954), and was the first batter to hit a ball completely over the left field grandstand at Ebbets Field. His "non-homer" ended Harvey Haddix's 12-inning perfect game on 26 May 1959; his hit was ruled a double when he ran past Hank Aaron on the bases. His career ratio for home runs -- one every 12.75 at-bats -- was the best in the league.

BORN 10.30.1927, Coushatta, LA .277, 336, 1122 All-Star 1960

George Bradley

(1875-88)

Talk about stamina -- Bradley pitched every inning of every one of the 64 games played by his team, the St. Louis Brown Stockings, in 1876. His record: 45 wins, 19 losses.

"Grin" BORN: 7.13.1852, Reading, PA 171-151, 2.42

Darrell Evans

(1969-89)

Evans became the first hitter with 40 or more home runs in a season in each league. In 1971 he hit 41 for the NL's Atlanta Braves, and in 1985 hit 40 for Detroit. In 1987 he set an ML record for players over 40 when he hit 34 homers.

BORN: 4.20.69, Pasadena, CA .248, 414, 1354 All-Star 1973, 1983

THIS MATERIAL IS REPRODUCED FOR NON-PROFIT EDUCATIONAL AND SCHOLARLY PURPOSES ONLY, WHICH COMPLIES WITH THE DOCTRINE OF FAIR USE AS EXPRESSED IN THE COPYRIGHT ACT OF 19 OCTOBER 1976, EFFECTIVE 1 JANUARY 1978 (TITLE 17 OF THE UNITED STATES CODE, PUBLIC LAW 94-553, 90 STAT. 2541.)

|